Part One: Born to Be Wild

My recent annual pilgrimage to the Bloodstock Open Air heavy metal festival’s inspired me to meditate on matters metallic and heavy, particularly of the primordial variety. ‘Primordial’s one of the terms frequently associated with the genre. Indeed, as anyone who’s ever written much about metal at any length can confirm, one of the challenges is finding new adjectives to employ after the more obvious candidates have been done-to-death. I can’t be the only metal scribe who’s found themselves driven in desperation to the thesaurus looking for fresh ways of saying ‘ominous’, ‘brutal’, ‘thunderous’, and suchlike. And I’ve been in this game in one form or another far longer than I’d care to recall.

When I first started putting finger to keyboard on the topic, serious studies of the genre and its associated subculture were notably thin on the ground. In recent years, a substantial library of texts – many of them impenetrably (and I’d suggest often risibly) academic – has accumulated. Of course, the cultural landscape has shifted quite a bit. For example, many bands once regarded as mainstays of the metal genre – the likes of Nazareth or Uriah Heep – have since long been pensioned off into the general rock section. Muddying the waters, heavy metal only really established itself as common parlance gradually during the 70s, allowing for myriad interpretations as it evolved and reinvented itself throughout the decade.

Most, however, now agree that the first fully-fledged heavy metal album was Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut, giving the genre a date-of-birth of Friday the 13th of February, 1970. Identifying the genre’s prehistory, however, takes the metal scholar into more controversial territory. When I’ve been trying to excavate metal’s roots I frequently find myself at odds with the orthodox version of events. Bands and songs routinely referred to as the genre’s direct ancestors often feel instinctively wrong. So, if you’ll indulge me in a brace of little essays, I’d like to ponder the movement’s prehistory, before offering my own unorthodox candidate for the mantle of heavy metal’s forefathers. In the process I’ll be offering the odd personal perspective on what I – as a lifelong fan – think makes heavy metal, well, heavy metal…

Most, however, now agree that the first fully-fledged heavy metal album was Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut, giving the genre a date-of-birth of Friday the 13th of February, 1970. Identifying the genre’s prehistory, however, takes the metal scholar into more controversial territory. When I’ve been trying to excavate metal’s roots I frequently find myself at odds with the orthodox version of events. Bands and songs routinely referred to as the genre’s direct ancestors often feel instinctively wrong. So, if you’ll indulge me in a brace of little essays, I’d like to ponder the movement’s prehistory, before offering my own unorthodox candidate for the mantle of heavy metal’s forefathers. In the process I’ll be offering the odd personal perspective on what I – as a lifelong fan – think makes heavy metal, well, heavy metal…

The origins of the term itself are obscure. ‘Heavy’ is hippie slang for ominous, serious or grave – all adjectives appropriate to the genre. The ‘metal’ part is more difficult to pin down. Outside of the realms of pop culture, in chemical terms ‘heavy metal’ refers to metals with unusual density or toxicity, such as lead or cadmium. But there appears to be little more than coincidental connections between this scientific term and the musical subculture we’re putting under the microscope here. In our context, the term doesn’t really mean anything. Perhaps that’s part of the secret of the subculture’s longevity, as such ambiguity allows for an elasticity of definition. In other words, if ‘heavy metal’ as a phrase effectively meant nothing, it could potentially mean anything.

Other comparable subcultures have laboured under more explicit, hence limiting, inappropriate or unhelpful, monikers. Mod, for example, was an abbreviation of ‘Modernist’ when the movement emerged in the early 60s. Today, Mod’s one of the most backward-looking, nostalgia-bound subculture to be found on the streets. While I’d contend that the Gothic elements are the most interesting aspects of the Goth movement, many devotees think the emphasis on all things dark and gloomy is misleading and unnecessarily brands Goths as clichéd miserablists. By way of contrast, while the phrase ‘heavy metal’ implies ideas about power and strength, it remains abstract – open to reinterpretation and evolution.

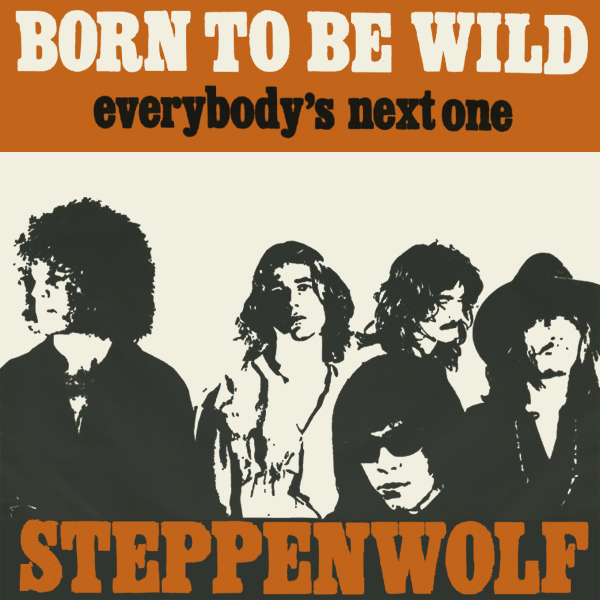

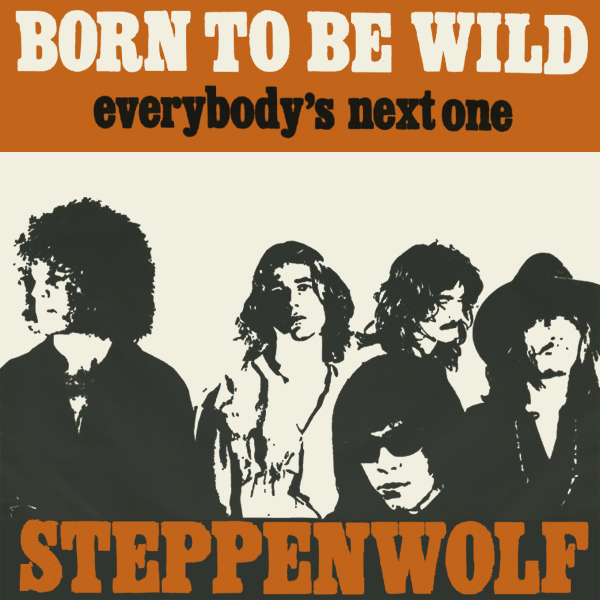

But, for all that, the term must’ve come from somewhere. Theories about its genesis range from references in the work of the druggy beat author William Burroughs, to language used in live reviews of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. A more concrete source can be found in the 1968 Steppenwolf song ‘Born to be Wild’. The lyrics ‘I like smoke and lightning, Heavy metal thunder, Racing with the wind, And the feeling that I’m under’ not only likely represent the first use of the terminology in a song, but also capture something of the ethos that would come to epitomise the spirit of heavy metal – a tempestuous passion for Wagnerian melodrama, an evocation of nature red in tooth and claw.

But, for all that, the term must’ve come from somewhere. Theories about its genesis range from references in the work of the druggy beat author William Burroughs, to language used in live reviews of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. A more concrete source can be found in the 1968 Steppenwolf song ‘Born to be Wild’. The lyrics ‘I like smoke and lightning, Heavy metal thunder, Racing with the wind, And the feeling that I’m under’ not only likely represent the first use of the terminology in a song, but also capture something of the ethos that would come to epitomise the spirit of heavy metal – a tempestuous passion for Wagnerian melodrama, an evocation of nature red in tooth and claw.

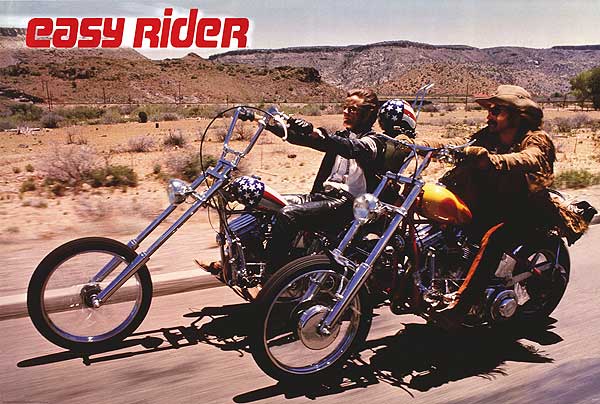

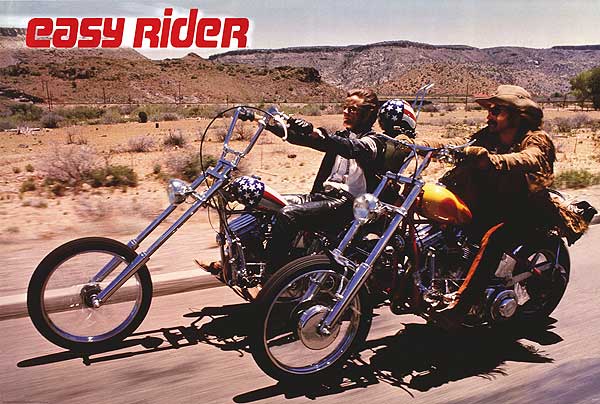

Crucially, however, it was the song’s prominent inclusion in the soundtrack to the iconic biker flick ‘Easy Rider’ the following year that ensured the song’s immortality. Within that context, the previously ambiguous ‘heavy metal’ now clearly refers to the custom Harleys at the core of the film (revving bike engines introduce the song on the soundtrack album). Motorbikes – particularly big, American customised bikes – quickly became iconic in metal culture. Though the relationship between metal and the outlaw biker subculture was often initially akin to that between an overly eager youngster and his cooler older brother – metalheads liked bikes more than most bikers liked metal – there’s more than one band promo shot where the metal heroes are sat astride borrowed motorbikes.

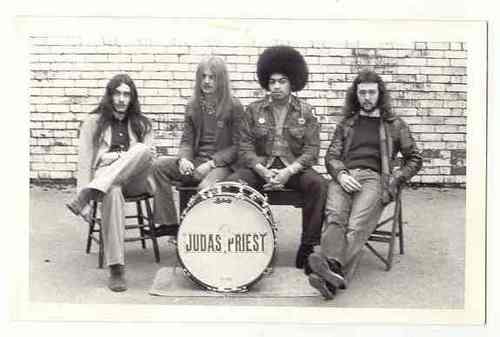

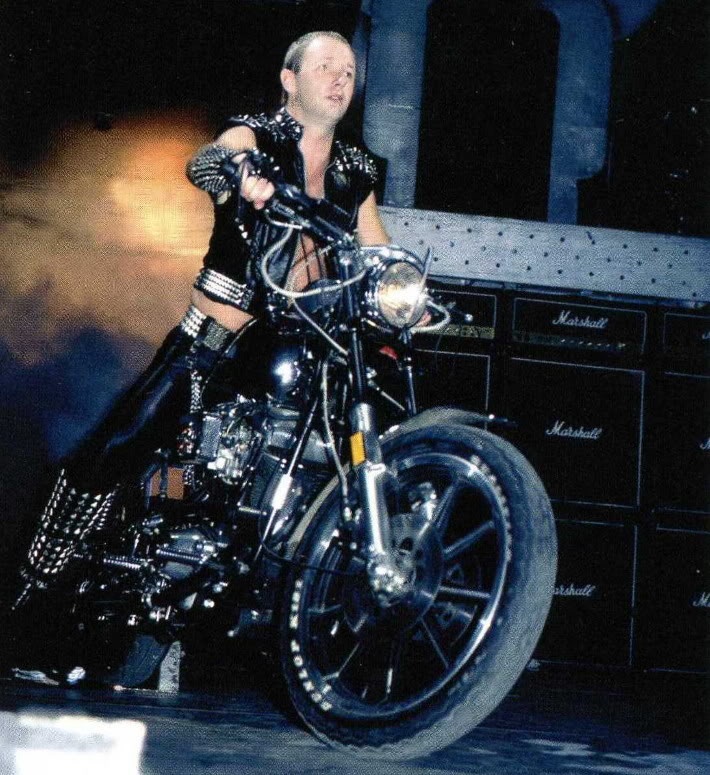

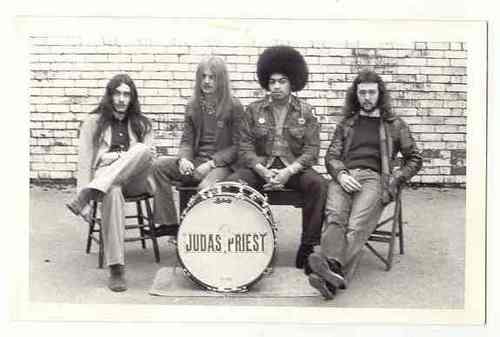

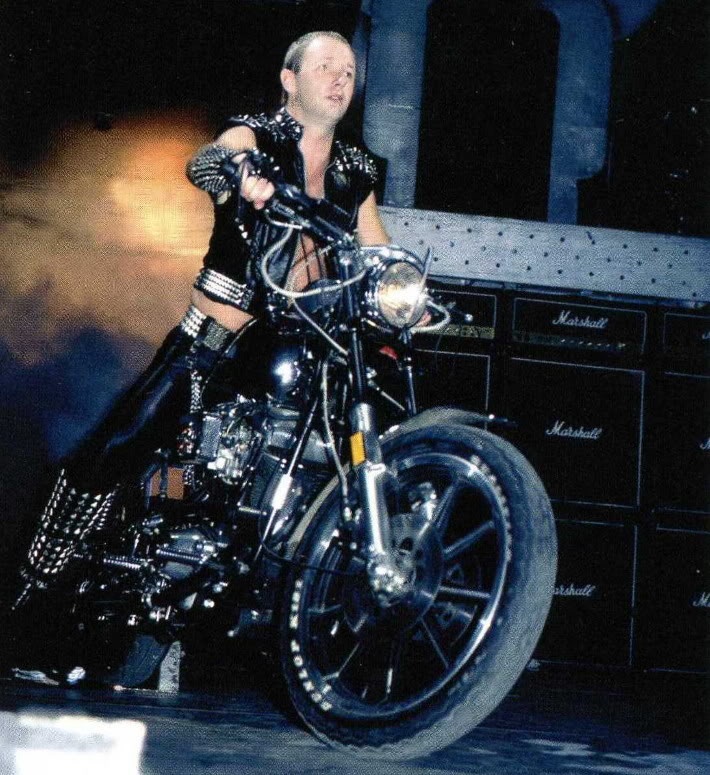

The band that did more to establish heavy metal style than most was England’s Judas Priest. Founded in 1969, they evolved from a generic hippie hard rock outfit, via a brief psychedelic silken prog stage, to the stereotypical leatherclad metal outfit. ‘The whole association with motorcycles and Judas Priest goes back to [1978 release] ‘Hell Bent for Leather’,’ the band’s vocalist Rob Halford reflected. ‘When we were touring in England, we thought that it would be cool if we could bring the bike on stage when we did the song.’ Yet, despite the leather and chains, Halford was no biker, and in one of metal’s more unedifying episodes collided with a stage prop while astride the bike while performing in 1990. The singer suffered a broken nose and was knocked out, though as a true trooper concluded the show as soon as he came round.

The band that did more to establish heavy metal style than most was England’s Judas Priest. Founded in 1969, they evolved from a generic hippie hard rock outfit, via a brief psychedelic silken prog stage, to the stereotypical leatherclad metal outfit. ‘The whole association with motorcycles and Judas Priest goes back to [1978 release] ‘Hell Bent for Leather’,’ the band’s vocalist Rob Halford reflected. ‘When we were touring in England, we thought that it would be cool if we could bring the bike on stage when we did the song.’ Yet, despite the leather and chains, Halford was no biker, and in one of metal’s more unedifying episodes collided with a stage prop while astride the bike while performing in 1990. The singer suffered a broken nose and was knocked out, though as a true trooper concluded the show as soon as he came round.

In truth, powerful custom bikes have long been largely the stuff of fantasy for many young metal fans, alongside other iconic imagery, from battleaxes and expensive guitars, to demons and improbably chesty ladies-of-easy-virtue. Romantic escapism has always been at the core of the subculture’s allure. Few worldly fans were surprised when it became clear that the band’s wardrobe came, not from a Hell’s Angels chop shop, but an S/M boutique aimed at gay men who liked to play at being stereotypical butch bikers. Or indeed, surprised when Halford came out as homosexual himself in 1998. Titles like ‘Hell Bent for Leather’ didn’t take too much decoding in order to detect a possible gay subtext.

In truth, powerful custom bikes have long been largely the stuff of fantasy for many young metal fans, alongside other iconic imagery, from battleaxes and expensive guitars, to demons and improbably chesty ladies-of-easy-virtue. Romantic escapism has always been at the core of the subculture’s allure. Few worldly fans were surprised when it became clear that the band’s wardrobe came, not from a Hell’s Angels chop shop, but an S/M boutique aimed at gay men who liked to play at being stereotypical butch bikers. Or indeed, surprised when Halford came out as homosexual himself in 1998. Titles like ‘Hell Bent for Leather’ didn’t take too much decoding in order to detect a possible gay subtext.

This isn’t, incidentally to suggest heavy metal is an inherently homosexual subculture, rather that both cultures share a keen appreciation of the subtleties of high camp. There are gay metal aficionados, but one suspects no more or less in number than in any comparable demographic. And, contrary to the enduring negative stereotypes about metal fans as backward bigots, Rob Halford recalls that when he revealed his sexuality to fans, ‘the vast majority of them were completely accepting of me, and it was tremendously powerful.’ Metal’s long provided a home to outcasts and misfits – though typically those beyond the clichéd ‘minorities’ patronisingly put on pedestals by the liberal left.

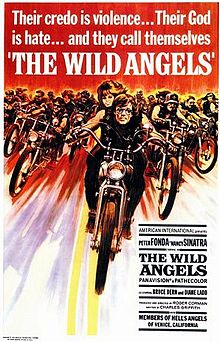

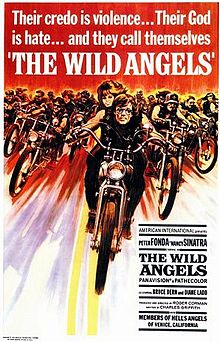

Returning back to ‘Easy Rider’, it’s worth making a few observations on the 1969 film’s subcultural significance. Its importance rests in part on the way the movie represented an axis between a series of underground trends and movements. It wasn’t, as many suppose, the first cult biker film. By the time ‘Easy Rider’ hit the screens, a subgenre had already been established for several years. Movies like ‘The Wild Angels’ (1966), ‘Hell’s Angels on Wheels’ (1967), ‘Angels from Hell’ (1968) were already pulling crowds and outraging critics with their depiction of high-octane, two-wheeled mayhem and sleazy, nihilistic thrill-seeking. The tag-lines for these films – such as ‘Their credo is violence… Their God is hate…’ for ‘The Wild Angels’ – could easily fit into a metal lyric of some kind.

Returning back to ‘Easy Rider’, it’s worth making a few observations on the 1969 film’s subcultural significance. Its importance rests in part on the way the movie represented an axis between a series of underground trends and movements. It wasn’t, as many suppose, the first cult biker film. By the time ‘Easy Rider’ hit the screens, a subgenre had already been established for several years. Movies like ‘The Wild Angels’ (1966), ‘Hell’s Angels on Wheels’ (1967), ‘Angels from Hell’ (1968) were already pulling crowds and outraging critics with their depiction of high-octane, two-wheeled mayhem and sleazy, nihilistic thrill-seeking. The tag-lines for these films – such as ‘Their credo is violence… Their God is hate…’ for ‘The Wild Angels’ – could easily fit into a metal lyric of some kind.

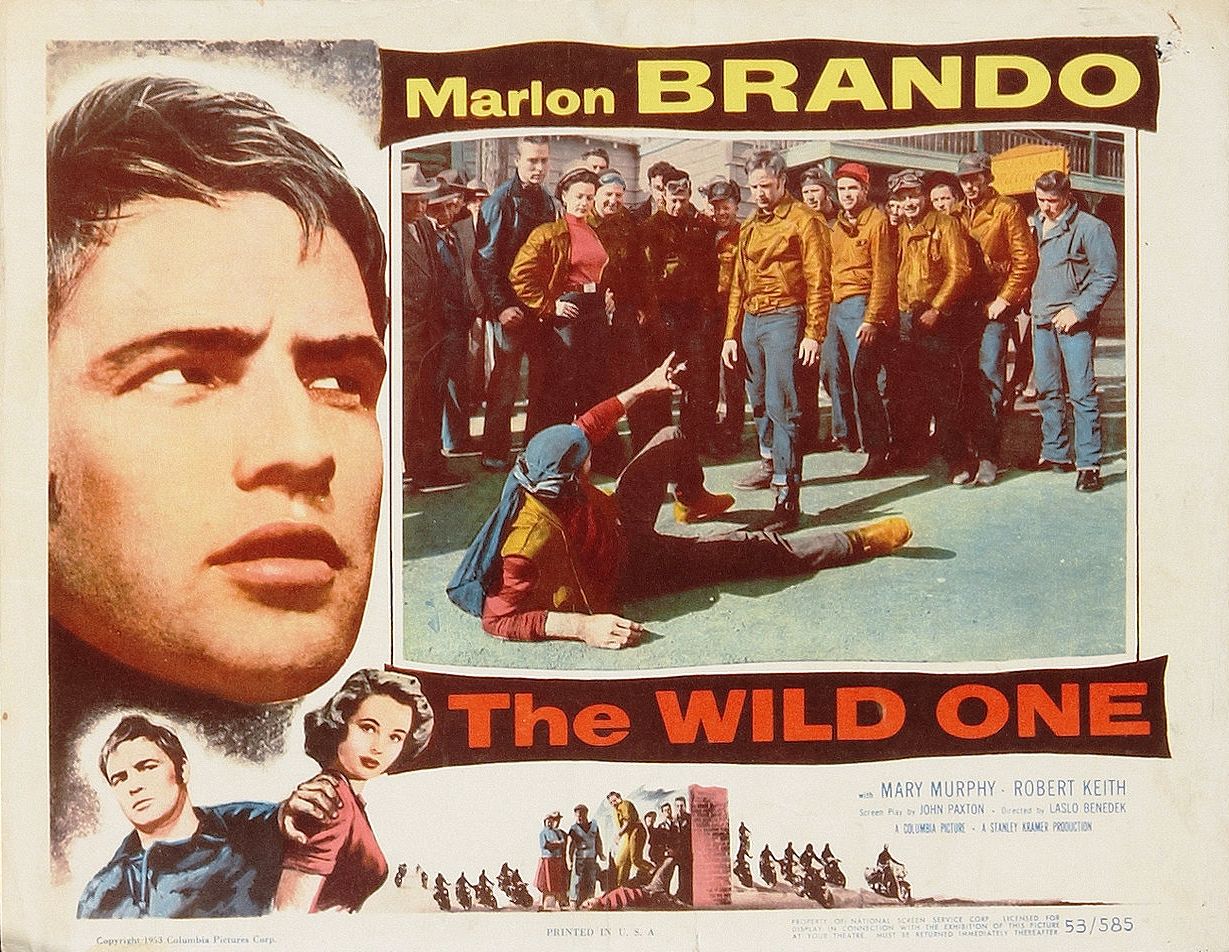

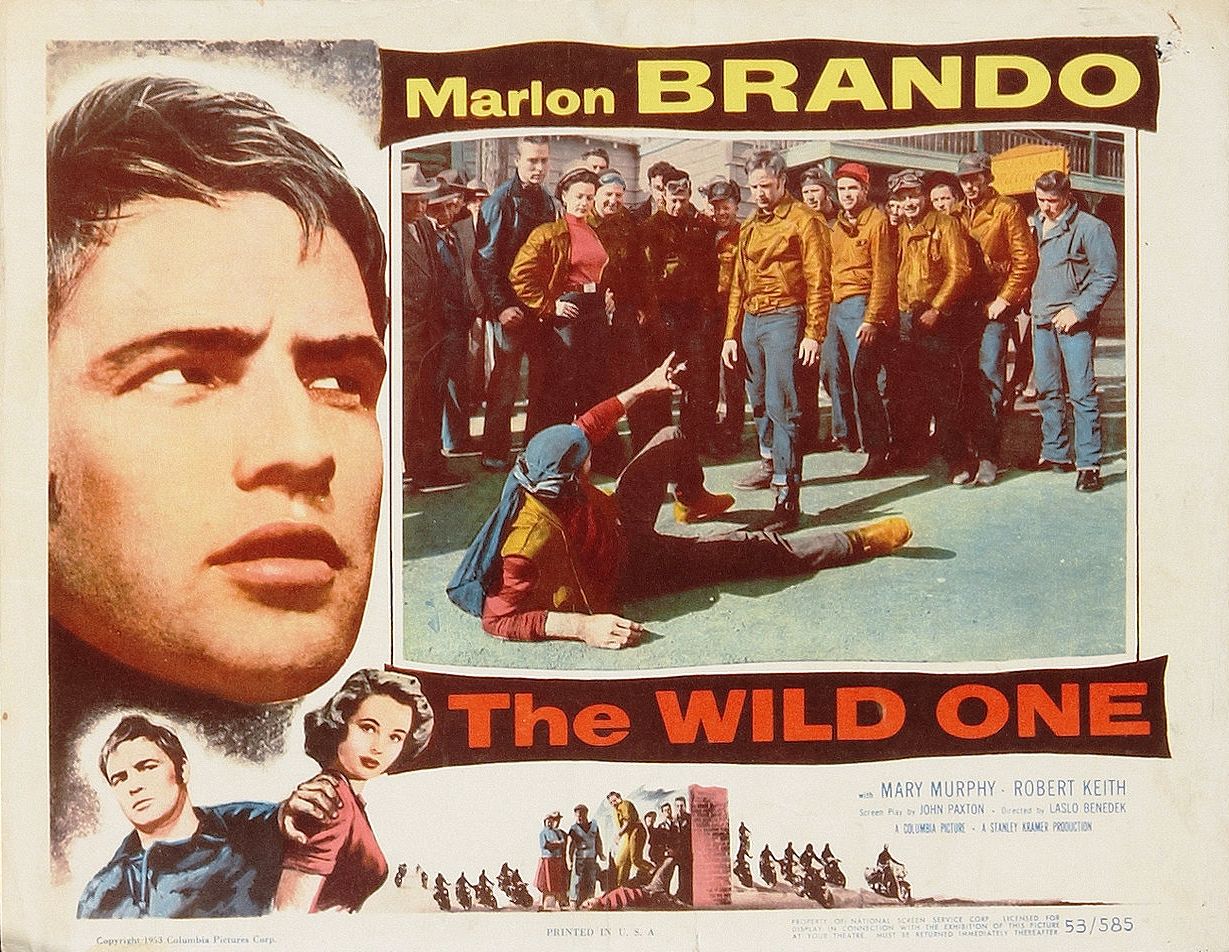

By way of comparison, ‘Easy Rider’ is a gentle, even pacifistic ride, where the protagonists are the victims, not the perpetrators of brutality. Our heroes may have financed their journey of discovery with a sizeable drugs deal, and chosen to take it astride chopped Harleys, but their goal is the pursuit of old-fashioned freedom in the face of an oppressive world. While the Hells Angels themselves only came to prominence in the 60s – largely courtesy of demonisation in the media – the outlaw biker culture depicted in the Angel films had roots stretching at least as far back as the 40s. The 1953 film ‘The Wild One’, which both launched the career of a young Marlon Brando and a legion of leather-clad, rebel motorcyclists, was inspired by a 1947 bike rally in Hollister, California, that famously got out of hand.

‘The Wild One’ was a subcultural game-changer, and so was ‘Easy Rider’ sixteen years later. Interestingly, colourised stills from the B&W ‘Wild One’ depict the bikers’ jackets as brown, not black, while they ride Brit bikes rather than American Harleys (then often considered the cheap, unreliable option). Bikers had long been condemned by straights for their longhair, but such things are relative. In the early days, when crew cuts and buzz cuts signified male conformity, hair that approached the collar was regarded with suspicion, particularly if greased up into a quiff or pompadour. It was ‘Easy Rider’, with its international success, which was instrumental in introducing even longer hair into the metal scene, via the outlaw biker subculture.

‘The Wild One’ was a subcultural game-changer, and so was ‘Easy Rider’ sixteen years later. Interestingly, colourised stills from the B&W ‘Wild One’ depict the bikers’ jackets as brown, not black, while they ride Brit bikes rather than American Harleys (then often considered the cheap, unreliable option). Bikers had long been condemned by straights for their longhair, but such things are relative. In the early days, when crew cuts and buzz cuts signified male conformity, hair that approached the collar was regarded with suspicion, particularly if greased up into a quiff or pompadour. It was ‘Easy Rider’, with its international success, which was instrumental in introducing even longer hair into the metal scene, via the outlaw biker subculture.

‘Easy Rider’ represented a collision between the biker and hippie subcultures, already cross-pollinating in the heady atmosphere of America’s West Coast. Previously a world chiefly fuelled by beer, the introduction of illicit narcotics to the mix – at least according to their many critics – transformed the hardcore of the biker legions from lawless hellraisers to organised crime outfits. In fact, clubs like the Hell’s Angels had long been far more ordered, even disciplined, than many outsiders suspected, working under a rigidly enforced set of rules. This chimes ill with heavy metal’s instinctive rejection of rules, which is perhaps why ‘Easy Rider’ – with its underlying requiem for doomed freedom and individualism – is more a part of metal’s blueprint than the brutal Angel movies with their close-knit cabals of freewheeling thugs and hard-drinking ne’er-do-wells.

‘Easy Rider’ was in many respects a tombstone for the hippie era (the subculture’s forefathers had held a funeral for the movement in its San Francisco birthplace two years earlier). The film’s bleak ending expressed a general sense that the experiment in Flower Power idealism had failed, one of a series of grim omens in 1969 that promised a dark future ahead. Things were definitely getting heavy. Early heavy metal provided a funeral dirge for the lost innocence of the love generation. Black Sabbath often talked about the contrast between the beautiful things they’d heard were happening in sunny California, and the altogether grimmer realities they were experiencing, a sense of despair and betrayal that characterised their early music. Heavy metal was the epic hangover after the hedonistic celebrations of the Summer of Love.

‘Easy Rider’ was in many respects a tombstone for the hippie era (the subculture’s forefathers had held a funeral for the movement in its San Francisco birthplace two years earlier). The film’s bleak ending expressed a general sense that the experiment in Flower Power idealism had failed, one of a series of grim omens in 1969 that promised a dark future ahead. Things were definitely getting heavy. Early heavy metal provided a funeral dirge for the lost innocence of the love generation. Black Sabbath often talked about the contrast between the beautiful things they’d heard were happening in sunny California, and the altogether grimmer realities they were experiencing, a sense of despair and betrayal that characterised their early music. Heavy metal was the epic hangover after the hedonistic celebrations of the Summer of Love.

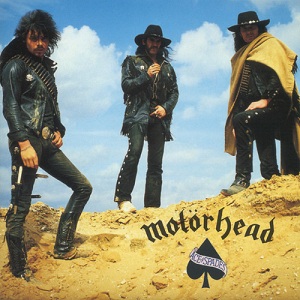

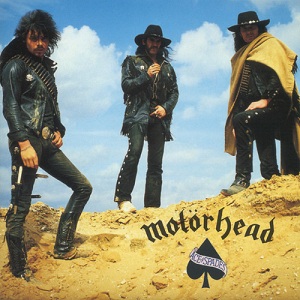

While heavy metal finding its feet during the 70s, it drew on a few hippie influences, and rather more drawn from biker culture, such as black leather and cut off denim jackets. However other elements began to creep in. For example, one of the most influential heavy albums ever recorded, is surely Motörhead’s 1980 release ‘Ace of Spades’ (despite the band’s rejection of the metal label). Not just for its seminal musical content, but also the photo shoot on the cover, which depicts the band as desperados drawn straight from a Spaghetti Western. I’d contend that shoot would never have happened without the huge success of Sergio Leone’s ‘Dollars’ trilogy of films released some fifteen years earlier. Clint Eastwood’s snake-eyed, lone wolf Man With No Name made a perfect heavy metal icon, and cowboy boots and bullet belts duly made their way into metal wardrobes (though not many could pull off the poncho).

You’ll have noticed by now that I’ve been emphasising general culture – cinema in particular in this case – in my survey of the roots of heavy metal. It’s more conventional to focus almost exclusively on music while attempting such a survey – something I’ve deliberately avoided here. It’s always been a feature of my work to try and understand the milieu in which subcultures avoid – they do not evolve in a vacuum, but react to events and other cultural output that is going on around them. Yet I can’t deny that the music is, of course, highly significant. In the second half of this essay, I’m going to address where heavy metal music came from in my opinion. My theories don’t agree with the orthodox version, and might just surprise a few of you…

You’ll have noticed by now that I’ve been emphasising general culture – cinema in particular in this case – in my survey of the roots of heavy metal. It’s more conventional to focus almost exclusively on music while attempting such a survey – something I’ve deliberately avoided here. It’s always been a feature of my work to try and understand the milieu in which subcultures avoid – they do not evolve in a vacuum, but react to events and other cultural output that is going on around them. Yet I can’t deny that the music is, of course, highly significant. In the second half of this essay, I’m going to address where heavy metal music came from in my opinion. My theories don’t agree with the orthodox version, and might just surprise a few of you…