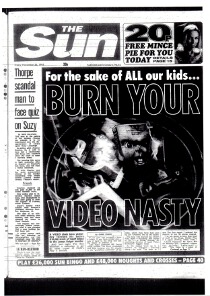

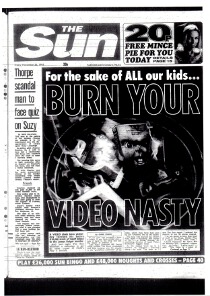

By the end of the 1950s, Britain had become the home of horror, with world-beating Gothic melodramas from Hammer Films, supplemented come the 60s with movies from rival studios like Amicus and Tigon. As the 70s progressed, however, British genre cinema fell victim to its own success, oversaturating the market with product, while systemic problems in the film industry began to bite. Brit horror took a further hammer blow in the 80s, when a tabloid-led moral panic triggered the draconian ‘Video Nasties’ legislation, effectively criminalising the distribution and possession of many genre films on the vital new home video format.

UK horror cinema then languished in the doldrums for decades, with few truly British horror films being made, and even fewer worth watching. Happily, the genre has subsequently enjoyed a creative and commercial renaissance in the UK in the 21st Century. For me the landmark movie was Neil Marshall’s minor masterpiece of 2002, DOG SOLDIERS. I went to the opening fully prepared to be disappointed by another homegrown failure, only to be delighted by a film that was witty, well-paced and actually pretty scary in parts.

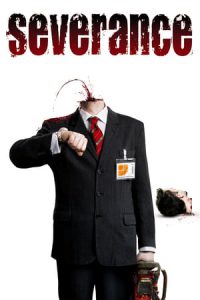

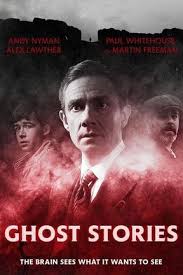

If future film scholars write a history of this 21st century British horror renaissance, there will undoubtedly be numerous index entries for the multi-talented Andy Nyman. While he hasn’t yet collaborated with Neil Marshall, Andy’s appeared in two horror films for the underrated director and screenwriter Christopher Smith (the 2006 gory satire of office politics SEVERANCE and the 2010 medieval folk horror nasty BLACK DEATH). He’s also enjoyed plum roles in some of the best small screen Brit horror mini-series, including Charlie Brooker’s zombie-BIG BROTHER mash-up DEAD SET, and Mark Gattis’s haunted manor anthology CROOKED HOUSE (both 2008).

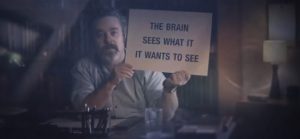

But Mr Nyman is a true renaissance man, having performed in numerous other theatre, film and TV productions, including providing voices for the popular MINIONS animated movie (2015) and appearing in the hit PEAKY BLINDERS TV series (2013). He’s also an accomplished magician, and has collaborated with the celebrated psychological illusionist Derren Brown, co-writing many of Brown’s award-winning magic specials, starting with the 2000-03 TV series MIND CONTROL. Nyman was originally expected to front the show, but deferred in order to concentrate on other projects.

But Mr Nyman is a true renaissance man, having performed in numerous other theatre, film and TV productions, including providing voices for the popular MINIONS animated movie (2015) and appearing in the hit PEAKY BLINDERS TV series (2013). He’s also an accomplished magician, and has collaborated with the celebrated psychological illusionist Derren Brown, co-writing many of Brown’s award-winning magic specials, starting with the 2000-03 TV series MIND CONTROL. Nyman was originally expected to front the show, but deferred in order to concentrate on other projects.

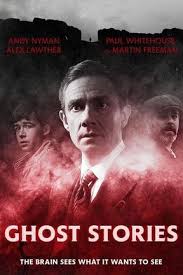

Projects like creating the 2010 stage play GHOST STORIES, co-written and co-directed with Jeremy Dyson, best known as the silent partner on the cult BBC black comedy series LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN (another key component in British horror’s 21st Century revival). Their theatrical chiller proved a big hit, breaking box office records, and running for over 1,000 performances, including shows in Moscow and Toronto. Nyman and Dyson decided to adapt their play to the big screen, with Andy now also taking the lead role of Professor Phillip Goodman, the arch-sceptic whose determination to debunk the supernatural leads him into nightmare realms his academic background had not prepared him for.

Projects like creating the 2010 stage play GHOST STORIES, co-written and co-directed with Jeremy Dyson, best known as the silent partner on the cult BBC black comedy series LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN (another key component in British horror’s 21st Century revival). Their theatrical chiller proved a big hit, breaking box office records, and running for over 1,000 performances, including shows in Moscow and Toronto. Nyman and Dyson decided to adapt their play to the big screen, with Andy now also taking the lead role of Professor Phillip Goodman, the arch-sceptic whose determination to debunk the supernatural leads him into nightmare realms his academic background had not prepared him for.

There are obvious autobiographical connections between Andy and the professor – they share a Jewish background and both have been involved in debunking psychic fraud. When I had an opportunity to talk to Andy recently, I wanted to unpick a few of the ideas behind the densely-layered film, which is a lot more thoughtful than many of the Hollywood haunted house films that have been popular in recent years. Some critics have compared Nyman’s GHOST STORIES (2017) to the gleefully ghoulish Amicus anthology films of the 1970s, and there’s something to that (in one of many in-jokes, a tin of cat food in the film is named after the Tigon studio). Yet in many respects, GHOST STORIES is more akin to the psychological dread of DEAD OF NIGHT, the 1945 anthology film that is arguably the first true classic of British horror cinema. So I began by trying to establish how Andy had become associated with the genre…

There are obvious autobiographical connections between Andy and the professor – they share a Jewish background and both have been involved in debunking psychic fraud. When I had an opportunity to talk to Andy recently, I wanted to unpick a few of the ideas behind the densely-layered film, which is a lot more thoughtful than many of the Hollywood haunted house films that have been popular in recent years. Some critics have compared Nyman’s GHOST STORIES (2017) to the gleefully ghoulish Amicus anthology films of the 1970s, and there’s something to that (in one of many in-jokes, a tin of cat food in the film is named after the Tigon studio). Yet in many respects, GHOST STORIES is more akin to the psychological dread of DEAD OF NIGHT, the 1945 anthology film that is arguably the first true classic of British horror cinema. So I began by trying to establish how Andy had become associated with the genre…

GB: To go back to the start of your screen career, I didn’t realise you were in the original 1989 TV version of THE WOMAN IN BLACK…

AN: It was my first TV role. It’s been amazing happenstance really that I’ve ended up in a few of these things. It wasn’t like I wanted to be a horror actor – it just happened. I’ve done so much varied and interesting work, and it just so happened that that was there, and then DEAD SET happened and then SEVERANCE. I’ve always played extreme roles – I enjoy playing extreme characters whether it’s Patrick in DEAD SET or Churchill in PEAKY BLINDERS. There’s something about playing larger than life people that I enjoy.

I was trying to thinking of a unifying factor in some of the roles you played, in horror at least. I came up with the word ‘hapless’. Just like Sean Bean supposedly always dies in everything he’s in, your characters seem to get the shitty end of the stick a lot…

I was trying to thinking of a unifying factor in some of the roles you played, in horror at least. I came up with the word ‘hapless’. Just like Sean Bean supposedly always dies in everything he’s in, your characters seem to get the shitty end of the stick a lot…

AN: That’s a fun observation, but that’s actually not really the case. It’s only been a few of my roles. There’s Gordon in SEVERANCE. In DEATH AT A FUNERAL the character that I play literally gets the shitty end of things. But then you look at Patrick in DEAD SET and it’s the polar opposite of that. I mean, yes he ends up getting ripped apart, but he’s a fighter, not a weak man. I think extremity’s the thing that’s always appealed to me. If I’ve just played a character who’s hapless, the next part I play won’t be, because I like always doing different things.

GB: I think what I was trying to get at is that your characters always seem to end up being punished. Obviously in DEAD SET your character is a villain – he’s a bad man – everyone’s rooting for the zombies to tear him apart. But the scene where he craps in a bin takes it further somehow. I don’t know why, but it is a particularly memorable scene.

AN: Yes, that’s right it is. I don’t know really. I just like taking roles that interest me and they often involve extreme scenes like that, which was just a joy as an actor. I’ve never been an actor who has played roles that are charming – where he wanders into the room and everyone swoons – though there’ll be characters that need charm to achieve an end.

GB: Getting onto GHOST STORIES, the punishment your character goes through seems wholly disproportionate to what he’s done.

AN: That’s a really interesting point. And I’ll tell you about that because we’ve wrestled with that a lot, me and Jeremy. When we were writing the film, an early version of it went to a producer, and we ended up parting company with them. One of the things these producers really felt, was that it was too brutal, that they wanted conclusion that was slightly neater and slightly more comfortable, because it does feel so disproportionate. So we went down that route and we rewrote it, and after about three versions of that we realised this is not our thing anymore. So we went back and looked at the play, and what’s interesting about having the play is that you already have a product with a version that has worked and worked very successfully, so you can analyse the thing. What is it that worked about that, that isn’t working about this? We realised one of the things that’s very key is that the punishment is disproportionate. It’s biblical. It’s blood and thunder, that says if you sin – even if that is a sin of omission – you will be punished. You can’t bleat about that. You can’t complain that it’s too harsh. You wronged. And there is a consequence to that. It is harsh for sure, and it’s bleak, and not terribly nice. But what’s interesting within that, is at times it seems that we live in a world where actions often don’t have consequences. You look at how politicians behave and think how is this happening? Or why am I paying more tax than Google? Where is the right and wrong here? Where is the simple humanity and morality? And so there’s something very interesting to us about the unapologetic biblical nature of your demons. You’ll pay you pay for your crimes, pay for your sins.

GB: The film’s called GHOST STORIES. But you could argue that there are few if any traditional ghosts in it. It’s almost begging the question what is a ghost? If you look at the work of the most famous ghost story writer of all time, M.R. James, surprisingly few of his tales feature classic ghosts. Do you believe in ghosts in any shape or form? And what do you mean by ghosts in this film?

GB: The film’s called GHOST STORIES. But you could argue that there are few if any traditional ghosts in it. It’s almost begging the question what is a ghost? If you look at the work of the most famous ghost story writer of all time, M.R. James, surprisingly few of his tales feature classic ghosts. Do you believe in ghosts in any shape or form? And what do you mean by ghosts in this film?

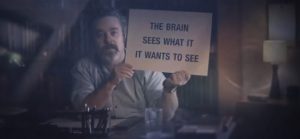

AN: I don’t believe in ghosts. What do we mean by ghosts? Well, Martin Freeman’s character Mike Priddle identifies it when he says that every action we’ve ever done, ever word we’ve ever uttered, has a consequence – a little ghost of itself, a trace. He says to my character Goodman “That’s true isn’t it?” And that is true. Every single conversation you have, every single thing you do or say, has a consequence that can be both positive and negative. The way you treat people, the way you conduct your life, the emails you send, the tweets you make – every single thing that you do has a ripple effect, and can’t really begin to imagine where that ends. So what’s scary is… Both Jeremy and I aren’t religious, but we’re both quite spiritual and think that there’s certainly a lot of power in religious teachings and in religion itself. One of those things that is a scary consequence is that it’s really easy to live in a secular society where you’re not answering to a higher power. This is Goodman’s thing. You’re not answering to anyone, it’s great – let yourself off the fucking hook mate! Do whatever you want – there’s only the here and now. But that’s not true. It’s not true if you’ve got kids. It’s not true if you’re in a relationship. Every time you roll your eyes when you partner says something. Every time you huff and puff. It has an impact. It has an impact on you, on their health, on my health, on everything, let alone how they then conduct themselves in their life and how that goes on. Well there’s a big difference between that and following a teaching, believing in a higher power – which I don’t – believing in that. And the danger with where we are – Jeremy and I believe – is that you end up throwing the baby out with the bathwater. You end up saying “There is no God – it’s all bullshit – it’s not true. I believe in Dawkins – Dawkins is right. Religion’s all just a convenient set of nonsensical rules.” And what you end up doing is just throwing away all of that wisdom and power and truth and construct that makes living life – which is hard, and throws up challenges you can never imagine – harder.

GB: That leads onto one of the things I was wanting to talk about briefly – about how I was surprised that GHOST STORIES felt almost anti-rationalist. The film opens up with this fraudulent psychic – and this scene links to a lot of your other work with Derren Brown – but from thereon in your character is sort of crucified by his own scepticism.

GB: That leads onto one of the things I was wanting to talk about briefly – about how I was surprised that GHOST STORIES felt almost anti-rationalist. The film opens up with this fraudulent psychic – and this scene links to a lot of your other work with Derren Brown – but from thereon in your character is sort of crucified by his own scepticism.

AN: The film is anti-rationalist. It is. And we could sort of skirt around that, but it is. Equally I am a rationalist. But that’s what’s interesting about working in the way we do, is it does throw up challenges that make me think about the way I think or believe or not believe, which I also wrestle with. I was never religious. But I like being Jewish. I like the trappings of it and I like the philosophies of it, and I grew up going to the synagogue, being bar mitzvahed and all that stuff. As I got older, I started working with Derren Brown, and then my dad died, and I thought fuck all that shit. I started looking at it all, started pulling it apart, and decided it’s all nonsense. Sure enough though, the older I get the more I wrestle with it a bit more. Because it isn’t nonsense. The notion of God may be nonsense. Our notion of God as an omniscient higher power may be nonsense. But you know there is a God. Look at the NHS. That is the most brilliant embodiment of God on earth, where everybody in our country pays into something, gives of themselves to help whoever. You go to a space where people are not paid well, where miracles happen. Literally miracles happen.

GB: I seem to recall a politician described the NHS as the closest the UK gets to a true religion…

AN: Which is why where we are right now is so painful. It’s profound where we are at the moment politically. It isn’t just about whether we want immigrants or not. It’s profoundly disturbing to think that selfishness and greed can beat selflessness. It’s just staggering and it feels irreligious – it feels sacrilegious – to neglect this incredible thing that’s still so relatively young, but is amazing. Something that has literally worked miracles in my immediate family. I’m talking about me my wife my two kids. Let alone what it’s done for your life or for our parents’ lives. It has worked miracles for everyone. So that to me is an example of an interesting crossover. You can just say that that’s not God. But the question then is what is God? If you don’t believe in that, in the notion of giving of yourself, and kindness, and treating others well, and all of those things that are easy to just throw away. To think that’s not true – it’s rubbish. But it isn’t rubbish. It isn’t. It’s massive, massive, massive stuff.

GB: I think there’s a danger here of spinning off into a deep theological debate about here. This is a three hour conversation and I know our time is limited. So I’d like to finish on an aspect of horror history that still fascinates many genre fans – the Video Nasties panic of the 1980s. It’s interesting how many of the films they banned weren’t much good, but because kids were watching these fuzzy, third generation copies on video, they took on this almost totemic status…

GB: I think there’s a danger here of spinning off into a deep theological debate about here. This is a three hour conversation and I know our time is limited. So I’d like to finish on an aspect of horror history that still fascinates many genre fans – the Video Nasties panic of the 1980s. It’s interesting how many of the films they banned weren’t much good, but because kids were watching these fuzzy, third generation copies on video, they took on this almost totemic status…

AN: What goes hand in hand with that is you’re also having an almost mythological experience because you’re watching these things where the graininess tells you that it has been watched a thousand times. It’s a shared experience strangely. Also it’s playing the brilliant part of adding another layer of intrigue and mystery onto the experience. What am I looking at through this fog and fuzz? Trying to get to the bottom of it. It was so exciting that stuff. It’s so important to have that kind of thing.

For more on Andy’s many endeavours, check out his website here.

With special thanks to the lovely Natalie Boyd, for arranging this interview.