I’ll be hosting a special event this Halloween at the Grade II listed Chapel of Rest in York’s picturesque Victorian cemetery. Entitled Nightmares in Black and White, and running between 2-5pm, I’ll be taking people on an illustrated tour through the twisted roots of horror cinema. Informal, but informative, and suitable for both curious newcomers and seasoned horror fiends alike, we’ll lift the (coffin) lid on the stories behind the classic Hollywood monsters we’ve come to know and love so well. The local paper ran a two page article on the event, which you can read here. If you’re interested, do please send me a message via this site, or the event’s Facebook page here

.

.

Being a Count in Whitby

With due apologies for the short notice, I will be attending the Bram Stoker Film Festival in Whitby tomorrow, the 22nd of October, where I shall be delivering a talk at 2.30pm. Entitled, somewhat impudently, Who are You Calling a Count?, I shall be exploring the links – or lack thereof – between the fictional Count Dracula and his 15th Century historical namesake Vlad the Impaler. The Festival lasts throughout the weekend, and alongside horror film premieres, also features a vampire ball, and performances by the likes of Goth rock gods Fields of the Nephilim. For further info, click here. Maybe see some of you there…

With due apologies for the short notice, I will be attending the Bram Stoker Film Festival in Whitby tomorrow, the 22nd of October, where I shall be delivering a talk at 2.30pm. Entitled, somewhat impudently, Who are You Calling a Count?, I shall be exploring the links – or lack thereof – between the fictional Count Dracula and his 15th Century historical namesake Vlad the Impaler. The Festival lasts throughout the weekend, and alongside horror film premieres, also features a vampire ball, and performances by the likes of Goth rock gods Fields of the Nephilim. For further info, click here. Maybe see some of you there…

Satan Goes Live with a Bang!

Little did I know, ten years ago, when I agreed to appear on a heavy metal documentary for a Canadian production company I’d never heard of, that I was becoming involved with an outfit that would change the way the world saw the music I’d grown up with. The resultant feature documentary, Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey, garnered awards and plaudits worldwide, establishing the Canadians, Banger Films, as the definitive documentarians of music’s most disreputable genre. They’re now taking that status to the next level, launching a dedicated metal channel.

Even more excitingly, on a personal level, they’re also unleashing a new feature documentary that takes them beyond the realms of music, to a topic dear to my black little heart. The feature is entitled Satan Lives…

‘Satan. Lucifer. Fallen Angel. The Devil. He has many names but strikes a singular emotion in billions of people: fear. From Biblical times to modern day, Satan has been portrayed as the worst evil known to man and is undoubtedly the greatest villain of all time. And yet, what do we really know about Him?

‘Satan. Lucifer. Fallen Angel. The Devil. He has many names but strikes a singular emotion in billions of people: fear. From Biblical times to modern day, Satan has been portrayed as the worst evil known to man and is undoubtedly the greatest villain of all time. And yet, what do we really know about Him?

‘Satan Lives will explore the role of the Devil in the modern age. It will trace His transformation from fallen angel to demonic beast to charismatic charlatan, showing how popular culture (from Milton’s Paradise Lost to The Exorcist to South Park) has influenced the public’s perception of the Devil’s presence on Earth. Featuring in-depth interviews with horror icons like John Carpenter, Linda Blair, Stephen King, Mike Mignola and Guillermo del Toro and musicians Bruce Dickinson, Jimmy Page, Rob Zombie and Marilyn Manson.

‘The documentary delves deep into questions of faith and the psychology of fear, travelling across North America, England and Europe to witness exorcism rites, examine psychiatric testing and reveal the scientific and supernatural forces behind Satan’s power today. Satan is about the power of fear and the nature of evil. It explores the story of the ultimate agent provocateur and reveals that perhaps Satan isn’t what we should be most afraid of at all.’

Between you and me, somebody else some of you may also recognise making an appearance. More info presently…

Panic on the Streets of London

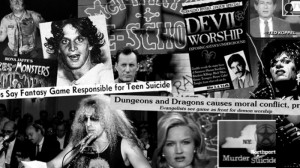

On October 8th, I’m pleased and proud to announce that I’ll be co-hosting an event for the acclaimed Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies, being held at the wonderfully atmospheric Horse Hospital in Blooomsbury, London. The night celebrates the release of the book Satanic Panic: Pop Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, which features a chapter by me on the crusade against Dungeons and Dragonsby Evangelical Christian campaigners. On stage with me will be author David Flint, discussing his researches into ‘the strange case of Genesis P-Orridge’, and Satanic Panic editor and Miskatonic founder Kier-La Janisse, who will be providing context for the evening. Meanwhile, I’ll be holding forth on bullshit fatigue, comparing and contrasting authentic occultism, fictional sorcery, and the fabricated magic described by Christian crackpots, before speculating on just what motivated all of these Satanic conspiracy theorists to fantasise for Jesus. Find further details and booking info here.

On October 8th, I’m pleased and proud to announce that I’ll be co-hosting an event for the acclaimed Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies, being held at the wonderfully atmospheric Horse Hospital in Blooomsbury, London. The night celebrates the release of the book Satanic Panic: Pop Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, which features a chapter by me on the crusade against Dungeons and Dragonsby Evangelical Christian campaigners. On stage with me will be author David Flint, discussing his researches into ‘the strange case of Genesis P-Orridge’, and Satanic Panic editor and Miskatonic founder Kier-La Janisse, who will be providing context for the evening. Meanwhile, I’ll be holding forth on bullshit fatigue, comparing and contrasting authentic occultism, fictional sorcery, and the fabricated magic described by Christian crackpots, before speculating on just what motivated all of these Satanic conspiracy theorists to fantasise for Jesus. Find further details and booking info here.

Lost, Unquenchable Hammer Dracula has Risen from the Grave!

With the growing number of horror festivals springing up all over the UK, organisers increasingly have to pull off something a bit special in order to lure in the fans. Mayhem in Nottingham certainly caught my attention when they announced plans to revive a lost Hammer Dracula script by having it read live on stage. This is particularly appropriate in the year we lost Christopher Lee, the brilliant actor most associated with the Count (somewhat to Lee’s dismay), and who Hammer planned would don the cloak had the production gone ahead.

With the growing number of horror festivals springing up all over the UK, organisers increasingly have to pull off something a bit special in order to lure in the fans. Mayhem in Nottingham certainly caught my attention when they announced plans to revive a lost Hammer Dracula script by having it read live on stage. This is particularly appropriate in the year we lost Christopher Lee, the brilliant actor most associated with the Count (somewhat to Lee’s dismay), and who Hammer planned would don the cloak had the production gone ahead.

To head the reading Mayhem have secured the services of Jonathan Rigby. An astute choice, as he’s not only among the foremost scholars of Gothic cinema, but an acclaimed actor in his own right. “The idea came about, as far as I’m aware, when it was realised that the Hammer archive at De Montfort University holds a number of unproduced scripts,” Jonathan told me. “[The script we are staging] is The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula and was written as the follow-up to Scars of Dracula. Anthony Hinds delivered his first draft in September 1970. Hammer had a contractual obligation to give Warner Bros first refusal on its Dracula pictures during this period, so EMI’s distribution of Scars… caused considerable friction.

“The Hammer/Warner Bros programme was supposed to get back on track with The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula, a story conceived by Hinds as a way for Warner to spend a large amount of rupees frozen in its Indian account (and thus appease them in the wake of the Scars… debacle). However, the success of Count Yorga, Vampire prompted Warner Bros to ask Hammer if it could attempt something similar, so in 1971 the production of what became Dracula AD 1972 took precedence. This was followed by The Satanic Rites of Dracula, which also had a modern-day setting. The India script was still being worked on – presumably because the situation with Warners’ frozen rupees had yet to be resolved – and was now going by the slightly altered title The Insatiable Thirst of Dracula.”

“The Hammer/Warner Bros programme was supposed to get back on track with The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula, a story conceived by Hinds as a way for Warner to spend a large amount of rupees frozen in its Indian account (and thus appease them in the wake of the Scars… debacle). However, the success of Count Yorga, Vampire prompted Warner Bros to ask Hammer if it could attempt something similar, so in 1971 the production of what became Dracula AD 1972 took precedence. This was followed by The Satanic Rites of Dracula, which also had a modern-day setting. The India script was still being worked on – presumably because the situation with Warners’ frozen rupees had yet to be resolved – and was now going by the slightly altered title The Insatiable Thirst of Dracula.”

“Once again, a gimmick took precedence, as in 1973 Hammer produced The Legend of 7 Golden Vampires for Warner as a way of cashing in on the craze for kung fu films,” adds Jonathan. “By this time the Indian story had been radically overhauled by Don Houghton and Chris Wicking as Kali – Devil Bride of Dracula. This was offered to Warner as a follow-up to 7 Golden Vampires…, but by this time the distributor had lost interest. Hammer abandoned the idea of shooting a film in India and instead concentrated its efforts on producing a film about Vlad the Impaler, based on Brian Hayles’ 1974 radio play Lord Dracula.”

After such a tortuous history, might it have been a good thing that viewers were spared another Hammer Dracula? Being blunt, is The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula actually any good? Jonathan’s confident that the script suggests the potential for a classic Hammer vampire chiller: “It’s set in the 1930s and is certainly more epic than Hammer were used to. There’s a major train journey complete with teeming termini at either end (a bit like Horror Express), a colossal Indian carnival scene with hundreds and hundreds of extras required (and a very nice death for a vampire-conniving Maharajah), hordes of devil worshippers a la The Kiss of the Vampire and The Devil Rides Out, a Black Hole of Calcutta-style pit in which Dracula’s female victims are dumped half-drained, a car chase between a rickety Morris tourer and the Maharajah’s coffin-bearing Rolls-Royce, and an apocalyptic ending in the ‘evil is propagated’ style that was fashionable (though not so much at Hammer) in the early 70s.”

Reading the script inevitably led a Hammer expert like Jonathan to envisage what The Unquenchable Thirst of Dracula might have looked like had it actually been filmed: “It’s very easy to spot the lines that Christopher Lee would have refused to speak! Joanna Lumley or Judy Geeson would have been good casting for the heroine at the time (as in Psycho, she’s searching for her vanished sister), and there are plenty of great roles for Indian actors, obviously. There’s also a dance sequence reminiscent of the sitar scene in The Reptile. Tony Hinds was stationed in India during the war and this experience fed not only into The Reptile but also The Ghoul. Unquenchable…, however, is actually set in India and thus takes fuller advantage of his local knowledge.”

The Mayhem Festival’s decision to stage the script live is a bold, imaginative one. It’s also perhaps the only way to recreate the inimitable style that made Christopher Lee and his films with Hammer so unique. You cannot go back in time to recreate the era, so why not employ the theatre of the imagination to conjure this Gothic masterpiece that never was? “Hammer’s Dracula endures through a combination of factors, chiefly the definitive potency of Christopher Lee’s performances and the beautifully upholstered Victorian-Edwardian milieu in which Hammer placed him,” concludes Jonathan. “I must say I’m looking forward to bringing this script to life; it’s a forgotten link in the Hammer chain and I’m sure it will fascinate all horror fans.”

The Mayhem Festival’s decision to stage the script live is a bold, imaginative one. It’s also perhaps the only way to recreate the inimitable style that made Christopher Lee and his films with Hammer so unique. You cannot go back in time to recreate the era, so why not employ the theatre of the imagination to conjure this Gothic masterpiece that never was? “Hammer’s Dracula endures through a combination of factors, chiefly the definitive potency of Christopher Lee’s performances and the beautifully upholstered Victorian-Edwardian milieu in which Hammer placed him,” concludes Jonathan. “I must say I’m looking forward to bringing this script to life; it’s a forgotten link in the Hammer chain and I’m sure it will fascinate all horror fans.”

Mayhem Horror Festival takes place at the Broadway Cinema in Nottingham between the 15th-18th of October. For further details click here.

You Shall Go to the Ball!

Autumn is shaping up to be a very busy one for me, with a wide variety of speaking engagements, seminars to teach and suchlike coming up in the next few months. I’ll post relevant details here closer to the time. For now, the first such outing is a signing I’ll be conducting at the Black Rose Ball here in York on Saturday, September 19th. An annual Gothic Masquerade in aid of the St Leonard’s Hospice, held at the outrageously elegant De Grey Rooms, the event’s established itself as a highlight in England’s dark culture calendar. A dress code is in place, so break out your finest Gothic plumage (masks are available on the door for a modest charge). If you fancy making a weekend of it, proceedings open the preceding night with performances by the popular Goth bands Dyonisis and Pretentious Moi? at the Fulford Arms.

Autumn is shaping up to be a very busy one for me, with a wide variety of speaking engagements, seminars to teach and suchlike coming up in the next few months. I’ll post relevant details here closer to the time. For now, the first such outing is a signing I’ll be conducting at the Black Rose Ball here in York on Saturday, September 19th. An annual Gothic Masquerade in aid of the St Leonard’s Hospice, held at the outrageously elegant De Grey Rooms, the event’s established itself as a highlight in England’s dark culture calendar. A dress code is in place, so break out your finest Gothic plumage (masks are available on the door for a modest charge). If you fancy making a weekend of it, proceedings open the preceding night with performances by the popular Goth bands Dyonisis and Pretentious Moi? at the Fulford Arms.

I can be found signing a selection of my books between 9-10pm at the De Grey Rooms on Saturday. Titles will be available to buy, though do feel free to bring anything you already own to be signed, or indeed just drop by for a chat. Liquor libations always gratefully received. For further details on the Black Rose Ball, click here. Hope to see some of you there!

(Photo by Chris Jones www.christopherjones.photography )

The Lost Industrial Chapter…

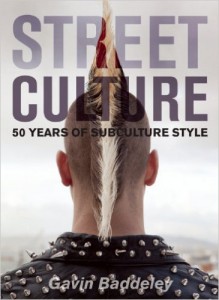

My new book, Street Culture should be hitting the streets soon. Like all of my books, there were compromises and editorial decisions taken during its composition. In order to fit the format my publisher liked, we had to cut some material. A few chapters were truncated. Others were assimilated into earlier chapters. For example, I originally had a chapter on the Scooter Boys, Soulies and Mod Revivalists that followed in the wake of the first wave of Mod, but who were sufficiently different to qualify as a new species. Sadly, space meant condensing them into a postscript in the Mod chapter.

My new book, Street Culture should be hitting the streets soon. Like all of my books, there were compromises and editorial decisions taken during its composition. In order to fit the format my publisher liked, we had to cut some material. A few chapters were truncated. Others were assimilated into earlier chapters. For example, I originally had a chapter on the Scooter Boys, Soulies and Mod Revivalists that followed in the wake of the first wave of Mod, but who were sufficiently different to qualify as a new species. Sadly, space meant condensing them into a postscript in the Mod chapter.

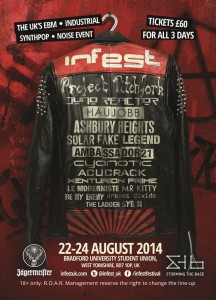

A couple of chapters pretty much disappeared in their entirety. Among these was the one on the Industrial subculture. This was a shame as, while I understood my publisher’s reasoning that they weren’t very well known, this also qualifies as an argument to keep them in. Certainly, in the 90s, industrial music and the accompanying aesthetic carved a significant place for itself in the no-man’s-land between Punk, Goth, Metal and Rave, having a notable impact on the scenes it touched upon. Anyhow, rather than waste the chapter, I thought I’d share it here. Please bear in mind that this is raw, unedited text, so likely contains numerous typos and mistakes. I hope you enjoy it anyway.

As with everything on this site. It’s (c) Gavin Baddeley. Do share, but show respect and professionalism and retain appropriate credits, links and suchlike please.

INDUSTRIALISTS & RIVET-HEADS

By many accounts, the Industrial movement is largely the result of a misunderstanding. The term was its origins with the American experimental musician and controversialist Monte Cazazza, who suggested the slogan ‘Industrial Music for Industrial People’ for the Industrial Records label, founded in the UK in 1976. The use of the term industrial in this context had several implications. In part it was an arch comment on the idea that a creative discipline like music could be an ‘industry’. In part it reflected the idea that, now most people laboured in factories rather than tilling fields, a new form of music was necessary that would address this profound change, something wholly different from Rock. Above all it was a provocative, eye-catching moniker for art designed to break down barriers. By the Eighties, Industrial was being re-interpreted as simply referring to any music made predominantly with electronic or mechanical equipment, which wasn’t what the originators had in mind at all.

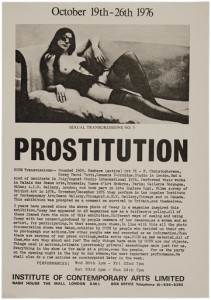

It’s perhaps significant that the Industrial label was founded in London at the height of the Punk explosion, caught up in the same initial frenzy of press outrage. Both movements had roots in the UK’s art schools. While Punk used fashion as a springboard to national notoriety via Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex boutique on the King’s Road, Industrial’s more low profile rise to infamy took place within the art world. Coum Transmission was an avant-garde art collective formed in 1969, with Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Megson) and Cosey Fanni Tutti (Christine Newby) at its core. They specialised in confrontational displays featuring everything from sadomasochism and blasphemy to fireworks and live sex acts. When the prestigious ICA gallery – keen for controversy – booked them to put on a show in the autumn of 1976, the group decided to give them more controversy than they could handle. Now bored with the insular art world, this would be the Coum Transmission’s swansong, an event they entitled ‘Prostitution’.

It’s perhaps significant that the Industrial label was founded in London at the height of the Punk explosion, caught up in the same initial frenzy of press outrage. Both movements had roots in the UK’s art schools. While Punk used fashion as a springboard to national notoriety via Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex boutique on the King’s Road, Industrial’s more low profile rise to infamy took place within the art world. Coum Transmission was an avant-garde art collective formed in 1969, with Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Megson) and Cosey Fanni Tutti (Christine Newby) at its core. They specialised in confrontational displays featuring everything from sadomasochism and blasphemy to fireworks and live sex acts. When the prestigious ICA gallery – keen for controversy – booked them to put on a show in the autumn of 1976, the group decided to give them more controversy than they could handle. Now bored with the insular art world, this would be the Coum Transmission’s swansong, an event they entitled ‘Prostitution’.

The show centred on framed pictures of Cosey in her day job – as a pornographic model – with further unorthodox displays focusing on used tampons. ‘It went brilliantly,’ Genesis said of the opening night in Jon Savage England’s Dreaming. ‘The stripper came and stripped. I got attacked by a guy from the Evening News. He came up behind me and smashed me over the head with a beer glass without saying a word. And I looked round and there he was with this glass. Then he went mad: he kicked somebody else in the balls, and then attacked three policemen outside with a brick. He got let off with a fine and then wrote this long vehement slag which triggered all the media off.’ Members of Coum duly appeared in angry newspaper headlines alongside prominent Punks, memorably dubbed ‘wreckers of civilisation’ by an outraged MP after the show inspired debate in Parliament.

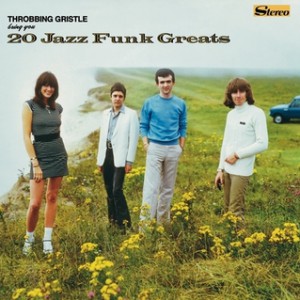

Satisfied that they had made an impact, the art collective transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle (northern English slang for an erection) and formed the Industrial Records label. ‘When we shifted from Coum Transmissions to TG, we were also stating that we wanted to go into popular culture, away from the art gallery context, and show that the same techniques that had been made to operate in that system could work,’ Genesis later explained. ‘We wanted to test it out in the real world, or nearer to the real world, at a more street level – with young kids who had no education in art perception, who came along and either empathized or didn’t; either liked the noise or didn’t.’ He was being interviewed in Industrial Culture a cult 1983 US book that was instrumental in transforming the outrageous antics of Throbbing Gristle and a few like-minded audio experimentalists – many of them on the Industrial Records label – into the basis of an international subculture.

Satisfied that they had made an impact, the art collective transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle (northern English slang for an erection) and formed the Industrial Records label. ‘When we shifted from Coum Transmissions to TG, we were also stating that we wanted to go into popular culture, away from the art gallery context, and show that the same techniques that had been made to operate in that system could work,’ Genesis later explained. ‘We wanted to test it out in the real world, or nearer to the real world, at a more street level – with young kids who had no education in art perception, who came along and either empathized or didn’t; either liked the noise or didn’t.’ He was being interviewed in Industrial Culture a cult 1983 US book that was instrumental in transforming the outrageous antics of Throbbing Gristle and a few like-minded audio experimentalists – many of them on the Industrial Records label – into the basis of an international subculture.

The acts and individuals featured in Industrial Culture – such as Non, Cabaret Voltaire and Monte Cazazza – were a motley crew, chiefly bound together by their determination to challenge taboos and accepted concepts of what qualified as music. Music shouldn’t be simple entertainment – something to lull the listener – but a sharp shock that provoked the target into life. At least as important as any audio output was the ideological, visual and performance component of this new Industrial revolution. Imagery was drawn from the most provocative sources possible – from autopsies to Nazi death camps – while gigs were often ordeals of harrowing noise and deliberately disorientating lights and visuals. It was evolving into a giant experiment – with the audiences as guinea pigs – based upon theories drawn from everywhere from arcane occultism and avant-garde art, to Beat poetry and totalitarian propaganda. It was profoundly challenging and defiantly chaotic – too strange, obnoxious and perverse to command attention from any but determined devotees of cultural excess and the masochistically pretentious.

The acts and individuals featured in Industrial Culture – such as Non, Cabaret Voltaire and Monte Cazazza – were a motley crew, chiefly bound together by their determination to challenge taboos and accepted concepts of what qualified as music. Music shouldn’t be simple entertainment – something to lull the listener – but a sharp shock that provoked the target into life. At least as important as any audio output was the ideological, visual and performance component of this new Industrial revolution. Imagery was drawn from the most provocative sources possible – from autopsies to Nazi death camps – while gigs were often ordeals of harrowing noise and deliberately disorientating lights and visuals. It was evolving into a giant experiment – with the audiences as guinea pigs – based upon theories drawn from everywhere from arcane occultism and avant-garde art, to Beat poetry and totalitarian propaganda. It was profoundly challenging and defiantly chaotic – too strange, obnoxious and perverse to command attention from any but determined devotees of cultural excess and the masochistically pretentious.

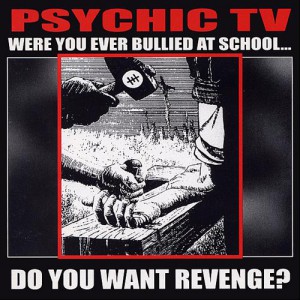

In 1981 Genesis P-Orridge had terminated Throbbing Gristle, founding Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, an organisation with self-conscious overtones of a deviant mystical cult, blended with elements borrowed from cult literature, most notably the work of the maverick Beat writer William S. Burroughs. (The deliberately dyslexic spelling reflected eccentric ideas about breaking down reality by breaking down language.) Determined to defy expectations, the movement’s musical arm, Psychic TV, began issuing Pop records. Among the more significant releases were the 1988 fake compilations Jack the Tab and Tekno Acid Beat (actually all composed by members of PTV under pseudonyms), born of P-Orridge’s interest in American Techno and Acid House music, and he’s been credited with introducing the sounds to the UK underground before electronic dance music became a mainstream phenomenon. As Industrial became established as a coherent subculture during the Eighties, it split in two distinct directions.

One faction buried further into the bowels of the underground, determined to retain the kudos of being too outrageous or oblique for popular consumption. A diverse range of obscure subgenres emerged beneath the broad banner of Industrial culture, such as Dark Ambient (sinister, synthesised soundscapes), Neofolk (Folk music with provocative imagery or lyrics), and the somewhat self-explanatory Noise music. Genesis is dismissive of many of the late arrivals to the scene. ‘Sometimes I think we’ve given birth to a monster, uncontrollable, thrashing, spewing forth mentions of Auschwitz for no reason,’ he told Savage. ‘It’s funny, because when I really think about it, the original half-dozen who started it all off are still the best ones… Whereas now they all sound like each other, and more than each other they sound like weedy fragments that they’ve honed in on, of one or the other people.’

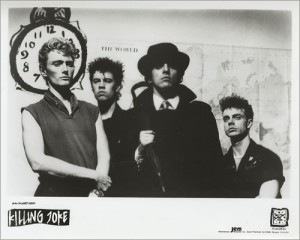

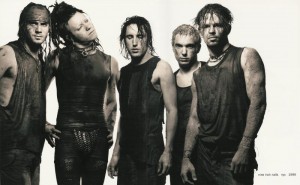

While some Industrial artists were happy to keep toiling away in obscurity, endeavouring to challenge notions of good taste on bizarre limited release recordings that only reached a tiny clique of like-minded lost souls, others saw no reason the results of their audio experiments shouldn’t reach wider audiences. These acts later became known as Electro-Industrial, developing an abrasive amalgam of ominous Synth-Pop, disturbing samples and angry attitude, a sound that could work on both darker dancefloors and among more adventurous Alternative crowds. The standard-bearers for this more aurally digestible – if equally jagged, punishing and bleak – species of Industrial included Skinny Puppy from Toronto, Chicago’s Ministry, and the London pioneers Killing Joke. However the band that brought Industrial music into the album charts was Nine Inch Nails, a project founded in 1988 in Ohio by Trent Reznor, who would become one of the most influential musicians of the Nineties.

While some Industrial artists were happy to keep toiling away in obscurity, endeavouring to challenge notions of good taste on bizarre limited release recordings that only reached a tiny clique of like-minded lost souls, others saw no reason the results of their audio experiments shouldn’t reach wider audiences. These acts later became known as Electro-Industrial, developing an abrasive amalgam of ominous Synth-Pop, disturbing samples and angry attitude, a sound that could work on both darker dancefloors and among more adventurous Alternative crowds. The standard-bearers for this more aurally digestible – if equally jagged, punishing and bleak – species of Industrial included Skinny Puppy from Toronto, Chicago’s Ministry, and the London pioneers Killing Joke. However the band that brought Industrial music into the album charts was Nine Inch Nails, a project founded in 1988 in Ohio by Trent Reznor, who would become one of the most influential musicians of the Nineties.

Reznor’s sceptical of claims that he’s popularised Industrial music. ‘There’s a scene that has been flourishing for the past five years or more,’ he told Axcess magazine in 1994. ‘Underground club oriented danceable music has been labelled industrial due to the lack of coming up with a new name… What was originally called industrial music was about 20 years ago Throbbing Gristle and Test Department. We have very little to do with it other than there is noise in my music and there is noise in theirs. I’m working in the context of a pop song structure whereas those bands didn’t. And because someone didn’t come up with a new name that separates those two somewhat unrelated genres, it tends to irritate all the old school fans waving their flags of alternativeness and obscurity. So, I’d say I’ve borrowed from certain styles and bands like that. Maybe I’ve made it more accessible. And maybe by making it more accessible it’s less exclusive. I just make music that I want to make, that’s interesting.’

It was also music that lots of people found interesting and wanted to hear, and by the late-Nineties Nine Inch Nails were enjoying high-profile commercial and critical success, with influential voices like Time magazine singing his praises, alongside numerous plaudits, awards and endorsements from within the music industry. Reznor’s successful recipe – blending traditional musicianship with cutting-edge recording technology – had a broad appeal. The driving beats and barbed guitar hooks made it both danceable and aggressive, while Reznor’s clever, troubled, deeply personal lyrics were also a powerful draw. Crucially, he also appreciated that Nine Inch Nails had to deliver live, and while there were parallels in Reznor’s downbeat introspective subject matter with Grunge, he led the pendulum swing away from the Seattle scene’s low key, ‘natural’ live style, back towards staging bombastic spectaculars on stage. ‘I’m not trying to hide, or make up for a lack of songs, but essentially Nine Inch Nails are theatre,’ explained Reznor. ‘What we do is closer to Alice Cooper than Pearl Jam.’

It was also music that lots of people found interesting and wanted to hear, and by the late-Nineties Nine Inch Nails were enjoying high-profile commercial and critical success, with influential voices like Time magazine singing his praises, alongside numerous plaudits, awards and endorsements from within the music industry. Reznor’s successful recipe – blending traditional musicianship with cutting-edge recording technology – had a broad appeal. The driving beats and barbed guitar hooks made it both danceable and aggressive, while Reznor’s clever, troubled, deeply personal lyrics were also a powerful draw. Crucially, he also appreciated that Nine Inch Nails had to deliver live, and while there were parallels in Reznor’s downbeat introspective subject matter with Grunge, he led the pendulum swing away from the Seattle scene’s low key, ‘natural’ live style, back towards staging bombastic spectaculars on stage. ‘I’m not trying to hide, or make up for a lack of songs, but essentially Nine Inch Nails are theatre,’ explained Reznor. ‘What we do is closer to Alice Cooper than Pearl Jam.’

Initially, Nine Inch Nails – and his high profile protégé ‘Antichrist Superstar’ Marilyn Manson – attracted a large following among the Goth crowd. Reznor’s black clothing and eyeliner image chimed with Goths, as did the thoughtful, spiky lyrics. But it was the Heavy Metal community that embraced Nine Inch Nails most enthusiastically, and as the band’s music began to chart, many Goths began to dismiss them as sell-outs, similarly disowning Manson and his building legion of fans as counterfeit Goths. Meanwhile, by the late-Nineties ‘Industrial’ had become the buzzword on the Metal scene, as even long-established artists recorded tracks in the signature, grinding inorganic sound, or started Industrial side-projects. Even Hip Hop wasn’t immune to Industrial’s caustic charms, and some even refer to a specific subgenre of Industrial Hip Hop, though in truth the crossover bore little fruit, certainly in comparison to the powerful impact Industrial had on cutting-edge Metal.

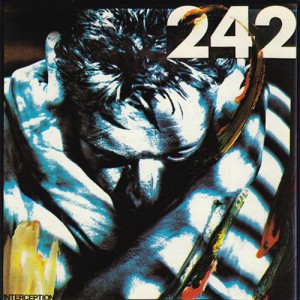

While the increasing intrusion of muscular guitars alienated many Goths from Nineties Industrial music, as increasingly defined in many eyes by Nine Inch Nails, they didn’t abandon the genre entirely. Parallel to the emergence of the Rock-influenced species of Industrial was a version that cross-pollinated with the vibrant dance scene emerging in the post-Disco era. The term ‘Electronic Body Music’ was coined by Kraftwerk – part of the influential Krautrock movement of German bands exploring new technology in the Seventies – and EBM became a genre in its own right in the Eighties. In particular, the Belgian band Front 242 popularised the term with a sound that fused Kraftwerk’s pounding rhythms and repetitive melodies with Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational attitude. For those drawn to the mesmeric beat of Techno, but turned off by its relentlessly up-tempo ethos and mindless mainstream image, EBM was a revelation, opening up new musical horizons.

While the increasing intrusion of muscular guitars alienated many Goths from Nineties Industrial music, as increasingly defined in many eyes by Nine Inch Nails, they didn’t abandon the genre entirely. Parallel to the emergence of the Rock-influenced species of Industrial was a version that cross-pollinated with the vibrant dance scene emerging in the post-Disco era. The term ‘Electronic Body Music’ was coined by Kraftwerk – part of the influential Krautrock movement of German bands exploring new technology in the Seventies – and EBM became a genre in its own right in the Eighties. In particular, the Belgian band Front 242 popularised the term with a sound that fused Kraftwerk’s pounding rhythms and repetitive melodies with Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational attitude. For those drawn to the mesmeric beat of Techno, but turned off by its relentlessly up-tempo ethos and mindless mainstream image, EBM was a revelation, opening up new musical horizons.

EBM took many Goth clubs by storm in the late-Nineties, sweeping more traditional Post-Punk and Gothic Rock sounds from playlists as trend-savvy DJs noticed that it invariably filled the dancefloor. Traditionalists blamed the development on the increasing presence of ecstasy pills on the scene, and dismissed EBM as mainstream Techno in an unconvincing disguise. Yet they were fighting against the tide, and by the end of the Nineties Cybergoth was the hottest new style on the London Goth scene, a look that dispensed with the funereal Victoriana of Trad Goth in favour of an image that owed more to Rave culture and science fiction than the Gothic aesthetic. Black lace, incense and flowing gowns were yesterday’s news, in favour of PVC, luminous colours, lurid artificial hair and glow-sticks. Traditional Goth styles of dance – melodramatic and wistful – also began falling out of vogue, displaced by the more energetic moves demanded by an incessant electronic beat.

There was much cross-pollination with Rivethead subculture, which developed in parallel to Cybergoth. While Cybergoth was as camp as classic Goth, if in a futuristic fashion, Rivethead was a more masculine style adopted by aficionados of Industrial music, who stomped onto the scene in the late-Nineties. The stereotypical Industrial fan of the Eighties – inasmuch as there was one when the scene was so diverse – wore black army surplus gear and boots. A few favoured military symbols or even uniforms with incendiary nationalist overtones, though for most this was just an extension of early Industrial’s shock aesthetic. Rivetheads retained the military look, but discarded the ugly ideological baggage, adding a post-apocalyptic Mad Max-style spin that owed something to Punk and even more to the imagery of heavy industry. Think goggles (also favoured by Cybergoths), heavy boots, piercings, dreadlocks, Mohicans and nuclear or biohazard symbols – an image that embodied the original Industrial Records slogan of ‘Industrial Music for Industrial People’ – even if it’s not what was envisaged way back in 1976.

The story of Industrial music is emblematic of a question that echoes throughout this book – who gets to define a specific genre or subculture? Genesis P-Orridge and his maverick co-conspirators meant something entirely different when they coined the term, but ‘Industrial music’ captured the popular imagination when artists and fans reinterpreted it as a license to explore new musical technology. The technical innovations initially regarded with great suspicion by many Rock artists and fans are now accepted tools in the recording process. The style certainly broke down boundaries – explored new territories – but ‘Industrial’ is no longer the buzzword for innovation it once was. The shock tactics of the originators have grown stale, the technological innovations have inevitably dated. ‘Industrial culture?’ ponders Genesis. ‘There has been a phenomena; I don’t know whether it’s strong enough to be a culture. I do think what we did has had a reverberation right around the world and back.’

ISIS By Any Other Name…

I’ve found the ongoing pompous debate over what we should call ISIS (or ISIL or Daesh) simultaneously entertaining and exasperating. I instinctively bristle when anybody tries to tell me which words I should – or even can – use. Particularly because said language police are almost invariably pontificating from their posteriors.

This is mostly certainly the case in this debate.

Many Western commentators – including numerous high profile figures who presumably have squads of researchers at their beck and call – are keen we stop using ISIS because, they sagely inform us, Daesh is the correct term. ISIS contains the words ‘Islamic’ and ‘State’, and we don’t want to dignify these people with either designation. Far better Daesh, because Arabs use it on the ground, because it is an insult.

Only it isn’t. It’s simply the Arabic for exactly the same acronym as ISIS, complete with the words Islamic and State. D’oh. In fact, if anything, by insisting on this change I’d argue you’re insulting the Islamic world further by not even bothering to make even basic attempts to understand the Arabic words you’re misappropriating. (For extra pedant points, the second ‘S’ in ISIS refers to Sham, not Syria. Sham is the region containing Syria. Confusing the two is akin to thinking England and Britain are interchangable.)

More importantly, the ideas behind this posturing are at best flawed. Removing ‘Islamic’ from the acronym won’t stop ISIS being Muslims any more than rebranding a Big Mac as a lettuce sandwich will make it healthy. Similarly Islamic State isn’t a state? Maybe, but by the same lofty definitions applied in this argument – of good governance and respecting the niceties of basic human rights – neither are many of our Muslim, slave-owning allies in the region. And if they aren’t states, why are we selling them so many arms?

Hmmm. I’m reminded of those wearying historical wags who never tire of reminding us that the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy nor an empire. Perhaps. But you try describing Renaissance European history without the term. Terminology twists and adapts to suit the subject it describes. You can’t make Islam the religion of peace simply by insisting that anybody who does anything wrong is ergo no longer a Muslim. There’s been way too much blood for that to wash.

So what’s the solution? If we abandon ISIS then has the dog from Downton Abbey died in vain? ISIL seems like a pointless compromise, and sounds like a fabric conditioner. Daesh just seems to underline Western ignorance of the situation in the Middle East, which is what got us into this shit in the first place. How about returning to ISIS’s original moniker?

If we started calling them Jama’at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad again it would surely deprive them if the oxygen of publicity, because none of us can fucking pronounce it.

A Countercultural Conversation

My publisher suggested I conduct a brief interview to promote my new book Street Culture: 50 Years of Subculture Style. So I recorded a brief conversation with the actress Natalie Boyd, in which we discuss the ideas behind the book, what I learnt writing it, and what the future might hold for the colourful world of counterculture. With thanks to the wonderful folk at Ink Blot Films for providing the expertise and equipment at such short notice.

Time to Panic…

Those with an interest in matters demonic, will be interested in this intriguing book due out later this year. Entitled Satanic Panic: Pop Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, it features a range of insightful essays and interviews from established authors, and up-and-coming talents, including a contribution from yours truly. For more details on this exciting project from Canadian publisher Spectacular Optical, as well as how you can avail yourselves of a range of Satanic special offers via crowd-funding, check out the book’s Indiegogo page here.

Those with an interest in matters demonic, will be interested in this intriguing book due out later this year. Entitled Satanic Panic: Pop Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s, it features a range of insightful essays and interviews from established authors, and up-and-coming talents, including a contribution from yours truly. For more details on this exciting project from Canadian publisher Spectacular Optical, as well as how you can avail yourselves of a range of Satanic special offers via crowd-funding, check out the book’s Indiegogo page here.