It isn’t always easy being an author. I mean it’s not tough in the same way as, say, saving old ladies from a burning building or working the late shift at A&E on a Saturday night for a living. But we do all have our crosses to bear (even if some us prefer to carry them inverted). On this particular occasion, I thought I’d have an unattractively self-indulgent whine about the problems with getting anything vaguely original published. It’s a particular issue at the moment, as the reflex response to the harsh economic climate from many publishers and editors is to pull their heads in and only print the most conservative material they can find. For somebody who likes to write (and read) something a little different, this can be problematic.

I thought I’d offer a concrete example in the shape of a profile rejected from my recent book Vampire Lovers. Most books – indeed most creative endeavours – are conceived with compromise. This is usually healthy. The confident hand of a skilled, sympathetic editor almost invariably improves a book or article. (I talked about this in my previous rumination ‘Does Size Matter?‘ http://www.gavinbaddeley.com/archives/380) However, there is a balance to be struck, and it is frustrating when the direction of a magazine article or book is unduly compromised by the demands of a – frequently illusory – lucrative target audience. Vampire Lovers was overtly born from a compromise. My publisher thought Twilight made vampires a commercial proposition, while I’m interested in the undead, and thought I could do something worthwhile with the subject matter, including profiles of TV and cinema’s leading bloodsucking sex symbols, leavened with ruminations on what made them appealing.

I confess that I’m not a fan of Twilight, but I do think it’s interesting as phenomenon, and could certainly get my teeth into that. The idea was to balance the profiles between male and female, and cult and popular subjects, to create a book I felt was well-rounded and potentially entertaining to a wide audience. However, I reached a deadlock with the publisher. They insisted I include someone from The Vampire Diaries TV show, and drop one of the cultier old entries to accomodate it. I could find nothing interesting – or indeed nice – to say about the series which simply seemed a cynical crossbreed of the crassest components of Twilight and True Blood. Moreover, I didn’t want to lose any of my original cast of oddball bloodsuckers which I felt helped give the book character and depth. As anyone who owns a copy of the book can attest, I lost this particular struggle.

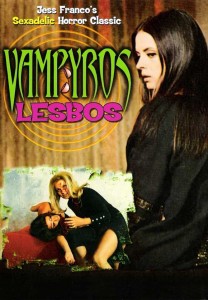

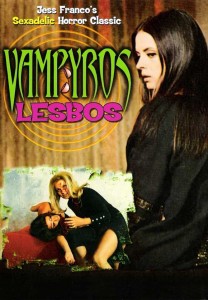

It was particularly depressing that the entry that hit the cutting room floor was the gorgeous Soledad Miranda in her mesmeric performance in Vampyros Lesbos, perhaps the definitive cult vamp flick. I like to think the reviews bore me out. Most were very positive but a couple expressed a desire to see more female entries and a greater emphasis on cult classics than recent Twilight cash-ins. I reread parts of the book recently, and I’m broadly pleased with it – unlike the vast majority of recent bandwagon-jumping, undead pulp, Vampire Lovers was written by a true lifelong fan, and I think it shows. I still, however, wish Soledad had stayed and that I’d never heard of the Vampire Diaries, and because it seems a shame to waste the essay on Vampyros Lesbos I’m posting it here. (If you own a copy of Vampire Lovers, please feel free to tear out the section on The Vampire Diaries, print this out, and crudely glue it in its place.)

“A Psycho-Sexadelic Horror Freakout!”

Soledad Miranda

as

Countess Nadine Carody

in

Vampyros Lesbos

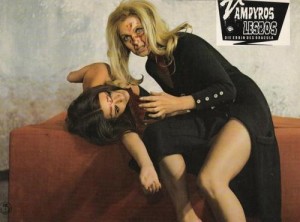

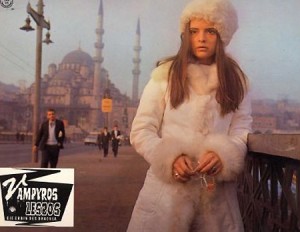

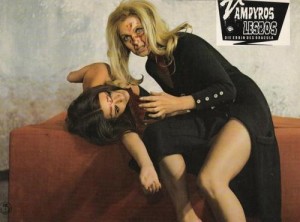

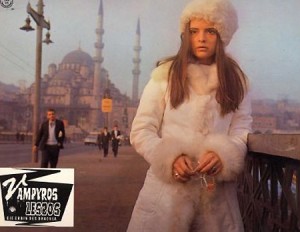

Just what qualifies as a true cult movie? How about a sexually-charged, subtitled Spanish-German vampire movie, set in Istanbul, about a foxy Hispanic, man-hating vampire lesbian? Our gorgeous Sapphic bloodsucker, one Countess Carody, moonlights as a surreal stripper in a seedy Turkish cabaret club. By day, she doesn’t sleep in a coffin, but likes to sunbathe nude in front of her beachside apartment, itself a testament to the most lurid interior design chic of its day, a pad so tacky it travels round the clock to become cool. The same 70s hipster style is evident among the cast – chicks in peekaboo negligees and thick false eyelashes, guys in big tinted specs and heavy sideburns. Add an appropriate soundtrack – all swirling Hammond organ, funked up sitar and a breathy voice whispering “Ecstasy” – and, if anything, the 1970 movie Vampyros Lesbos seems almost over-qualified in the cult department.

One prerequisite of cult status in cinematic terms is the ability to divide critics and audiences, and Vampyros Lesbos certainly does that. While most cineastes turn their noses up at a film widely dismissed as a crass monument to technical ineptitude and lurid bad taste, to fans it is a bizarre tour de force, perhaps the masterpiece of the man responsible, Spanish filmmaker Jess Franco. It’s undeniably Franco’s vision at work here. He not only directed and wrote, but also takes a supporting role in Vampyros Lesbos, as the sleazy hotel clerk Memmet, a psychosexual sadist, sent over the edge when his wife falls victim to the charms of Countess Carody. If not one of the world’s most acclaimed filmmakers, Jess is surely one of the busiest. Franco has over 150 directing credits to his name, though an exact total is difficult to come by, as his films frequently appear with varying titles, in numerous versions (Vampyros Lesbos has been released under at least a dozen different names, from The Heritage of Dracula to The Vampire Women).

Devotees can immediately identify Vampyros Lesbos film as their idol’s work under any title, as it contains so many of the inimitable characteristics of a Franco film, though whether this reflects a unique vision, or is simply the inevitable consequence of making so many films so quickly is open to debate. There is plenty of handheld camerawork, leading to both interesting angles and unsteady frames, while zoom shots – so frequent in some Franco films as to seem close to a nervous compulsion – are in evidence. The small crew is multi-national, as is the cast, adding to a strange aura of exoticism and chaos that characterises classic Franco, the multi-lingual Spaniard habitually filming under conditions most directors would consider creative suicide. Film shares a place in the director’s affections with a lifelong passion for jazz, and fans have compared his unruly style of filmmaking with the unpredictable, improvisational qualities of freeform jazz. Jazz scores are also a Franco trademark – frequently composed by Jess himself – and the soundtrack to Vampyros Lesbos, released under the subtitle ‘Sexadelic Dance Party’, enjoys a cult following in its own right.

“Men still disgust me. Many were captivated by me. Many women. I bewitched them. They lost their identity, I became them. But then I met Linda. Now I’m under her spell.”

Sex is also key to his celluloid recipe, and no Franco film is complete without a lengthy scene lingering on (or zooming into) a nubile nymphet, writhing in an orgasmic reverie on the floor. On writhing duties in Vampyros Lesbos is the Spanish actress Soledad Miranda as Countess Nadine Carody. The Countess had an encounter with Count Dracula himself, who she explains rescued her from a rapist. She walked away from the experience as a vampire with a disdainful contempt for men, while the Count fell under Nadine’s erotic spell. “He was addicted to my body”, she explains. In Vampyros Lesbos we follow the progress of a blonde estate agent named Linda, who has been having erotic nightmares about Nadine, and is assigned to settle Dracula’s inheritance. It turns out, of course, that the chief beneficiary of the Count’s estate is the haunting brunette of her torrid dreams, and Linda’s supernatural seduction begins in earnest. In many respects, this makes Vampyros Lesbos an erotic adaptation of the original Dracula, though one of the most unorthodox ever filmed, replacing most of the Victorian novel’s principle male characters with sexually liberated ladies.

This wasn’t Franco’s first take on Bram Stoker’s famous book. As already noted in our piece on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the Spaniard had previously made a version which, like Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 epic, was sold as a faithful adaptation of Stoker’s original novel. It was a dubious claim, but sufficient to convince a reluctant Christopher Lee – the saturnine English actor who had become an international star playing the Count for Hammer studios, but had sworn to renounce the part – to don the midnight cape once more. Franco’s Count Dracula also featured Soledad Miranda in her first major role for the director, as the Count’s victim, Lucy Westenra. “The normally reticent Lee waxed poetic about the sheer chemistry of this naturally poised beauty”, according to authors Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs in Immoral Tales, their classic study of cult European horror cinema. “During filming they had to retake the neck-biting scene over two dozen times, and even after twenty or thirty takes he still felt goosebumps and shivered with the natural electricity during every take. She had the X ingredient, that indefinable quality that could have made her a star.”

It’s a story that has all the hallmarks of a horror movie myth. Not least, some cynics might contend, because the idea of a famously fast operator like Franco allowing dozens of takes of any scene seems singularly improbable. But the brief partnership between Jess Franco and Soledad Miranda invites cinematic myth. As the past tense employed in the above quote implies, Soledad never enjoyed stardom – even the cult stardom conferred by films like Vampyros Lesbos – as she tragically died in a car accident, just weeks after Vampyros Lesbos premiered. The Spanish actress died on her way to sign an important new contract that may have paved the way for the international recognition that had thus far eluded her. Soledad Miranda was already something of a celebrity in her homeland, courtesy of a string of film and TV credits. But Spain was still under the dictatorship of Jess’s namesake General Francisco Franco, who imposed stringent media censorship, and Spanish celebrity seldom meant much abroad.

Soledad made several films with Jess Franco, though she mostly used the name Susann Korda or Susan Korday in the credits, as such sexually provocative roles invited condemnation in the socially conservative Spain of the day. Ironically, many of Jess Franco’s films were banned in Francoist Spain. The director told Amy Brown, curator of Sublime Soledad, an on-line shrine to the actress, “the films she made with me from Dracula on, were the films that the Spanish audience didn’t know! They haven’t seen it. Because the film was forbidden by the Spanish censorship…” Franco (from hereon in, Jess, not General) has always been fulsome in his praise for his most famous leading lady. “I thought she was fantastic and everybody in the crew said, ‘Oh, my God, she’s wonderful, she’s perfect’”, he told leading cult film expert Tim Lucas. “I think Soledad was fantastic in my Dracula. Even Christopher was very impressed.”

In common with all great cult stars, Soledad Miranda’s screen presence encapsulated something – in her case something powerfully erotic – that is devilishly difficult to capture with words. Jess Franco suggested to Tim Lucas that she “seemed to come fully to life only on camera.” Franco elaborates that she “had a personality which translated to the screen a lot of the things that she felt deep inside. But it translated in an unconscious way. She was a funnel. It was very simple for me to explain things to her. She got it immediately because she was like a funnel. I think she had this special thing that the stars have. It’s not that you have to be a great actor but when this actor enters the scene you don’t look at anybody else – you only look at this girl or this guy. And she had this. She was a very sweet and very nice person… It happened very often with the Spanish gypsy people… Those gypsies had a kind of majesty and personal class. Who knows why? Because there’s no reason for it. They work very well and they pose in a fantastic way – a lot of them. Soledad was a maximum of this kind of person.”

Soledad Miranda was born of Portuguese parents in the Spanish city of Seville, with gypsy ancestry, began her career as a flamenco dancer, and made her media debut in the gossip columns as the rumoured girlfriend of Spain’s leading bullfighter. All of which contribute to the image of the ultimate sultry senorita, a Hispanic femme fatale, a modern version of the operatic anti-heroine Carmen. Yet there was something more to Soledad, something fans suggest was brought out by Jess Franco in his oddball, poetic, sleazy horror films. “Once a young, dimpled, bubbly starlet, she became the pale, haunted, mysterious icon of Franco’s movies”, according to Amy Brown. “She was not beautiful”, insists the director himself. “I saw her through my lens many times and she was not beautiful. But she had a mystery.” He’s wrong by most estimation – Soledad was uncommonly beautiful – but there was something more to the actress, the enigmatic sense of dangerous sensual energy contained within her delicate physique. “She was very sentimental and very carnal at the same time”, says Jess.

“You are one of us now. The Queen of the Night will bear you up on her black wings.”

While Franco was distraught by the death of his first major muse, it did nothing to slow his cinematic output, and he would find a new muse. Lina Romay began her acting career playing the gypsy girl Esmeralda in Franco’s 1972 film The Erotic Rites of Frankenstein, a typically torrid and kinky version of the Frankenstein story, where surreal plotting and low-budget invention soon overwhelm the narrative. Franco has described Lina as “a little bit of a re-incarnation of Soledad Miranda”, though as their relationship developed – both professionally and off camera – Romay’s own distinctive qualities soon shone through. The adjective often applied to the actress is ‘uninhibited’. While Franco says Soledad Miranda had no qualms about her nude scenes, his new star appeared to positively thrive in the sweaty realms of sexual excess he created on screen. Unabashedly sexy rather than beautiful in a Hollywood sense, Lina staked her own claim to undead immortality in Female Vampire (1972), in which she plays Countess Irina von Karlstein, a mute succubus who drains her victims during oral sex, frequently wearing little more than boots, a belt and a cloak. “It’s said than I am an exhibitionist”, observes the actress. “Every actor is one – I gladly accept that. I’m not a hypocrite.”

As mainstream cinema became more sexually explicit, independent filmmakers needed to stay one step ahead, and Jess Franco’s work increasingly crossed the line between erotica and pornography. It’s a distinction the director doesn’t recognise. “What is hardcore?” he says. “What is the difference between an erotic film and a porno film? It is the point of view of the camera. So you know it’s a stupid classification. If you shoot a scene with the camera above it is erotic, but you do the same thing with close-ups… it’s porno. The intention is the same. It’s the point of view of the camera.” On a more practical level, if he wished to keep making films, Franco needed to take his funding where he could find it, and this increasingly meant making pictures that would appeal to the burgeoning ‘adult’ movie market. For Franco filmmaking is clearly a passion that borders upon compulsion. While critics might castigate his slipshod production values and gleeful disdain for good taste, nobody can seriously doubt his dedication to the medium, making movies in less time than it takes most of his Hollywood contemporaries to agree on a schedule.

After decades as a cult figure among fans of cult European horror and sexploitation cinema, Jess Franco finally received official recognition for that dedication in 2009. Accompanied by Lina Romay, now his wife, the proud director received a Goya award, which is the highest award issued by the Spanish Academy of Art and Cinematographic Sciences. Perhaps, in part, in recognition for his refusal to bow to the rules imposed by his namesake, General Franco, when other Spanish filmmakers toed the line. “I think a censor is a kind of dictator”, says the director. “The thing is so old-fashioned. They try to cut our wings. It’s a pain in the ass. I hate that. I like freedom. I have always liked freedom. I left Spain because I liked freedom.” Meanwhile, Soledad Miranda now has a street named after her in her native Seville. In a recent interview, Franco was asked which actress might play Soledad in a biopic – Kiera Knightley, Salma Hayek, Penelope Cruz perhaps? “The names you tell me now are the names of very pretty girls, with beautiful backgrounds, but not one of them got the power, the personal power, fire, to be Soledad. No one!”