I somehow felt compelled to write something on this. As, on April 11th last year, the Madam Tussauds Chamber of Horrors closed down, and nobody seemed to care. There was no fanfare, no protest, no indication in the media that I can find that this had happened at all. I have a special passion for waxwork museums (which I’ll explore in the second half of this blog) but even without that, it seemed to me that something significant at the core of our cultural heritage had died, wholly unmarked and unmourned. Some two centuries of London tradition deleted with the click of mouse from a Powerpoint presentation at some corporate marketing meeting. There was no official statement on the closure from Madam Tussauds that I could find. Just the following bald statement:

I somehow felt compelled to write something on this. As, on April 11th last year, the Madam Tussauds Chamber of Horrors closed down, and nobody seemed to care. There was no fanfare, no protest, no indication in the media that I can find that this had happened at all. I have a special passion for waxwork museums (which I’ll explore in the second half of this blog) but even without that, it seemed to me that something significant at the core of our cultural heritage had died, wholly unmarked and unmourned. Some two centuries of London tradition deleted with the click of mouse from a Powerpoint presentation at some corporate marketing meeting. There was no official statement on the closure from Madam Tussauds that I could find. Just the following bald statement:

‘The chamber closed until further notice on 11 April 2016, due to many complaints from families with young children.’

Yet they should have said something. For, whatever you may feel about the morbid character of the Chamber of Horrors, as much as a visit to Madame Tussauds Waxworks has been a must for visitors to London for generations, the Chamber represents the dark foundation of the institution, hooking it bloodily into European history. Our story begins with a French physician named Dr Philippe Curtius, who became skilled in creating wax models to illustrate anatomy. In 1765 the good doctor decided to abandon medicine and dedicate himself entirely to the art of sculpting human figures in wax. His displays were a huge success and by 1770 he had a permanent wax museum in Paris. Curtius’s Caverne des Grands Voleurs (Cavern of the Great Thieves) opened twelve years later, showing the likenesses of notorious criminals, often taken from their executed cadavers, and was similarly successful.

Yet they should have said something. For, whatever you may feel about the morbid character of the Chamber of Horrors, as much as a visit to Madame Tussauds Waxworks has been a must for visitors to London for generations, the Chamber represents the dark foundation of the institution, hooking it bloodily into European history. Our story begins with a French physician named Dr Philippe Curtius, who became skilled in creating wax models to illustrate anatomy. In 1765 the good doctor decided to abandon medicine and dedicate himself entirely to the art of sculpting human figures in wax. His displays were a huge success and by 1770 he had a permanent wax museum in Paris. Curtius’s Caverne des Grands Voleurs (Cavern of the Great Thieves) opened twelve years later, showing the likenesses of notorious criminals, often taken from their executed cadavers, and was similarly successful.

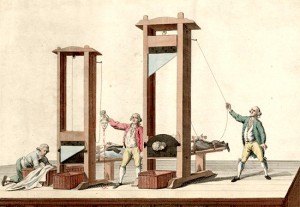

Unusually perhaps, the doctor took a young girl under his wing as his apprentice, named Marie Grosholtz, she was the daughter of his housekeeper. Marie referred to Curtius as ‘uncle’ and soon proved to be an eager, able sculptor in her own right. By 1780, their work began to enjoy approval at the highest levels of French society. They were even invited into the household of Louis XVI. But then, in 1789, history intervened in the bloodthirsty shape of the French Revolution. The next time Marie would encounter the royal family, it was as decapitated corpses. Not long after the Revolution began, her royal association had led to Marie’s arrest as a suspected Royalist. She even got as far as having her head shaved in preperation for her own appointment with the guillotine, when her skills saved her.

Unusually perhaps, the doctor took a young girl under his wing as his apprentice, named Marie Grosholtz, she was the daughter of his housekeeper. Marie referred to Curtius as ‘uncle’ and soon proved to be an eager, able sculptor in her own right. By 1780, their work began to enjoy approval at the highest levels of French society. They were even invited into the household of Louis XVI. But then, in 1789, history intervened in the bloodthirsty shape of the French Revolution. The next time Marie would encounter the royal family, it was as decapitated corpses. Not long after the Revolution began, her royal association had led to Marie’s arrest as a suspected Royalist. She even got as far as having her head shaved in preperation for her own appointment with the guillotine, when her skills saved her.

Under literal pain of death, Marie was ordered to make wax models of the heads of decapitated aristocrats – many of them former patrons and friends that she had to find for herself from among the piles of cadavers – for public display. According to one story, the originals kept rotting and falling off their appointed spikes, necessitating more durable, convincing artificial alternatives. By 1795 the worst savage excesses of the French Revolution had passed and Marie had found herself a husband, an engineer named Francois Tussaud. Dr Curtius had died the preceding year, leaving all of his wax models to his protege, and Madame Tussauds Waxworks was born (the apostrophe in Tussaud’s was abandoned some time ago). In 1802 they took the show on the road, crossing the Channel to bring their waxworks to an English audience.

Under literal pain of death, Marie was ordered to make wax models of the heads of decapitated aristocrats – many of them former patrons and friends that she had to find for herself from among the piles of cadavers – for public display. According to one story, the originals kept rotting and falling off their appointed spikes, necessitating more durable, convincing artificial alternatives. By 1795 the worst savage excesses of the French Revolution had passed and Marie had found herself a husband, an engineer named Francois Tussaud. Dr Curtius had died the preceding year, leaving all of his wax models to his protege, and Madame Tussauds Waxworks was born (the apostrophe in Tussaud’s was abandoned some time ago). In 1802 they took the show on the road, crossing the Channel to bring their waxworks to an English audience.

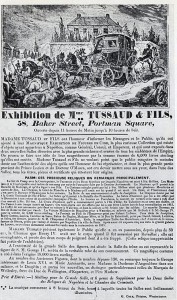

‘Her odyssey was amazing at the time, when almost no married women worked, and when travelling even a short distance was arduous,’ observed Tussaud biographer Pamela Pilbeam in an article for Business History. ‘Marie remained on the road for nearly 33 years in total, visiting 75 main towns and some smaller places. The packing and unpacking alone, without the travelling, and model and costume making, would have been herculean tasks for a young person, but Marie set out when she was already middle-aged, with a tiny child, knowing noone and speaking not a word of English when she began.’ The English exhibitions were a resounding success, but the Napoleonic Wars prevented the Tussauds from returning to France for some time. Abandoned by her husband by this point, Marie decided to relocate, finally taking up permanent residence in London’s Baker Street in 1835.

‘Her odyssey was amazing at the time, when almost no married women worked, and when travelling even a short distance was arduous,’ observed Tussaud biographer Pamela Pilbeam in an article for Business History. ‘Marie remained on the road for nearly 33 years in total, visiting 75 main towns and some smaller places. The packing and unpacking alone, without the travelling, and model and costume making, would have been herculean tasks for a young person, but Marie set out when she was already middle-aged, with a tiny child, knowing noone and speaking not a word of English when she began.’ The English exhibitions were a resounding success, but the Napoleonic Wars prevented the Tussauds from returning to France for some time. Abandoned by her husband by this point, Marie decided to relocate, finally taking up permanent residence in London’s Baker Street in 1835.

‘Exhibitions illustrating the iniquities of the Revolution were popular in Britain,’ Pamela Pilbeam, notes. ‘What made Marie’s unique was that she and Curtius had made the figures from the living, or dead, bodies of their subjects. For the first time, English audiences could really see the features of the guillotined king and queen, whose deaths they had mourned.’ Londoners could gaze upon wax figures actually cast from executed aristocrats and monarchs, figures that embodied the ethos that would drive Madame Tussauds for the best part of two centuries – a mixture of celebrity, history and morbidity. The ethos casually abandoned in the recent closure of the Chamber of Horrors…

Madame Tussauds hasn’t always had a Chamber of Horrors, even if it has always displayed horrific waxworks. Originally it was simply known as the ‘Separate Room’ in recognition that it was separated from the other less harrowing displays. Nobody was obliged to go in – which has always been the case – putting those ‘complaints from families with young children’ which led to the recent closure of the Chamber of Horrors in context. But more of that anon… There is some controversy as to when the Separate Room became the Chamber of Horrors. Some say the term was first coined in an 1845 article in the humorous magazine Punch, though others maintain Marie had been using the term herself for at least a year before then.

Regardless, the same meticulous dedication to veracity prevailed which had distinguished the grislier displays she had brought with her from the French Revolution when preparing new inhabitants for her Chamber of Horrors. Allow me to quote from my own book, SAUCY JACK, co-authored with true crime expert Paul Woods…

Regardless, the same meticulous dedication to veracity prevailed which had distinguished the grislier displays she had brought with her from the French Revolution when preparing new inhabitants for her Chamber of Horrors. Allow me to quote from my own book, SAUCY JACK, co-authored with true crime expert Paul Woods…

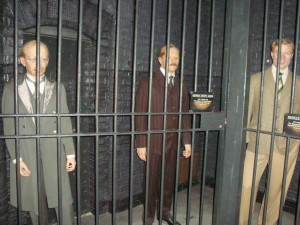

In addition to working from life wherever possible, Tussaud’s went to considerable effort and expense to obtain authentic artefacts relating to the cases they featured – from clothes actually worn by the accused to furniture or even structural elements from the scene of the crime, which would go on display alongside the completed figure.

Such attention to detail and concern for veracity not only strengthened the claims of Madame Tussaud’s to represent a museum rather than a ghoulish freak show, but also lent the Chamber of Horrors a strange, almost totemic quality – the visitor walking among the exhibits would almost literally be rubbing shoulders with killers.

The attraction was a huge success, drawing visitors as eminent as the Duke of Wellington and Queen Victoria, and the introduction of a notable new criminal to the collection was like an opening night, with queues curling out of the building to catch a chilling glance of the Chamber’s newest inmate. Not everybody was a fan. William Thackeray Makepeace fretted over the addition to the Chamber of effigies of Frederick and Maria Manning, sent to the gallows in 1849 for the murder and robbery of an elderly friend of theirs. “Should such indecent additions continue to be made to this exhibition the ‘horrors’ of the collection will surely predominate,” the author fretted. “It is painful to reflect that although there are noble and worthy characters really deserving of being immortalised in wax, these would have no chance in the scale of attention with thrice-dyed villains.”

It’s an argument that echoes to this day relating to the depiction of violence in the media. Does it inspire criminality, as some contend, or act as a cathatric safety valve? The Victorian public continued to vote with their feet and, after Madame Tussaud died in 1850, her sons Francis and Joseph expanded the Chamber of Horrors the following year to cater for the popularity of exhibits like the Mannings, displayed alongside an effigy of their victim and a scale model of the room in which he was murdered. In an attempt to stave off criticism, the Tussauds assured visitors that “so far from the exhibition of the likenesses of criminals creating a desire to imitate them, experience teaches that it has a direct tendency to the contrary.” Reliably confirming or contesting such claims has challenged generations of criminologists, psychologists and sociologists.

John George Haigh, the Acid-bath Murderer, visited Madame Tussaud’s Chamber of Horrors on the day before his arrest in 1949. Haigh subsequently became a popular exhibit, bequeathing a suit of clothes to Tussaud’s for the display. Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, is reported to have been a boyhood regular at the waxworks in Blackpool, particularly favouring a macabre anatomical display. If a visit to the Chamber of Horrors was really the first step on the road to Hell, you would expect a queue to the scaffold to mirror those that formed outside Madame Tussaud’s when a new horror was due to be unveiled. But no such symmetry has ever been observed.

John George Haigh, the Acid-bath Murderer, visited Madame Tussaud’s Chamber of Horrors on the day before his arrest in 1949. Haigh subsequently became a popular exhibit, bequeathing a suit of clothes to Tussaud’s for the display. Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, is reported to have been a boyhood regular at the waxworks in Blackpool, particularly favouring a macabre anatomical display. If a visit to the Chamber of Horrors was really the first step on the road to Hell, you would expect a queue to the scaffold to mirror those that formed outside Madame Tussaud’s when a new horror was due to be unveiled. But no such symmetry has ever been observed.

Despite this, Madame Tussaud’s descendents continued to endeavour to defend the propriety of their Chamber of Horrors. In the 1870s her grandson Joseph made a valiant effort to rename it the Chamber of Comparative Physiognomy. Physiognomy – the ancient art of determining character according to facial characteristics – was popular in the day, and if Joseph Tussaud might have legitimately claimed some scientific value to his exhibits in attempting to identify a distinctive criminal ‘look’. To make such a claim plausible, the models had to be as close to their inspiration as humanly possible.

The Chamber of Horrors seemed on safe ground when SAUCY JACK was published in 2009 – I never imagined that such a long and distinguished – albeit macabre – tradition might disappear as it did with so little ceremony last year. In 1996 the Chamber enjoyed a $1.5 million revamp, though the French Revolution death masks and John George Haigh – complete with original suit – remained unchanged. But things have changed. In 1977 Tussauds was no longer a family concern after being taken over by the Pearson corporation, the first of a series of company mergers and takeovers, that saw Madame Tussauds fall into the hands of the Merlin Entertainments company with the Tussauds Group effectively dissolved in 2007.

This may explain other developments in the Chamber of Horrors. Merlin took over London’s other major macabre tourist attraction, the London Dungeon, in 1992. Founded in 1974, the London Dungeon had originally been a traditional waxwork museum, focused on horrific historical tableaux. Under Merlin, the London Dungeon began replacing the waxworks with themed rides and live actors in period costume. Recent years saw the Chamber of Horrors following a similar policy of introducing actors to supplement the museum’s traditional inanimate exhibits. Yet none of this hinted at the decision to close the Chamber in 2016.

Perhaps, once the company owned both Tussauds and the Dungeon the business decision was simply made to focus all of their ghoulish displays in one franchise, meaning that a Chamber of Horrors in Tussauds seemed superfluous. Perhaps the Chamber of Horrors was deemed the least popular, and hence profitable, aspect of Tussauds – though the idea that our appetite for the macabre was suddenly sated after two centuries seems improbable to say the least. Sadly, it does seem most likely that the sanitising tendency of corporate culture is the most likely culprit. That a few complaints from entitled, sanctimonious parents who hadn’t even experienced the Chamber of Horrors (it was called the Separate Room for a reason – originally you had to pay extra!) were enough to trigger the corporate reflex to keep the brand’s reputation anodyne and squeaky clean at all costs.

And what’s replaced it? There are now two dozen franchised Madame Tussauds across the globe – none of which at a cursory glance feature a Chamber of Horrors. We live in a globalised world with shared values, many of which are not especially encouraging. Without access to floor-plans it’s hard to say what now occupies the space once occupied by Marie’s morbid exhibits or ponder upon the fate of John George Haigh’s suit. It doesn’t really matter I suppose. What is important perhaps is what is now considered a more compelling attraction for today’s sensation-seekers. It would seem that morbidity – and indeed history – have almost wholly given way to celebrity.

Perhaps the most horrific chamber in today’s Madame Tussauds is the Youtube display. ‘Enter into the digital world of YouTube and meet two of Britain’s most popular vloggers, Zoe Sugg (Zoella) and Alfie Deyes (PointlessBlog),’ promises the official website. ‘Step into the epicentre of the Zoe and Alfie’s “vlogsphere” and sit beside their likenesses in an exact replica of their spare bedroom, where both often vlog from. Not only were Zoe and Alfie closely involved with the creation of their wax figures and recreating their “vlogsphere”, with a donation of the Ruby Ruth Dolls that appear in the background of many of her vlogs, but so were their fans. Voting on the lipstick her wax figure would wear, as well as picking out which colour t-shirt Alfie should be dressed in – the final poll revealed that Zoe would wear Kate Moss 107 by Rimmel and Alfie a speckled grey t-shirt.’

Perhaps the most horrific chamber in today’s Madame Tussauds is the Youtube display. ‘Enter into the digital world of YouTube and meet two of Britain’s most popular vloggers, Zoe Sugg (Zoella) and Alfie Deyes (PointlessBlog),’ promises the official website. ‘Step into the epicentre of the Zoe and Alfie’s “vlogsphere” and sit beside their likenesses in an exact replica of their spare bedroom, where both often vlog from. Not only were Zoe and Alfie closely involved with the creation of their wax figures and recreating their “vlogsphere”, with a donation of the Ruby Ruth Dolls that appear in the background of many of her vlogs, but so were their fans. Voting on the lipstick her wax figure would wear, as well as picking out which colour t-shirt Alfie should be dressed in – the final poll revealed that Zoe would wear Kate Moss 107 by Rimmel and Alfie a speckled grey t-shirt.’

It would doubtless be gratuitous at this point to start any critique of the cretinous cult of pointless celebrity or indeed underline how Youtubers like Sugg and Deyes embody it. Sadly, it is the world we live in and there is no shortage of meditations on the topic. It might however be valid to pause for a moment to think about how waxworks have reflected its rise. Madame Tussauds is now a selfie facility – a temple to vacuous aspiration. Nobody went to the Chamber of Horrors wanting to pretend to rub shoulders with poisoners at fashionable parties or fancy themselves on the scaffold awaiting decapitation. So why did we go? Is our morbidity really any better than the slackjawed sycophancy feeding the Youtuber fan phenomenon? I’ll think about that in an upcoming piece.

In the meantime, I’d like to take this opportunity to raise a glass in rememberance of the Chamber of Horrors. At the very least, you deserved a more dignified wake…