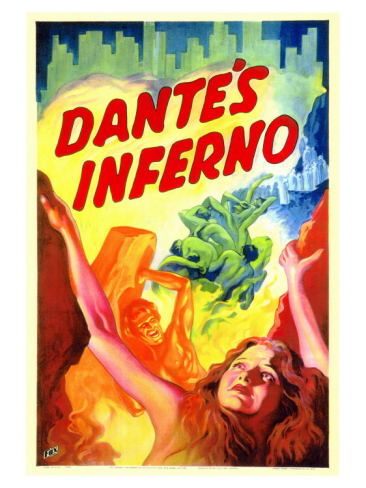

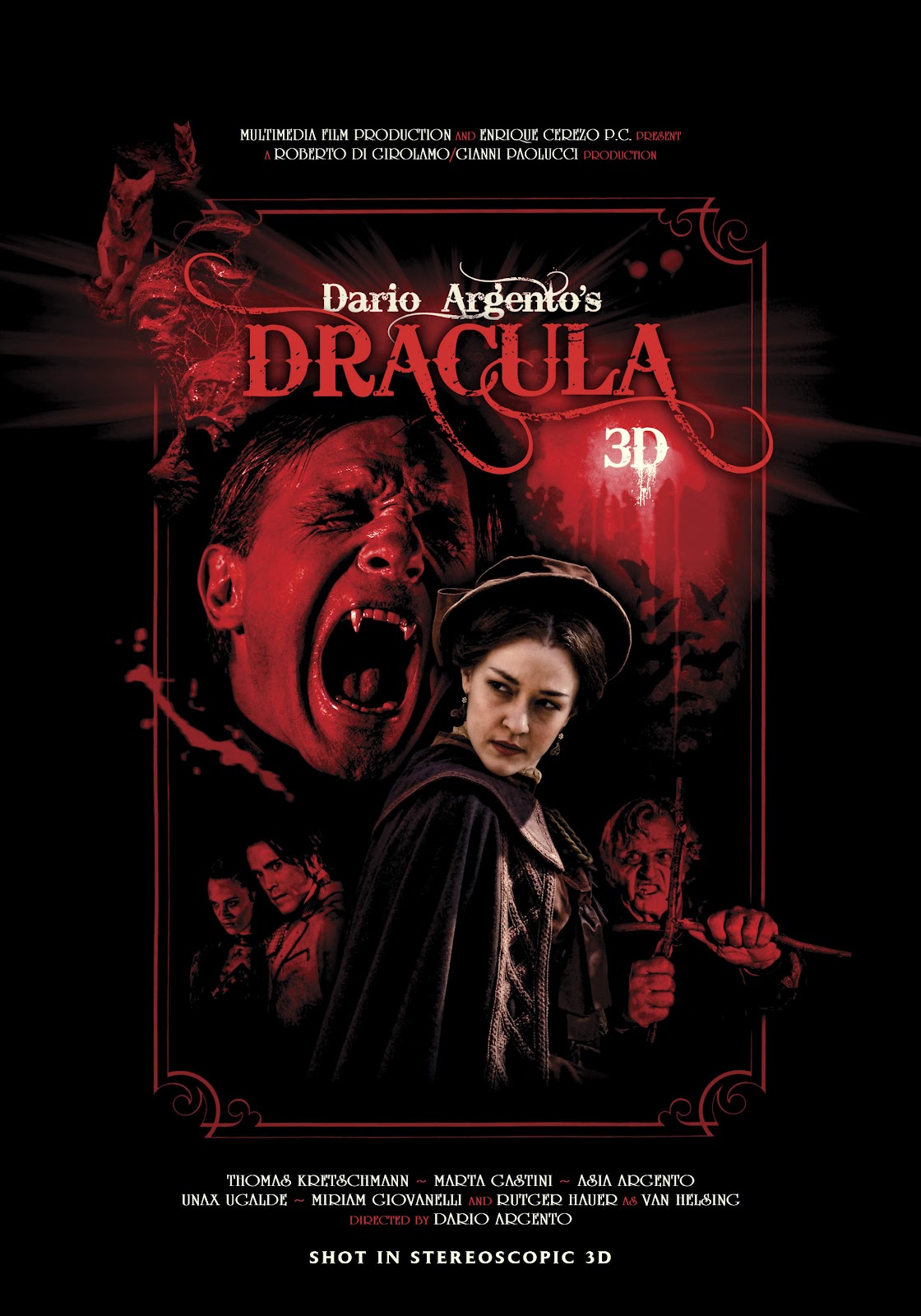

Among the loot I brought back after sacking Rome recently was the latest movie by local filmmaker Dario Argento. I mentioned the movie in a recent essay on this very site in less-than-glowing terms, so thought the least I could do was actually watch the film before joining the herd in dismissing it as a disaster, sight unseen. For the benefit of those unfamiliar with the work of Mr Argento, he’s long enjoyed a reputation as perhaps Italy’s most stylish and audacious horror director, most famously for his delirious 1977 masterpiece ‘Suspiria’. In recent years, however, that reputation has plummeted courtesy of a succession of highly disappointing flicks, leaving many dedicated fans now hoping Dario won’t make another film, just as fervently as they once wished he would.

His most recent effort is ‘Dracula 3D’, which premiered at Cannes over a year ago, where, it was widely and comprehensively panned by the critics. (The review in ‘Variety’, which dismissed it as ‘a near-two-hour joke that ought to have been funnier’, was pretty typical.) Under this salvo of bad notices the film appeared to retreat off the radar, confirming suspicions for many that this wasn’t the film to rescue Argento’s reputation. But I couldn’t help but be curious, and when I saw a copy on DVD in Profondo Rosso, Dario’s shop in Rome, I snapped it up. Could it really be as bad as rumour had suggested? After all – to adopt my seldom-worn optimist’s hat – many of the director’s early classics were condemned by conventional critics upon initial release, awaiting discovery by more discerning eyes among genre devotees…

First off, it’s worth noting that my copy wasn’t in 3D, so I can’t comment on that aspect of the production. So let’s refer to it as ‘Dario’s Dracula’ – or ‘DD’ – from hereon in rather than ‘Dracula 3D’. Secondly, there will be minor spoilers in the following paragraphs, for which I apologise. But, frankly, if you’re approaching this film hoping for a complex, clever plot full of cunning twists, there’ll be tears before bedtime. There again, plotting and characterisation have never been Argento’s strong suit even in his best pictures, and ‘DD”s certainly no exception. Many elements appear plucked from other vampire flicks and cast haphazardly into the script on a whim, with little narrative tension to speak of. To be fair, ‘DD’ is clearly the product of folk familiar with horror cinema (though there’s little evidence of familiarity with the original novel) and genre veterans can play a game of ‘spot the reference’ in order to enliven proceedings.

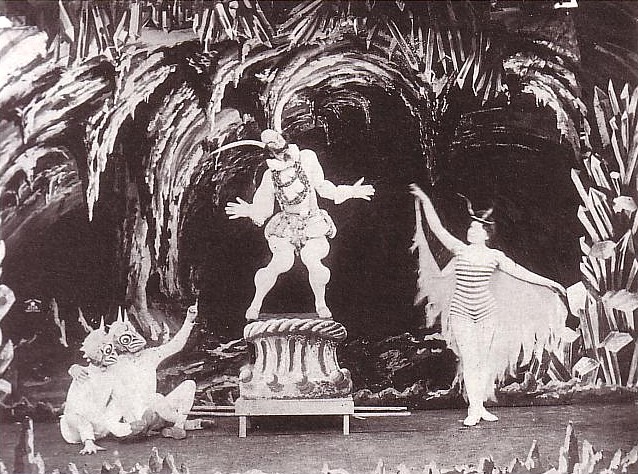

So, for example, Jonathan Harker (somewhat anachronistically sporting a black ponytail) is a librarian, employed by the Count to sort out his book collection. Chalk one up for the 1957 Hammer version. The hackneyed plot device of having Harker’s wife Mina as the reincarnation of the Count’s lost love is plundered from the Francis Ford Coppola blockbuster version of 1992 (or, just maybe, the 1974 Jack Palance TV movie). I like to think that an early scene featuring some stuffed animals is in tribute to Jess Franco’s characteristically crackpot, low budget ‘Count Dracula’ (1970), which features a stuffed animal attack as one of its least special effects. I suspect Dario was aiming for something that captured the lush Gothic atmosphere of the Hammer and Coppola hits. He’s ended up with something rather closer to Franco’s steaming, chaotic stew of gore and sleaze in period garb.

There is the requisite dose of flesh and blood we’ve come to expect from classic Euro-horror – the first gratuitous sex scene hits just after five minutes in – and most of the actresses disrobe at some point in the proceedings. (Including Dario’s daughter, Asia, who seems to get naked in most of her father’s films these days – which is either refreshingly liberated or slightly weird – don’t ask me which.) Similarly there’s plenty of bloodshed, though too much of it’s achieved using clumsy CGI, of which more anon. Suffice to say, many of the killings might make you wince, but not often for the right reasons. Another issue here, is that there’s probably a little too much sex and violence for this to reach a mainstream audience, yet far too little to impress the kind of horror fan who’ll forgive a myriad of cinematic shortcomings as long as you throw enough voluptuous flesh and viscera at the screen. While in Italian horror’s 1980s heyday, films by Argento and friends were being banned for being excessively brutal and perverse, ‘DD’ looks tame, even quaint and comical, next to the barbed cutting-edge of the modern post-torture porn competition.

As I’ve already suggested, the CGI doesn’t help. I’m not among the radical puritans who condemn its use under all circumstances. Used with skill in the right situations, CGI represents a potent tool in the filmmaker’s arsenal. Yet the CGI in ‘DD’ mostly just looks cheap and dated – some of it wouldn’t be out of place in a bargain bin computer game – though there are occasions where it works. Similarly there are a number of wolf attacks in the film. Shooting day for night is a money-saving technique most of us are familiar with from low budget horror, and largely inclined to forgive. For the wolf attacks in ‘DD’, however, Argento is either trying to be quirky by staging the scenes in blazing sunlight, or he’s not bothered to even pretend its night-time for reasons of cost, time or energy. Who knows?…

One of the more original – and frequently commented upon – aspects of ‘DD’ is Argento’s unorthodox use of more unfamiliar animals in his freewheeling take on the vampire myth. According to the original novel, Dracula ‘can command all the meaner things, the rat, and the owl, and the bat, the moth, and the fox, and the wolf, he can grow and become small…’ While most adaptations confine themselves to allowing the Count to become a bat or wolf, Dario goes one further, making his Dracula transform into several unexpected critters, most infamously, a preying mantis! If I’m honest, I liked these offbeat elements of inventiveness, and would’ve welcomed more. I don’t think ‘DD’ was ever going to work as a straight Gothic that could stand up against the big budget Hollywood competition, so a retreat further into sinister surrealism might well have worked in its favour.

Performances are probably best described as competent, particularly given the dodgy dialogue they often have to chew over. ‘DD’s Renfield is a lumbering thug who reminded me a bit too much of Father Jack from the priestly sit-com ‘Father Ted’. Rutger Hauer half-heartedly channels the Anthony Hopkins Van Helsing from the Coppola ‘Dracula’, while Thomas Kretschmann as his nemesis the Count delivers a dignified, if unspectacular performance. To be fair, he’s following in the footsteps of actors who occupied the character so effectively as to struggle to escape the role, such as Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee, who were always going to be tough acts to follow. While the script obviously demands an undead antihero, crackling with demonic, erotic menace, Kretschmann’s Count has the gravitas but not the charisma to pull it off. There’s more of the vindictive bureaucrat than the cursed aristocrat about this Dracula – he feels more likely to audit the shit out of your accounts than steal your immortal soul.

Completing the ensemble is a soundtrack courtesy of Argento veteran Claudio Simonetti. It’s a curiously old-fashioned affair, most reminiscent of spooky TV shows of the 1960s – say ‘The Twilight Zone’ or even ‘Dark Shadows’ – complete with theremin. It contributes a cartoonish tone to proceedings – ‘Scooby Doo’ with tits maybe – while the accompanying video single ‘Kiss Me Dracula’ wouldn’t look out of place in ‘Eurovision’. Little in ‘DD will please Argento purists or mainstream horror fans, and I’ve spent most of this piece pouring scorn upon the film. But I can’t escape the fact that I had a blast watching it. There are moments that suggest the dark genius behind Dario’s best work, and even at its direst, ‘DD’ is infinitely more fun than the teen-obsessed dreck and found-footage bilge that passes for horror in most multiplexes these days. Misconceived, frequently daft, often slapdash, for sure, but I grinned throughout the whole silly exercise. Maybe it’s time to stop praying for another ‘Suspiria’, and to just crack open another beer and enjoy the show…

This immediately felt like yet another of my rants that demanded a flurry of apologies, exemptions and provisos to preface it. I do use the term ‘fan’ in a positive sense on a regular basis, often interchangeably with terms like ‘aficionado’ or ‘devotee’. So, for example, if I say an event is run ‘by fans, for fans’, I’m expressing approval, in contrast to more cynical festivals and such where financial profit’s the motivating factor. (It’s an indication of the perceived marketing value of being seen as a fan-focused event that so many film and music events portray themselves as such, when they’re quite clearly purely commercial endeavours.) There is, of course, much to be said for folk who are enthusiastic about and dedicated to the art or entertainment they enjoy, but I think there’s a little more to fandom than that.

This immediately felt like yet another of my rants that demanded a flurry of apologies, exemptions and provisos to preface it. I do use the term ‘fan’ in a positive sense on a regular basis, often interchangeably with terms like ‘aficionado’ or ‘devotee’. So, for example, if I say an event is run ‘by fans, for fans’, I’m expressing approval, in contrast to more cynical festivals and such where financial profit’s the motivating factor. (It’s an indication of the perceived marketing value of being seen as a fan-focused event that so many film and music events portray themselves as such, when they’re quite clearly purely commercial endeavours.) There is, of course, much to be said for folk who are enthusiastic about and dedicated to the art or entertainment they enjoy, but I think there’s a little more to fandom than that.