Recently, the nice people at Lionsgate asked me in my capacity as a devotee of all things devilish to contribute to the launch of the new Silent Hill sequel. I was happy to oblige with a few interviews on the subject of Hollywood’s depictions of Hell, plus an essay on the topic. Several fine film sites published the essay, though in its truncated form, focusing on more recent film – based on the sound philosophy that attention spans on the Internet can be somewhat short, and the rather more dubious assumption that nobody’s interested in anything that happened before they were born.

Recently, the nice people at Lionsgate asked me in my capacity as a devotee of all things devilish to contribute to the launch of the new Silent Hill sequel. I was happy to oblige with a few interviews on the subject of Hollywood’s depictions of Hell, plus an essay on the topic. Several fine film sites published the essay, though in its truncated form, focusing on more recent film – based on the sound philosophy that attention spans on the Internet can be somewhat short, and the rather more dubious assumption that nobody’s interested in anything that happened before they were born.

(Any potential clients might care to note that, whenever appropriate, I put essays together in a ‘modular’ form, making it easy for paragraphs to be extracted without damaging the sense or flow of the piece, allowing for maximum adaptability. Plug done.)

Incidentally, Silent Hill: Revelation is great fun. While it’s unlikely to excite fervent disciples of French New Wave cinema, or indeed Fellini aficionados, it looks great – sharing that same eerily epic aesthetic as the original – moves at a cracking pace, retains its commendable fidelity to the spirit of the original games, and most importantly, has some truly marvelous monsters (such as our rather splendid friend at the head of this post). Top beer and popcorn horror with all the requisite jump scares and creepy twists. Meanwhile, I thought some of you might enjoy this first section of the essay which hasn’t yet seen the light of day, covering depictions of the Underworld in early cinema. Hope you like it…

HOLLYWOOD GOES TO HELL

By Gavin Baddeley

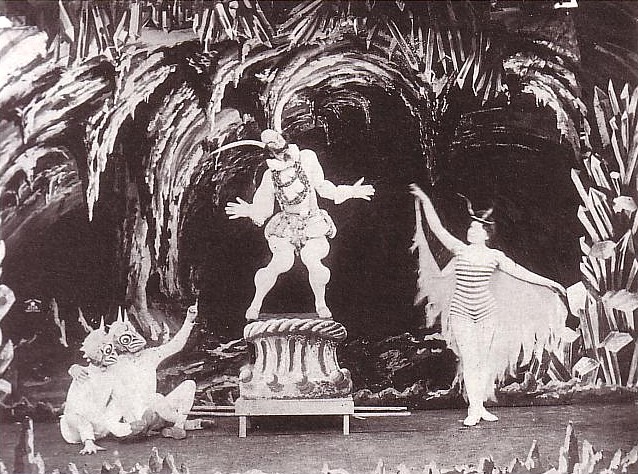

Starting in 1896, the Parisian illusionist and special effects pioneer Georges Méliès made well over 500 films – many of them only a few minutes long – mostly to showcase the camera trickery he was developing with the new medium. The Frenchman saw cinema as a tool to amaze and enchant audiences, filming the fantastic, frequently taking on the role of the Devil himself in front of the camera. Inevitably, many of his films haven’t survived, but two from 1903 are still with us in the form of Faust aux enfers (usually translated as The Damnation of Faust) and Cakewalk Infernal, making these perhaps cinema’s earliest surviving forays into the Underworld.

The story of Doctor Faust, the supposedly real German sorcerer who sold his soul to a devil named Mephistopheles, has inspired numerous works of art, music and literature, including several short films by Méliès. In The Damnation of Faust, we follow the doomed Doctor to Hell, which is full of sulphurous flames, monsters, devils and – somewhat incongruously – ballet dancers. Cakewalk Infernal introduces us to yet more damned dancers. This time devotees of the cakewalk, a goofy dance invented by slaves on American plantations to mock their swaggering masters, which subsequently became an international sensation. As this suggests, though Méliès is often cited as a horror movie pioneer, and there are macabre elements in his films, the tone is more often whimsical and fantastic rather than horrific or morbid.

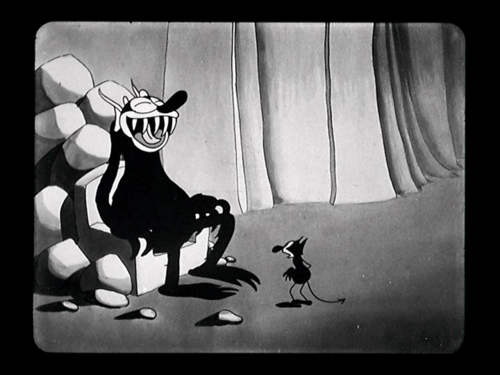

Another cinematic pioneer who took a light-hearted look at Hell was Walt Disney, suggesting our great grandparents were less uptight than we might suppose. In the 1929 animated short Hell’s Bells, one of Disney’s ‘Silly Symphonies’, spindly demons cavort through Hades, a cavernous realm inhabited by bats and serpents. The tone is surprisingly dark, not least when Satan gleefully feeds his imps to his three-headed dog Cerberus. Six years later, the studio released Pluto’s Judgement Day, in which Mickey Mouse’s dog Pluto (also the name of the Roman god of the Underworld incidentally) chases a kitten, and then dreams he’s lured into Hell. This Hades, however, is a Hellish court staffed by demonic cats who try, and then find the cartoon dog guilty of his sins. While both shorts are obviously played for laughs, it’s difficult to imagine Disney animating such hot topics in the studio’s later years.

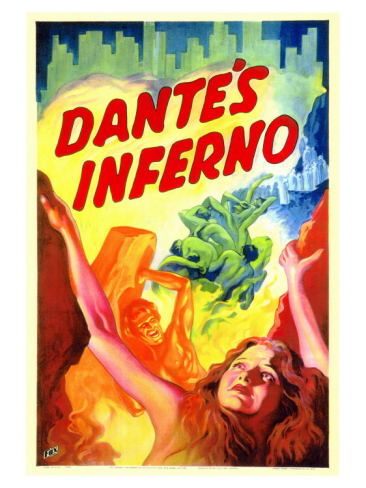

Of course, some early filmmakers did take the prospect of everlasting damnation more seriously. The first ever feature film from Italy, home of Catholicism, was an adaptation of the epic 14th Century Italian poem Inferno by Dante Alighieri. (It’s worth noting here that of the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy – detailing journeys to Hell, Purgatory and Heaven – it’s the first that enjoys by far the most interest, reflecting the aspects of the traditional Afterlife that fascinate us most.) The 1911 film effectively brings to life the engravings of the Victorian artist Gustave Doré, the best-known illustrations of Dante’s classic depiction of a journey into Hell. While modern viewers might be most shocked to note that the film follows Dante’s original poem and puts Mohammed in Hell, a century back it was the nudity that upset some viewers.

Despite – or more likely because of – this L’Inferno proved an international success, and, in an early example of a time-honoured Hollywood tradition, the film was duly ripped off in the US. The pirate in question was the infamous director and producer Dwain Esper, the man responsible for such zero budget dreck as Reefer Madness and How to Undress in Front of Your Husband. Esper randomly spliced scenes from L’Inferno into his dodgy 1936 oddity Hell-A-Vision. Nudity had become officially taboo in Hollywood after the imposition of the Hays Code of censorship rules in 1934, giving Esper’s threadbare outlaw production the added allure of the forbidden. Oddly enough, this wasn’t the only example an American director using Dante’s Inferno as an excuse to include some titillation in their depictions of Hell.

The 1924 film Dante’s Inferno concerns a slum landlord who’s so wicked that a demon arrives to drag him down to a Netherworld inspired by the 14th Century poem. It’s the climax of the film, built on huge sets and, as it precedes the 1934 code, a surprising number of those writhing in the flames or being whipped, are doing so without a stitch on. The 1935 remake features Spencer Tracy as an immoral fairground owner whose shady character earns him a trip through the fiery depths of Hades. As this Dante’s Inferno debuted post-Hays Code, while there’s plenty of chains and sweating flesh, voluminous wigs come in handy to cover the modesty of the damned. From a purely moral standpoint, the trouble is that these Netherworlds seem more exciting than terrifying somehow – certainly the scenes they appear in are highlights in a pair of otherwise rather dull films.

Despite easy assumptions about the piety of yesteryear, by the 1940s, Hades was – if anything – being treated with even greater irreverence in Hollywood. In the whimsical 1943 fantasy Heaven Can Wait, a spoiled socialite tries desperately to prove he lived a sinful life in order to get into Hell, which seems to resemble an exclusive gentleman’s country club. The same year saw the release of a big screen adaptation of the witty, all-black Broadway jazz musical Cabin in the Sky, in which the Underworld is a swinging juke joint, and the forces of Heaven and Hell decked out in dapper, old-fashioned military uniforms. In Angel On My Shoulder (1946), Old Nick mischievously swaps the souls of a virtuous judge with a loutish hoodlum – with Hades depicted as resembling an American penitentiary, complete with trustees and a warden.

It’s almost as if, in an age which witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust and Hiroshima, the idea of a fiery pit staffed by guys in red suits wielding pitchforks had become redundant to the point of camp. That’s certainly the way it comes across in The Devil with Hitler, a 1942 propaganda piece where Hell is like a corporation, with its demonic board threatening to sack Satan for failing to be as wicked as the Fuhrer. The traditional terrors of Hellfire seem to have cut even less ice in Hollywood in the Fifties, as the Cold War unleashed fears of nuclear apocalypse and communist subversion. A typical quasi-scientific – even atomic – treatment of the Afterlife is the star-studded 1957 flop The Story of Mankind in which the ‘High Tribunal of the Great Court of Outer Space’ is convened because humanity has developed a ‘Super H-Bomb’ capable of wiping out the entire human race. For the prosecution, arguing that man should be allowed to destroy himself is Old Scratch – played by horror legend Vincent Price – while Ronald Colman (in his final role) argues for our preservation as the Spirit of Man.

The most interesting interpretations of Hell in the Sixties came from beyond Hollywood. The Devil’s Messenger (1961) was cobbled together from a Swedish TV series entitled 13 Demon Street, and features a wraparound story in which Satan (played by Lon ‘Wolfman’ Chaney Junior) tries to recruit souls to join him in Hell. With echoes of The Story of Mankind, the Devil’s ultimate plan involves destroying humanity with a nuclear bomb. In Ingmar Bergman’s characteristically melancholy Swedish 1960 comedy The Devil’s Eye, Don Juan – history’s greatest lover – is tormented in a highly theatrical Hell, by having to constantly repeat his greatest seductions without ever consummating any of them. Jigoku (1960, nominally remade in 1979 and 1999) from Japan offered a Buddhist interpretation of Hell, which is a stopping-off point in the cycle of reincarnation to which we condemn ourselves. Unusually, at a time when Japanese horror cinema was usually painterly, poetic and haunting, Jigoku tried to shock with its cheap and deliberately nasty depictions of the suffering of the damned.

If you found this little essay diverting, you might like to read the second part, which brings us up to date with matters infernal and cinematic. The following fine film websites have all been kind enough to publish it: Midnight Review, the Incredibly Strange Movie blog, Movie Ramblings, Horror Talk, Pissed Off Geek, and Total: Spec.