While Street Culture, my book on the history of subculture sits patiently in the wings awaiting publication, I was recently approached by the editors of Kulturaustausch who were interested in me penning a piece on a similar subject. The magazine is a quarterly publication, dealing with politics, culture and society, published by Germany’s Institute of Foreign Affairs. http://www.ifa.de/pub/kulturaustausch/ They have an issue focusing on death coming up, and asked me to write a short piece discussing death and counterculture. It’s a wide subject, so I inevitably had to cut the original feature down to fit the limited space available. However, they were kind enough to give me permission to publish the longer version of the essay here, for the benefit of anyone interested in the unedited original, particularly for those of us whose German is too rusty to be able to appreicate the printed version in Kulturaustausch.

I hope some of you find this little survey of death and subculture diverting…

DEAD COOL – MORBIDITY & MORTALITY IN MODERN SUBCULTURE

(c) Gavin Baddeley

Counterculture tribes or street subcultures employ a bewildering array of symbols – from Egyptian ankhs to the (A) anarchy sign – as tattoos, T-shirts, jewellery, album art and graffiti. None is more ubiquitous – or open to misinterpretation – than the skull. The ancient, universal icon of death, it is just one example of the morbid themes and iconography common in modern subculture. But what does this relationship with death imply? Is it, as some religious reactionaries and rightwingers insist, suggestive of a tendency to suicide or homicide? Or, as counterculture’s liberal critics are apt to sneer, simply adolescent attention seeking? Might there be, however, something older and more interesting behind countercultural morbidity?…

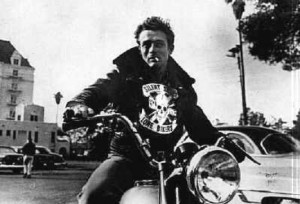

The counterculture sprang into life in the years following the Second World War, when economic affluence created a new demographic – the teenager – ripe for exploitation by entrepreneurs and to serve as a scapegoat by social conservatives. Hollywood was quick off the mark with films hoping to please both perspectives, focusing on the new buzzwords of ‘juvenile delinquency’. Among the first such films was the 1949 thriller Knock on Any Door, whose adolescent hoodlum antihero – defended by Humphrey Bogart as a hard-bitten attorney – coined the immortal lines ‘Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse’, which one critic later described as a ‘clarion call for a generation of disenfranchised youth’. The film’s director, Nicholas Ray, went on to direct the classic of the juvenile delinquency subgenre six years later, starring an actor who became indelibly associated with the sentiment, even if he never spoke the lines in his brief career.

The film was Rebel Without a Cause, the actor of course James Dean, whose portrayal of the tormented teen Jim Stark immortalised him as the archetypal cool young outcast. Throughout the film Jim courts death, only narrowly escaping being shot by the police in the downbeat finale. The idea of suicide as a consequence of adolescent angst is an enduring riff. And an old one. One of the archetypal images of Romanticism is the 1856 painting The Death of Chatterton, depicting the brilliant poet Thomas Chatterton, who took his own life at just 17 years-of-age in 1770. It is the main subject of perhaps the greatest play ever written, Shakespeare’s Hamlet (c.1600) whose titular antihero is the original brooding blackclad youth, itself based upon a 13th century Danish history book. While Jim Stark survived Rebel Without a Cause, James Dean died in a car accident a month before its release, freezing him forever as an eternal adolescent.

The film was Rebel Without a Cause, the actor of course James Dean, whose portrayal of the tormented teen Jim Stark immortalised him as the archetypal cool young outcast. Throughout the film Jim courts death, only narrowly escaping being shot by the police in the downbeat finale. The idea of suicide as a consequence of adolescent angst is an enduring riff. And an old one. One of the archetypal images of Romanticism is the 1856 painting The Death of Chatterton, depicting the brilliant poet Thomas Chatterton, who took his own life at just 17 years-of-age in 1770. It is the main subject of perhaps the greatest play ever written, Shakespeare’s Hamlet (c.1600) whose titular antihero is the original brooding blackclad youth, itself based upon a 13th century Danish history book. While Jim Stark survived Rebel Without a Cause, James Dean died in a car accident a month before its release, freezing him forever as an eternal adolescent.

While Dean died behind the wheel of his sportscar, he was also a keen motorcyclist, and the motorbike quickly became an icon of youth rebellion as potent as the quiff or electric guitar. Dedicated young daredevil bikers quickly adopted death symbolism, most notably the skull and crossbones, on their funereal black leathers. It’s a statement of cavalier courage – that the rider was comfortable with death – tempered perhaps by a superstitious hope that Death might look kindly upon those bearing his colours. The skull and crossbones motif has been adopted for similar reasons by numerous military regiments, often accompanied by the motto ‘death or glory’. Significantly, most were cavalry units – hussars and lancers – arrogant young horsemen who cultivated the same dashing image and craved the same thrills of speed and danger that captivated the Rockers. Generations of generals have relied upon the same youthful illusion of immortality that drives today’s reckless Bikers to fill the ranks of their regiments.

The famous association between the skull and crossbones and pirates is also relevant here. Long before anarchy was formulated as a political philosophy, buccaneers and privateers were living the life afloat and in pirate strongholds like Port Royal. In addition to the skull and crossbones, the Jolly Roger standard also sometimes incorporated devils, bleeding hearts and hourglasses. According to the historian Marcus Rediker pirates used taboo imagery to affirm ‘their unity symbolically’, and that such macabre ‘interlocking symbols – death, violence, limited time – simultaneously pointed to meaningful parts of the seaman’s experience, and eloquently bespoke the pirates’ own consciousness of themselves as preyed upon in turn.’ Many modern subcultures – Punks, Bikers, Metalheads, Psychobillies and such – adopt similar imagery for analagous reasons. Sporting taboo motifs strengthens the bonds among a group of outcasts, while having a defensive effect by suggesting fearlessness and menace to outsiders.

The most famous rivals of the UK’s motorcycling Rockers in the early-Sixties were the scooter-mounted Mods, who prefer their speed in pill form. While they eschew death imagery, even the style-obsessed Mods have some connections. The subculture’s unofficial anthem is ‘My Generation’ (1965), featuring the immortal line ‘Hope I die before I get old’ – a typical Mod expression of extreme vanity, seeing middle age as literally a fate-worse-than-death. The line’s inevitably returned to haunt the band. When they played the number as the finale to the recent Olympic Closing Ceremony, only their drummer, Keith Moon had lived up to the song’s rash aspiration, dead of a drugs overdose in 1978. An archetypal hellraiser, ‘Moon the Loon’ is just one of a gallery of subculture icons who have made the ultimate sacrifice, dying rather than abandon the subculture’s reckless lifestyle. His last words were reputed to have been ‘If you don’t like it, you can just fuck off!’

On the surface, the Hippies, with their peace and love credo, are even more improbable aficionados of morbidity, preferring such exotic notions as reincarnation. Yet they gave us bands with names like the Grateful Dead (who took their name from a macabre European folk tale), and gloomy songs like ‘The End’ and the ‘I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die-Rag’. The former song – a morbid, somewhat surreal, meditation on loss from 1967 – was by the Doors who explored the darkest fringes of the psychedelic spectrum, proving that all was not sweetness and light among the Flower Children. The ‘I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-To-Die-Rag’ (1965) by Country Joe and the Fish, became one of the leading anti-Vietnam War songs of the era, a sardonic, satirical number they famously played at the Woodstock Festival in August of 1969. For the Hippies, death was metaphorical, metaphysical, and political.

By 1969 Hippie optimism had largely expired, and leading the funeral dirge from England’s gloomy industrial Midlands was Black Sabbath, now recognised as the first Heavy Metal band. Death loomed large on Sabbath’s bleak horizon. Songs like ‘Electric Funeral’ are threnodies to a world destined to perish under a nuclear holocaust, while tracks like ‘Hand of Doom’ focussed on the awful fate that awaited an individual who had tried to escape the horrors of the outside world with drugs. Historical or fanastic escapism, frequently with morbid or violent overtones, is a recurring Metal riff. The definitive example is perhaps ‘The Trooper’ (1983) by Iron Maiden. It’s inspired by the famous Charge of the Light Brigade of 1854, when a British cavalry force made a heroic but suicidal attack in the Crimean War, led by the 17th Lancers, a regiment with the ‘death or glory’ motto. Battle is a dominant theme in Heavy Metal, but the prevailing story is one of doomed heroism, the Romantic vision of the warrior falling before overwhelming odds.

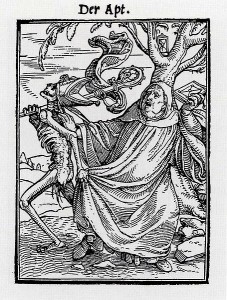

A popular fantasy figure in Metal and kindred subcultures is the Grim Reaper, the personifaction of death drawn from medieval folkore. The scythe-wielding Reaper was particularly popular among the medieval common populace in his role as the Great Leveller – personification of the idea that nobody can escape death – that death makes no distinction between peasant and prince, or pauper and pope. The idea that privilege and status dissolve before the Reaper remain’s a source of grim satisfaction – even black humour – for those who feel excluded by society. Another afiliated death tradition with modern subcultural resonance is that of memento mori. If one of our medieval ancestors saw a skull, scythe or suchlike in art or masonry, they wouldn’t interpret it as a celebration of death, but an admonition to live your life to the full because none of us are immortal. Many insiders would defend the morbid themes and imagery in subculture in similar terms – that an awareness of death is a powerful incentive to appreciate life.

A popular fantasy figure in Metal and kindred subcultures is the Grim Reaper, the personifaction of death drawn from medieval folkore. The scythe-wielding Reaper was particularly popular among the medieval common populace in his role as the Great Leveller – personification of the idea that nobody can escape death – that death makes no distinction between peasant and prince, or pauper and pope. The idea that privilege and status dissolve before the Reaper remain’s a source of grim satisfaction – even black humour – for those who feel excluded by society. Another afiliated death tradition with modern subcultural resonance is that of memento mori. If one of our medieval ancestors saw a skull, scythe or suchlike in art or masonry, they wouldn’t interpret it as a celebration of death, but an admonition to live your life to the full because none of us are immortal. Many insiders would defend the morbid themes and imagery in subculture in similar terms – that an awareness of death is a powerful incentive to appreciate life.

No subcultures is as heavily associated with death as the theatrical offshoot of Punk, initially known as Deathrock in the US and Goth in Europe. There are essentially two attitudes to death in Goth, exemplified in Britain by Bauhaus and Joy Division, and 45 Grave and Christian Death in America. Bauhaus are widely credited with releasing the first Goth recording, the 1979 EP ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’. Bela Lugosi is the film actor who became famous for playing Dracula in 1931, and the song is essentially a spooky mood piece, calculated to appeal to fans of vintage horror. 45 Grave are also purveyors of somewhat camp, ghoulish fun, the tenor of the band’s gleefully sick humour evident in their lead singer’s stagename Dinah Cancer. By way of contrast, there is no gallows humour in the dark, bleak, experimental rock of either Joy Division or Christian Death. Indeed the authenticity of the suicidal despair that defined the music was underlined when both band’s lead singers hung themselves – Ian Curtis of Joy Division in 1980, Christian Death’s Rozz Williams 18 years later.

No subcultures is as heavily associated with death as the theatrical offshoot of Punk, initially known as Deathrock in the US and Goth in Europe. There are essentially two attitudes to death in Goth, exemplified in Britain by Bauhaus and Joy Division, and 45 Grave and Christian Death in America. Bauhaus are widely credited with releasing the first Goth recording, the 1979 EP ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’. Bela Lugosi is the film actor who became famous for playing Dracula in 1931, and the song is essentially a spooky mood piece, calculated to appeal to fans of vintage horror. 45 Grave are also purveyors of somewhat camp, ghoulish fun, the tenor of the band’s gleefully sick humour evident in their lead singer’s stagename Dinah Cancer. By way of contrast, there is no gallows humour in the dark, bleak, experimental rock of either Joy Division or Christian Death. Indeed the authenticity of the suicidal despair that defined the music was underlined when both band’s lead singers hung themselves – Ian Curtis of Joy Division in 1980, Christian Death’s Rozz Williams 18 years later.

Such tragedies give weight to those who accuse subcultures of feeding unhealthy morbidity, even branding them teen suicide cults. Yet these are extreme, and happily rare examples, and both men had serious issues – Curtis’s depression fed by chronic ill health, Williams plagued by a heroin habit – problems they naturally addressed in their art. If we are to censure sad music, then we must strike everything from ‘Eleanor Rigby’ by the Beatles to Tchaikovsky’s ‘Symphony Number 6’ from our collective playlists. Sometimes, for those plagued by depression, the melancholy sound of a kindred soul can be the only meaningful therapy. Sincere, sad music can provide powerful catharsis. In recent years Emo has threatened to eclipse Goth as the favourite target for subcultural critics. In 2008, the suicide of a thirteen-year-old English girl triggered a crusade in the UK press, the rightwing paper the Dail Mail running headlines like ‘Why No Child is Safe From the Sinister Cult of Emo’, focusing on the teen’s love of bands like My Chemical Romance as the cause of the tragedy.

Some leapt to the defence of My Chemical Romance and the Emo subculture. ‘For the majority of fans, emo music acts like a release valve, driving away all the negative energy and emotion inside them,’ observed the media and popular culture lecturer Dr Dan Laughey. Vikki Bourne attended a protest against the anti-Emo stories in the press with her daughter Kayleigh, 15, saying they were both huge fans of My Chemical Romance and enjoyed a closer relationship as a result. ‘Emos are being portrayed as self-harming and suicidal and miserable and they’re not,’ said Vikki. ‘Since my daughter met the friends she’s got, she’s happy, she’s got a social life, she’s not suicidal, she’s got confidence.’ A Scottish study on attempted suicide and self-harm among teens conducted the following year, did find a higher incidence among Goths. Robert Young, one of the researchers involved, observed that ‘since our study found that more reported self-harm before, rather than after, becoming a Goth, this suggests that young people with a tendency to self-harm are attracted to the Goth subculture. Rather than posing a risk, it’s also possible that by belonging to this subculture young people are gaining valuable social and emotional support from their peers.’

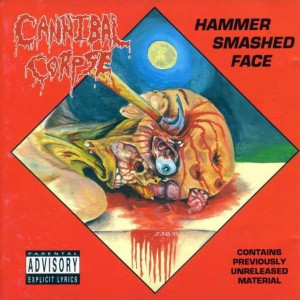

Perhaps the most exuberantly macabre subculture, and hence most difficult for outsiders to comprehend, is Death Metal. Its imagery and lyrics are dominated by violent death and post mortem putrefaction – ‘Hammer Smashed Face’ by Cannibal Corpse and ‘Regurgitated Guts’ by Death are typical song titles. In many respects the attraction is the same as that of gory horror films, though that begs the question of why those appeal to a similar audience. The desire to almost literally wallow in the grisly viscera of human mortality is partly simply the pleasure of shocking outsiders, while showing that you can take – even enjoy – such imaginary butchery. There’s also a lot more humour involved than often appreciated – of a sick joke taking something so far beyond the realms of good taste as to be absurd. Gallows humour is also an age-old way of coping with the fear of injury and death – of using familiarity to pull the sharp teeth from the Reaper’s rictus grin.

This use of humour to diminish worries is, of course, an almost universal human characteristic. It’s just that Death Metal takes it further. Most of the attitudes to death discussed in this article can be found in less extreme forms in mainstream culture. Death is endemic in the mainstream media – from TV cop shows and war films to news reports on disasters – though the emphasis is usually on dying or killing as opposed to on death itself. While our ancestors were familiar with death courtesy of high mortality rates from infancy onwards, slaughtering their own livestock, open-casket funerals, and so forth, today we have largely isolated ourselves from the realities of death. It has become something of a dirty secret, and outsiders – not least members of subcultures – have a tendency to relish airing dirty secrets. A comfortable relationship with taboos like death helps distinguish outlaws and outcasts from conventional culture, while helping to maintain a healthy society by acting as a constant reminder that we can’t simply brush things that make us uncomfortable under the carpet.

This use of humour to diminish worries is, of course, an almost universal human characteristic. It’s just that Death Metal takes it further. Most of the attitudes to death discussed in this article can be found in less extreme forms in mainstream culture. Death is endemic in the mainstream media – from TV cop shows and war films to news reports on disasters – though the emphasis is usually on dying or killing as opposed to on death itself. While our ancestors were familiar with death courtesy of high mortality rates from infancy onwards, slaughtering their own livestock, open-casket funerals, and so forth, today we have largely isolated ourselves from the realities of death. It has become something of a dirty secret, and outsiders – not least members of subcultures – have a tendency to relish airing dirty secrets. A comfortable relationship with taboos like death helps distinguish outlaws and outcasts from conventional culture, while helping to maintain a healthy society by acting as a constant reminder that we can’t simply brush things that make us uncomfortable under the carpet.