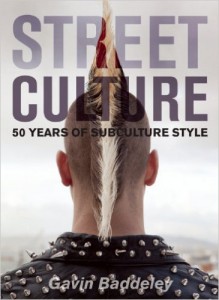

My new book, Street Culture should be hitting the streets soon. Like all of my books, there were compromises and editorial decisions taken during its composition. In order to fit the format my publisher liked, we had to cut some material. A few chapters were truncated. Others were assimilated into earlier chapters. For example, I originally had a chapter on the Scooter Boys, Soulies and Mod Revivalists that followed in the wake of the first wave of Mod, but who were sufficiently different to qualify as a new species. Sadly, space meant condensing them into a postscript in the Mod chapter.

My new book, Street Culture should be hitting the streets soon. Like all of my books, there were compromises and editorial decisions taken during its composition. In order to fit the format my publisher liked, we had to cut some material. A few chapters were truncated. Others were assimilated into earlier chapters. For example, I originally had a chapter on the Scooter Boys, Soulies and Mod Revivalists that followed in the wake of the first wave of Mod, but who were sufficiently different to qualify as a new species. Sadly, space meant condensing them into a postscript in the Mod chapter.

A couple of chapters pretty much disappeared in their entirety. Among these was the one on the Industrial subculture. This was a shame as, while I understood my publisher’s reasoning that they weren’t very well known, this also qualifies as an argument to keep them in. Certainly, in the 90s, industrial music and the accompanying aesthetic carved a significant place for itself in the no-man’s-land between Punk, Goth, Metal and Rave, having a notable impact on the scenes it touched upon. Anyhow, rather than waste the chapter, I thought I’d share it here. Please bear in mind that this is raw, unedited text, so likely contains numerous typos and mistakes. I hope you enjoy it anyway.

As with everything on this site. It’s (c) Gavin Baddeley. Do share, but show respect and professionalism and retain appropriate credits, links and suchlike please.

INDUSTRIALISTS & RIVET-HEADS

By many accounts, the Industrial movement is largely the result of a misunderstanding. The term was its origins with the American experimental musician and controversialist Monte Cazazza, who suggested the slogan ‘Industrial Music for Industrial People’ for the Industrial Records label, founded in the UK in 1976. The use of the term industrial in this context had several implications. In part it was an arch comment on the idea that a creative discipline like music could be an ‘industry’. In part it reflected the idea that, now most people laboured in factories rather than tilling fields, a new form of music was necessary that would address this profound change, something wholly different from Rock. Above all it was a provocative, eye-catching moniker for art designed to break down barriers. By the Eighties, Industrial was being re-interpreted as simply referring to any music made predominantly with electronic or mechanical equipment, which wasn’t what the originators had in mind at all.

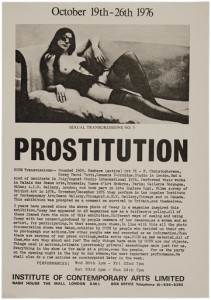

It’s perhaps significant that the Industrial label was founded in London at the height of the Punk explosion, caught up in the same initial frenzy of press outrage. Both movements had roots in the UK’s art schools. While Punk used fashion as a springboard to national notoriety via Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex boutique on the King’s Road, Industrial’s more low profile rise to infamy took place within the art world. Coum Transmission was an avant-garde art collective formed in 1969, with Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Megson) and Cosey Fanni Tutti (Christine Newby) at its core. They specialised in confrontational displays featuring everything from sadomasochism and blasphemy to fireworks and live sex acts. When the prestigious ICA gallery – keen for controversy – booked them to put on a show in the autumn of 1976, the group decided to give them more controversy than they could handle. Now bored with the insular art world, this would be the Coum Transmission’s swansong, an event they entitled ‘Prostitution’.

It’s perhaps significant that the Industrial label was founded in London at the height of the Punk explosion, caught up in the same initial frenzy of press outrage. Both movements had roots in the UK’s art schools. While Punk used fashion as a springboard to national notoriety via Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Sex boutique on the King’s Road, Industrial’s more low profile rise to infamy took place within the art world. Coum Transmission was an avant-garde art collective formed in 1969, with Genesis P-Orridge (Neil Megson) and Cosey Fanni Tutti (Christine Newby) at its core. They specialised in confrontational displays featuring everything from sadomasochism and blasphemy to fireworks and live sex acts. When the prestigious ICA gallery – keen for controversy – booked them to put on a show in the autumn of 1976, the group decided to give them more controversy than they could handle. Now bored with the insular art world, this would be the Coum Transmission’s swansong, an event they entitled ‘Prostitution’.

The show centred on framed pictures of Cosey in her day job – as a pornographic model – with further unorthodox displays focusing on used tampons. ‘It went brilliantly,’ Genesis said of the opening night in Jon Savage England’s Dreaming. ‘The stripper came and stripped. I got attacked by a guy from the Evening News. He came up behind me and smashed me over the head with a beer glass without saying a word. And I looked round and there he was with this glass. Then he went mad: he kicked somebody else in the balls, and then attacked three policemen outside with a brick. He got let off with a fine and then wrote this long vehement slag which triggered all the media off.’ Members of Coum duly appeared in angry newspaper headlines alongside prominent Punks, memorably dubbed ‘wreckers of civilisation’ by an outraged MP after the show inspired debate in Parliament.

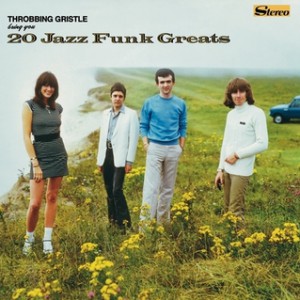

Satisfied that they had made an impact, the art collective transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle (northern English slang for an erection) and formed the Industrial Records label. ‘When we shifted from Coum Transmissions to TG, we were also stating that we wanted to go into popular culture, away from the art gallery context, and show that the same techniques that had been made to operate in that system could work,’ Genesis later explained. ‘We wanted to test it out in the real world, or nearer to the real world, at a more street level – with young kids who had no education in art perception, who came along and either empathized or didn’t; either liked the noise or didn’t.’ He was being interviewed in Industrial Culture a cult 1983 US book that was instrumental in transforming the outrageous antics of Throbbing Gristle and a few like-minded audio experimentalists – many of them on the Industrial Records label – into the basis of an international subculture.

Satisfied that they had made an impact, the art collective transformed into the band Throbbing Gristle (northern English slang for an erection) and formed the Industrial Records label. ‘When we shifted from Coum Transmissions to TG, we were also stating that we wanted to go into popular culture, away from the art gallery context, and show that the same techniques that had been made to operate in that system could work,’ Genesis later explained. ‘We wanted to test it out in the real world, or nearer to the real world, at a more street level – with young kids who had no education in art perception, who came along and either empathized or didn’t; either liked the noise or didn’t.’ He was being interviewed in Industrial Culture a cult 1983 US book that was instrumental in transforming the outrageous antics of Throbbing Gristle and a few like-minded audio experimentalists – many of them on the Industrial Records label – into the basis of an international subculture.

The acts and individuals featured in Industrial Culture – such as Non, Cabaret Voltaire and Monte Cazazza – were a motley crew, chiefly bound together by their determination to challenge taboos and accepted concepts of what qualified as music. Music shouldn’t be simple entertainment – something to lull the listener – but a sharp shock that provoked the target into life. At least as important as any audio output was the ideological, visual and performance component of this new Industrial revolution. Imagery was drawn from the most provocative sources possible – from autopsies to Nazi death camps – while gigs were often ordeals of harrowing noise and deliberately disorientating lights and visuals. It was evolving into a giant experiment – with the audiences as guinea pigs – based upon theories drawn from everywhere from arcane occultism and avant-garde art, to Beat poetry and totalitarian propaganda. It was profoundly challenging and defiantly chaotic – too strange, obnoxious and perverse to command attention from any but determined devotees of cultural excess and the masochistically pretentious.

The acts and individuals featured in Industrial Culture – such as Non, Cabaret Voltaire and Monte Cazazza – were a motley crew, chiefly bound together by their determination to challenge taboos and accepted concepts of what qualified as music. Music shouldn’t be simple entertainment – something to lull the listener – but a sharp shock that provoked the target into life. At least as important as any audio output was the ideological, visual and performance component of this new Industrial revolution. Imagery was drawn from the most provocative sources possible – from autopsies to Nazi death camps – while gigs were often ordeals of harrowing noise and deliberately disorientating lights and visuals. It was evolving into a giant experiment – with the audiences as guinea pigs – based upon theories drawn from everywhere from arcane occultism and avant-garde art, to Beat poetry and totalitarian propaganda. It was profoundly challenging and defiantly chaotic – too strange, obnoxious and perverse to command attention from any but determined devotees of cultural excess and the masochistically pretentious.

In 1981 Genesis P-Orridge had terminated Throbbing Gristle, founding Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, an organisation with self-conscious overtones of a deviant mystical cult, blended with elements borrowed from cult literature, most notably the work of the maverick Beat writer William S. Burroughs. (The deliberately dyslexic spelling reflected eccentric ideas about breaking down reality by breaking down language.) Determined to defy expectations, the movement’s musical arm, Psychic TV, began issuing Pop records. Among the more significant releases were the 1988 fake compilations Jack the Tab and Tekno Acid Beat (actually all composed by members of PTV under pseudonyms), born of P-Orridge’s interest in American Techno and Acid House music, and he’s been credited with introducing the sounds to the UK underground before electronic dance music became a mainstream phenomenon. As Industrial became established as a coherent subculture during the Eighties, it split in two distinct directions.

One faction buried further into the bowels of the underground, determined to retain the kudos of being too outrageous or oblique for popular consumption. A diverse range of obscure subgenres emerged beneath the broad banner of Industrial culture, such as Dark Ambient (sinister, synthesised soundscapes), Neofolk (Folk music with provocative imagery or lyrics), and the somewhat self-explanatory Noise music. Genesis is dismissive of many of the late arrivals to the scene. ‘Sometimes I think we’ve given birth to a monster, uncontrollable, thrashing, spewing forth mentions of Auschwitz for no reason,’ he told Savage. ‘It’s funny, because when I really think about it, the original half-dozen who started it all off are still the best ones… Whereas now they all sound like each other, and more than each other they sound like weedy fragments that they’ve honed in on, of one or the other people.’

While some Industrial artists were happy to keep toiling away in obscurity, endeavouring to challenge notions of good taste on bizarre limited release recordings that only reached a tiny clique of like-minded lost souls, others saw no reason the results of their audio experiments shouldn’t reach wider audiences. These acts later became known as Electro-Industrial, developing an abrasive amalgam of ominous Synth-Pop, disturbing samples and angry attitude, a sound that could work on both darker dancefloors and among more adventurous Alternative crowds. The standard-bearers for this more aurally digestible – if equally jagged, punishing and bleak – species of Industrial included Skinny Puppy from Toronto, Chicago’s Ministry, and the London pioneers Killing Joke. However the band that brought Industrial music into the album charts was Nine Inch Nails, a project founded in 1988 in Ohio by Trent Reznor, who would become one of the most influential musicians of the Nineties.

While some Industrial artists were happy to keep toiling away in obscurity, endeavouring to challenge notions of good taste on bizarre limited release recordings that only reached a tiny clique of like-minded lost souls, others saw no reason the results of their audio experiments shouldn’t reach wider audiences. These acts later became known as Electro-Industrial, developing an abrasive amalgam of ominous Synth-Pop, disturbing samples and angry attitude, a sound that could work on both darker dancefloors and among more adventurous Alternative crowds. The standard-bearers for this more aurally digestible – if equally jagged, punishing and bleak – species of Industrial included Skinny Puppy from Toronto, Chicago’s Ministry, and the London pioneers Killing Joke. However the band that brought Industrial music into the album charts was Nine Inch Nails, a project founded in 1988 in Ohio by Trent Reznor, who would become one of the most influential musicians of the Nineties.

Reznor’s sceptical of claims that he’s popularised Industrial music. ‘There’s a scene that has been flourishing for the past five years or more,’ he told Axcess magazine in 1994. ‘Underground club oriented danceable music has been labelled industrial due to the lack of coming up with a new name… What was originally called industrial music was about 20 years ago Throbbing Gristle and Test Department. We have very little to do with it other than there is noise in my music and there is noise in theirs. I’m working in the context of a pop song structure whereas those bands didn’t. And because someone didn’t come up with a new name that separates those two somewhat unrelated genres, it tends to irritate all the old school fans waving their flags of alternativeness and obscurity. So, I’d say I’ve borrowed from certain styles and bands like that. Maybe I’ve made it more accessible. And maybe by making it more accessible it’s less exclusive. I just make music that I want to make, that’s interesting.’

It was also music that lots of people found interesting and wanted to hear, and by the late-Nineties Nine Inch Nails were enjoying high-profile commercial and critical success, with influential voices like Time magazine singing his praises, alongside numerous plaudits, awards and endorsements from within the music industry. Reznor’s successful recipe – blending traditional musicianship with cutting-edge recording technology – had a broad appeal. The driving beats and barbed guitar hooks made it both danceable and aggressive, while Reznor’s clever, troubled, deeply personal lyrics were also a powerful draw. Crucially, he also appreciated that Nine Inch Nails had to deliver live, and while there were parallels in Reznor’s downbeat introspective subject matter with Grunge, he led the pendulum swing away from the Seattle scene’s low key, ‘natural’ live style, back towards staging bombastic spectaculars on stage. ‘I’m not trying to hide, or make up for a lack of songs, but essentially Nine Inch Nails are theatre,’ explained Reznor. ‘What we do is closer to Alice Cooper than Pearl Jam.’

It was also music that lots of people found interesting and wanted to hear, and by the late-Nineties Nine Inch Nails were enjoying high-profile commercial and critical success, with influential voices like Time magazine singing his praises, alongside numerous plaudits, awards and endorsements from within the music industry. Reznor’s successful recipe – blending traditional musicianship with cutting-edge recording technology – had a broad appeal. The driving beats and barbed guitar hooks made it both danceable and aggressive, while Reznor’s clever, troubled, deeply personal lyrics were also a powerful draw. Crucially, he also appreciated that Nine Inch Nails had to deliver live, and while there were parallels in Reznor’s downbeat introspective subject matter with Grunge, he led the pendulum swing away from the Seattle scene’s low key, ‘natural’ live style, back towards staging bombastic spectaculars on stage. ‘I’m not trying to hide, or make up for a lack of songs, but essentially Nine Inch Nails are theatre,’ explained Reznor. ‘What we do is closer to Alice Cooper than Pearl Jam.’

Initially, Nine Inch Nails – and his high profile protégé ‘Antichrist Superstar’ Marilyn Manson – attracted a large following among the Goth crowd. Reznor’s black clothing and eyeliner image chimed with Goths, as did the thoughtful, spiky lyrics. But it was the Heavy Metal community that embraced Nine Inch Nails most enthusiastically, and as the band’s music began to chart, many Goths began to dismiss them as sell-outs, similarly disowning Manson and his building legion of fans as counterfeit Goths. Meanwhile, by the late-Nineties ‘Industrial’ had become the buzzword on the Metal scene, as even long-established artists recorded tracks in the signature, grinding inorganic sound, or started Industrial side-projects. Even Hip Hop wasn’t immune to Industrial’s caustic charms, and some even refer to a specific subgenre of Industrial Hip Hop, though in truth the crossover bore little fruit, certainly in comparison to the powerful impact Industrial had on cutting-edge Metal.

While the increasing intrusion of muscular guitars alienated many Goths from Nineties Industrial music, as increasingly defined in many eyes by Nine Inch Nails, they didn’t abandon the genre entirely. Parallel to the emergence of the Rock-influenced species of Industrial was a version that cross-pollinated with the vibrant dance scene emerging in the post-Disco era. The term ‘Electronic Body Music’ was coined by Kraftwerk – part of the influential Krautrock movement of German bands exploring new technology in the Seventies – and EBM became a genre in its own right in the Eighties. In particular, the Belgian band Front 242 popularised the term with a sound that fused Kraftwerk’s pounding rhythms and repetitive melodies with Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational attitude. For those drawn to the mesmeric beat of Techno, but turned off by its relentlessly up-tempo ethos and mindless mainstream image, EBM was a revelation, opening up new musical horizons.

While the increasing intrusion of muscular guitars alienated many Goths from Nineties Industrial music, as increasingly defined in many eyes by Nine Inch Nails, they didn’t abandon the genre entirely. Parallel to the emergence of the Rock-influenced species of Industrial was a version that cross-pollinated with the vibrant dance scene emerging in the post-Disco era. The term ‘Electronic Body Music’ was coined by Kraftwerk – part of the influential Krautrock movement of German bands exploring new technology in the Seventies – and EBM became a genre in its own right in the Eighties. In particular, the Belgian band Front 242 popularised the term with a sound that fused Kraftwerk’s pounding rhythms and repetitive melodies with Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational attitude. For those drawn to the mesmeric beat of Techno, but turned off by its relentlessly up-tempo ethos and mindless mainstream image, EBM was a revelation, opening up new musical horizons.

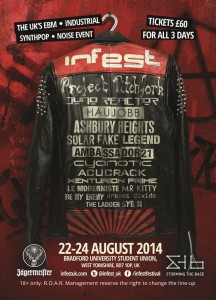

EBM took many Goth clubs by storm in the late-Nineties, sweeping more traditional Post-Punk and Gothic Rock sounds from playlists as trend-savvy DJs noticed that it invariably filled the dancefloor. Traditionalists blamed the development on the increasing presence of ecstasy pills on the scene, and dismissed EBM as mainstream Techno in an unconvincing disguise. Yet they were fighting against the tide, and by the end of the Nineties Cybergoth was the hottest new style on the London Goth scene, a look that dispensed with the funereal Victoriana of Trad Goth in favour of an image that owed more to Rave culture and science fiction than the Gothic aesthetic. Black lace, incense and flowing gowns were yesterday’s news, in favour of PVC, luminous colours, lurid artificial hair and glow-sticks. Traditional Goth styles of dance – melodramatic and wistful – also began falling out of vogue, displaced by the more energetic moves demanded by an incessant electronic beat.

There was much cross-pollination with Rivethead subculture, which developed in parallel to Cybergoth. While Cybergoth was as camp as classic Goth, if in a futuristic fashion, Rivethead was a more masculine style adopted by aficionados of Industrial music, who stomped onto the scene in the late-Nineties. The stereotypical Industrial fan of the Eighties – inasmuch as there was one when the scene was so diverse – wore black army surplus gear and boots. A few favoured military symbols or even uniforms with incendiary nationalist overtones, though for most this was just an extension of early Industrial’s shock aesthetic. Rivetheads retained the military look, but discarded the ugly ideological baggage, adding a post-apocalyptic Mad Max-style spin that owed something to Punk and even more to the imagery of heavy industry. Think goggles (also favoured by Cybergoths), heavy boots, piercings, dreadlocks, Mohicans and nuclear or biohazard symbols – an image that embodied the original Industrial Records slogan of ‘Industrial Music for Industrial People’ – even if it’s not what was envisaged way back in 1976.

The story of Industrial music is emblematic of a question that echoes throughout this book – who gets to define a specific genre or subculture? Genesis P-Orridge and his maverick co-conspirators meant something entirely different when they coined the term, but ‘Industrial music’ captured the popular imagination when artists and fans reinterpreted it as a license to explore new musical technology. The technical innovations initially regarded with great suspicion by many Rock artists and fans are now accepted tools in the recording process. The style certainly broke down boundaries – explored new territories – but ‘Industrial’ is no longer the buzzword for innovation it once was. The shock tactics of the originators have grown stale, the technological innovations have inevitably dated. ‘Industrial culture?’ ponders Genesis. ‘There has been a phenomena; I don’t know whether it’s strong enough to be a culture. I do think what we did has had a reverberation right around the world and back.’