I seem to have spent much of my writing career wrestling with popular myths and fashionable falsehoods. For want of a better term, let’s call these ‘revelatoids’. So, what’s a revelatoid? Allow to me to offer as an example an old favourite, which I’ve been encountering anew with depressing frequency during recent research. It concerns witches, specifically, the idea that historical witchcraft, as manifest in European history of the late Middle Ages and Early Modern eras, had nothing to do with the Devil. You’ll find this confidently stated in magazine articles, in books, and on radio and TV documentaries. Indeed, repeated often enough with sufficient conviction that folk could now be forgiven for believing it to be true. Unless, of course, you’re familiar with the original sources…

Bar a flimsy fistful of interesting exceptions, every significant document from what we might call ‘the Golden Age of European Witchcraft’ – say 1300-1700 – makes prominent mention of Satan in some unholy shape or form. Now you could argue that most such documentary evidence is compromised by bias – overwhelmingly the work of fervently Christian authors, frequently quoting from confessions extracted under extreme duress. But, quite frankly, that’s pretty much all we’ve got that’s worth the paper its printed on. The other ‘evidence’ you’ll find on offer almost invariably turns out to be wayward wishful thinking, concocted in more recent times to some modern agenda, a.k.a. ‘shit some bozo made up’.

Bar a flimsy fistful of interesting exceptions, every significant document from what we might call ‘the Golden Age of European Witchcraft’ – say 1300-1700 – makes prominent mention of Satan in some unholy shape or form. Now you could argue that most such documentary evidence is compromised by bias – overwhelmingly the work of fervently Christian authors, frequently quoting from confessions extracted under extreme duress. But, quite frankly, that’s pretty much all we’ve got that’s worth the paper its printed on. The other ‘evidence’ you’ll find on offer almost invariably turns out to be wayward wishful thinking, concocted in more recent times to some modern agenda, a.k.a. ‘shit some bozo made up’.

Open season on re-inventing witchcraft began in the 1920s when an eminent Egyptologist named Margaret Murray, while on hiatus from unwrapping mummies, stumbled upon a theory that connected witchcraft with a pre-Christian fertility cult. Witches actually revered Mother Nature, but were persecuted as Satanists and forced underground by fanatical Christian clergyman, who in their ignorance mistook the witches’ horned hunting god for that other notorious horny character from Hell. It was a fascinating idea with but one fatal flaw. It was almost certainly total bullshit. Respect for Margaret’s good name as an Egyptologist ensured her theory enjoyed a brief respite of academic respectability, before its tender underbelly of implausibility was exposed, and the scholastic hounds of history tore Murray’s pet theory limb from limb.

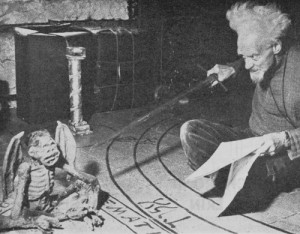

Understandably, under such pressure, the pet theory slipped the leash and became increasingly wild, embracing such madcap notions as a secret royal conspiracy of human sacrifice and a race of literal little people, dubbed ‘fairies’ by us dull ordinary folk. By this point the only serious attention Margaret’s pet theory was enjoying in academic circles was hostile – used as target practice by mean-spirited historians looking for an easy hypothesis to shoot down for fun or profit. The retired Egyptologist’s knight-in-shining-armour came in the eccentric shape of an ex-civil servant named Gerald Gardner, a well-travelled amateur anthropologist with an interest in historical weaponry and exotic religions.

By recruiting a few occult enthusiasts of his acquaintance, and combining some of his own peccadilloes – notably nudism and a little light S&M – with Murray’s theories, Gerald came up with a practical programme, a creed he dubbed ‘Wicca’. While sceptics might observe that his coven seemed more like a Home Counties swingers club than a pre-Christian sect, for Gardner and friends, the aura of witchcraft served both to justify their al fresco frolics and add a deliciously unholy frisson of wickedness to proceedings. Crucially, however, Murray’s theories allowed these newly minted ‘witches’ a get-out-clause whereby if challenged, they could piously observe that witchcraft had nothing to do with the Devil, hence anyone criticising them was taking the side of the sadistic bigots of the Church who persecuted, tortured and murdered so many innocents in centuries past.

Distinctly dodgy claims to roots stretching back millennia notwithstanding, Wicca was born in the years following World War Two. It was given a welcome shot-in-the-arm in 1951 with the repeal of the Witchcraft Act of 1735, which Gardner claimed finally allowed him to be open about his beliefs. Gerald was being disingenuous at best. The Act of 1735 wasn’t about persecuting witches as dangerous heretics, but aimed at stopping con artists from defrauding the gullible with claims of magical powers. The law that replaced it, the Fraudulent Mediums Act, was much the same, altered only slightly to allow Spiritualist churches exemption from prosecution for fraud. Both acts treat witches as fraudsters rather than sorcerers, and would’ve made no practical difference to Gerald’s gaggle of occult-inclined naturists, unless they were fleecing people. But it made for good press, an ideal opportunity to exploit the wave of ill-informed media interest stirred up by the repeal of the Act.

By the time Gardner died in 1964 a fertile new field of potential converts were emerging among the flower children of the nascent hippie movement. The naturism and risqué rituals dovetailed neatly with the hippie ‘free love’ ethos, while evidence that many traditional witches’ potions contained psychoactive ingredients encouraged mystically minded acidheads to see kindred spirits in the covens. Another self-styled high priest – or indeed King of the Witches no less – soon leapt nimbly into Gerald’s still-warm sandals, in the shape of one Alex Sanders, a fellow Brit who proved adept at exploiting the widespread growing interest in all things occult burgeoning in the Sixties. While the witch-finders of yesteryear rode out equipped with thumbscrews and pricking needles, their 20th Century counterparts were armed with telephoto lenses, notebooks and a lascivious leer.

For, much as Sanders liked to maintain that there was no erotic element to his naked ceremonies, few really bought the line. Least of all the tabloid and colour supplement editors who printed acres of newsprint covering the supposed witchcraft revival, illustrated by copious photographs of attractive young witches, frolicking au naturel for the edification of the reading public. Alex’s nubile wife Maxine later observed that she doubtless had the most photographed bum in England. Repeating the suspect story that these were the inheritors of an ancient pre-Christian religion seemed a small price to pay – and useful justification – for getting away with printing such nakedly prurient pictures in ‘family’ newspapers. The other increasingly familiar mantra of Wiccan dogma was the ‘fact’ that witchcraft had nothing to do with the Devil, and that anything bad associated with the occult was all the fault of elusive – and frankly largely imaginary – Satanists.

Curiously, the Sixties also saw the term ‘witch-hunt’ enter widespread popular usage as a metaphorical term for any draconian persecution of innocent scapegoats. The McCarthyite ‘Red Scare’ of 1950-56 was increasingly described as a witch-hunt in retrospect (thanks, in part to Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible which used the Salem Witch trials on 1692-3 as a metaphor for McCarthyism). Serious historical scholarship on witchcraft was starting to examine the phenomenon as a manifestation of the horrors of murderous scapegoating, which had reached an appalling apex in the 20th Century with the Nazi Holocaust. Were the witch-hunts Early Modern Europe’s equivalent? Wiccans liked to think so, as it reinforced their self-image as a long-oppressed minority, persecuted for centuries and now deserving of sympathy and special treatment. At least it would if their creed bore any real resemblance to historical witchcraft. More pertinently perhaps, if the building historical consensus was correct, and the witches executed in days gone by were simply victims of delusional persecution, was there ever truly any witchcraft tradition to adhere to anyway?…

Such questions went largely unanswered – and indeed unasked – within Wiccan ranks however, as our latter-day witches began to warm to the role of oppressed martyrs. A new phrase began to be bandied about in the Seventies – ‘the Burning Times’ – referring to the movement’s supposed times of trial in days gone by. Accompanying these buzzwords came fresh claims and jargon. Nine million women had died during the Burning Times, a tragedy that qualified as ‘Gendercide’, the murderous suppression of the feminine power manifest in witchcraft by the patriarchy. Inevitably, perhaps, little of this would pass muster with serious scholars. The number of victims quoted is absurd – reliable estimates suggest well under 1% of the figure so often quoted – of whom most where hanged not burnt, and while the majority were female (maybe 75%) many of those who died were men. But we can’t let historical research get in the way of spiritual truth now can we?…

The idea of witchcraft as a feminist force actually first emerged in parallel to Wicca, when a New York group emerged in 1968 calling themselves W.I.T.C.H.. It stood for ‘Women’s International Terrorism Conspiracy from Hell’ and consisted of radical feminists who struck out at what they perceived as misogynist targets with acts of satirical revolutionary street theatre while dressed as Halloween witches, a process that they described as ‘hexing’ or ‘zaps’. The victims of hexing included Wall Street, male-dominated revolutionary movements and bridal fairs, before W.I.T.C.H. fizzled out in 1970. Meanwhile Wicca was also embracing a revolution, as many began rejecting the leadership of ‘Kings’ like Gardner and Sanders – who seemed increasingly inappropriate icons for such a traditionally feminine practise as witchcraft. Similarly, the Horned God was frequently given his marching orders in favour of placing a Mother Goddess centre stage, with some covens even adopting a ‘ladies only’ policy, a version sometimes styled as Dianic Wicca.

The idea of witchcraft as a feminist force actually first emerged in parallel to Wicca, when a New York group emerged in 1968 calling themselves W.I.T.C.H.. It stood for ‘Women’s International Terrorism Conspiracy from Hell’ and consisted of radical feminists who struck out at what they perceived as misogynist targets with acts of satirical revolutionary street theatre while dressed as Halloween witches, a process that they described as ‘hexing’ or ‘zaps’. The victims of hexing included Wall Street, male-dominated revolutionary movements and bridal fairs, before W.I.T.C.H. fizzled out in 1970. Meanwhile Wicca was also embracing a revolution, as many began rejecting the leadership of ‘Kings’ like Gardner and Sanders – who seemed increasingly inappropriate icons for such a traditionally feminine practise as witchcraft. Similarly, the Horned God was frequently given his marching orders in favour of placing a Mother Goddess centre stage, with some covens even adopting a ‘ladies only’ policy, a version sometimes styled as Dianic Wicca.

The Great Rite – ritual sex, frequently employed by male coven leaders to initiate pretty recruits – became yesterday’s news, replaced at first by a symbolic version (thrusting a knife into a cup) before largely being abandoned altogether. Other risqué practises, once integral to Wicca, such as flagellation and nudity, faded into symbolic versions before often being abandoned altogether. Witchcraft – at least in this version – was losing its frisson of wickedness, its alluring aura of sin washed away and replaced by green awareness and liberal gender politics. Ironically, one is tempted to observe, the very engine of its invention in the mid-1900s – the exercise of the libido in an exotic, interesting milieu – was removed, leaving behind only the tenuous ideological window-dressing that once justified it. The supernatural swingers had stopped swinging.

The Great Rite – ritual sex, frequently employed by male coven leaders to initiate pretty recruits – became yesterday’s news, replaced at first by a symbolic version (thrusting a knife into a cup) before largely being abandoned altogether. Other risqué practises, once integral to Wicca, such as flagellation and nudity, faded into symbolic versions before often being abandoned altogether. Witchcraft – at least in this version – was losing its frisson of wickedness, its alluring aura of sin washed away and replaced by green awareness and liberal gender politics. Ironically, one is tempted to observe, the very engine of its invention in the mid-1900s – the exercise of the libido in an exotic, interesting milieu – was removed, leaving behind only the tenuous ideological window-dressing that once justified it. The supernatural swingers had stopped swinging.

At this stage in proceedings, those persistent readers with the endurance to reach this far in this rambling essay might feel entitled to wonder if we’re any closer to a point. Will we ever find out what a ‘revelatoid’ might be? What, indeed, has it to do with a notably spiteful dissection of the less edifying aspects of the history of Wicca? For, to be fair, many 21st Century Wiccans probably wouldn’t disagree with many of the observations made here, even if they might take issue with the mean-spirited tone in which they were made. Among the better-informed adherents there’s a willingness to concede that historical scholarship is against them, to accept that their form of witchcraft is a largely modern invention. But – what the Hell – Wicca works for them, so why change it? To be honest, even I’d struggle to argue with that. So why waste all these words washing Wicca’s dirty laundry?

Well, it’s because I’m sick of hearing the revelatoid that witchcraft has nothing to do with the Devil, which Wicca’s ultimately responsible for propagating, even if it’s spread by numerous sundry numbskulls these days. I’m now long overdue explaining my term, so here goes. A revelatoid is a particular species of factoid. For those unfamiliar with this word, it refers to a frequently repeated falsehood. A classic example is the notion that most people only use 10% of their brain, something that is only true of the kind of people who repeat this silly statistic. A revelatoid is a surprising revelation repeated specifically to try and establish its author as an expert in a specific field, and like a factoid is actually firmly rooted in 24-carat-bullshit but repeated often enough to enjoy some specious legitimacy. So, faux occult experts frequently try and establish their credentials with the shock disclosure that witchcraft historically has nothing to do with the Devil.

As I suggested at the start of this rambling address, my career seems to have centred on confronting revelatoids. So, for example, after my first book on Satanism (when I first began to be irritated by the dubious legacy of Wiccan wisdom) I penned a cultural dissection of the singer Marilyn Manson. Ask most people to categorise Manson’s music, and I suspect many might still identify his work as Gothic rock. Suggest that to most self-respecting Goths, however, and they’ll react with a mixture of dismay and disdain. Because, as every authentic Goth knows, Marilyn Manson is the very definition of not being a Goth. Indeed, expressing contempt for the vocalist is the secret password that establishes the speaker as clued-in on the subculture, unlike the poor fools taken in by the ignorant mass media. The only thing is, this is horseshit. Gender-bending, wildly coloured hair, platform boots and an obsession with Tim Burton, David Bowie and Bauhaus: So Marilyn Manson’s a fucking reggae singer?…

As I suggested at the start of this rambling address, my career seems to have centred on confronting revelatoids. So, for example, after my first book on Satanism (when I first began to be irritated by the dubious legacy of Wiccan wisdom) I penned a cultural dissection of the singer Marilyn Manson. Ask most people to categorise Manson’s music, and I suspect many might still identify his work as Gothic rock. Suggest that to most self-respecting Goths, however, and they’ll react with a mixture of dismay and disdain. Because, as every authentic Goth knows, Marilyn Manson is the very definition of not being a Goth. Indeed, expressing contempt for the vocalist is the secret password that establishes the speaker as clued-in on the subculture, unlike the poor fools taken in by the ignorant mass media. The only thing is, this is horseshit. Gender-bending, wildly coloured hair, platform boots and an obsession with Tim Burton, David Bowie and Bauhaus: So Marilyn Manson’s a fucking reggae singer?…

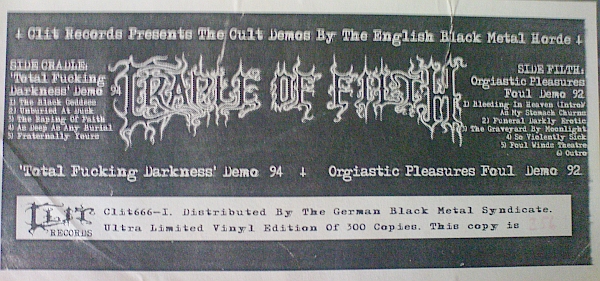

There’s a very similar scenario regarding Cradle of Filth, who were the subject of another of my books a few years back. The imaginary initiation into the make-believe secret black metal circle involves fervently disavowing Cradle before sagely intoning that they’re not proper black metal, and that only a prize fool would mistake them for such. Yet, as much as black metal is a specific style of music, the British band were playing it and touring with fellow black metal bands when many of the pompous tools making such statements were just an unhealthy glimmer in Jimmy Savile’s eye. Cradle themselves have wisely shrugged and abandoned such battles long ago as a waste of time, but I can’t help feeling mildly irritated on their behalf. If only because I’ve been listening to black metal for even longer, and don’t take kindly to being lectured by the hoards of bandwagon-jumping bell-ends.

There’s a very similar scenario regarding Cradle of Filth, who were the subject of another of my books a few years back. The imaginary initiation into the make-believe secret black metal circle involves fervently disavowing Cradle before sagely intoning that they’re not proper black metal, and that only a prize fool would mistake them for such. Yet, as much as black metal is a specific style of music, the British band were playing it and touring with fellow black metal bands when many of the pompous tools making such statements were just an unhealthy glimmer in Jimmy Savile’s eye. Cradle themselves have wisely shrugged and abandoned such battles long ago as a waste of time, but I can’t help feeling mildly irritated on their behalf. If only because I’ve been listening to black metal for even longer, and don’t take kindly to being lectured by the hoards of bandwagon-jumping bell-ends.

This meandering missive is already too long by half, and as I plan to elaborate on my charges of bell-endery in black metal (and possibly also the depressing sport of Gothic one-upmanship) at a later date, I should probably wrap up and shut up. I’m under no delusion that ‘revelatoid’ will catch on and endure as a term, in fact I sincerely hope it doesn’t. In part because it sounds too much like a shitty Dr Who monster, and partially because if I’m entirely honest, I rather like myths, and what I’ve been describing has largely involved the evolution of modern mythologies. But I don’t like it when myths limit their subject or slowly drain it of mystery or danger, which is what has happened with revelatoids like the Wiccan Devil denial. Plus, the really wonderful thing about history is that it’s almost invariably far more interesting and shocking than the shit bozos make up…