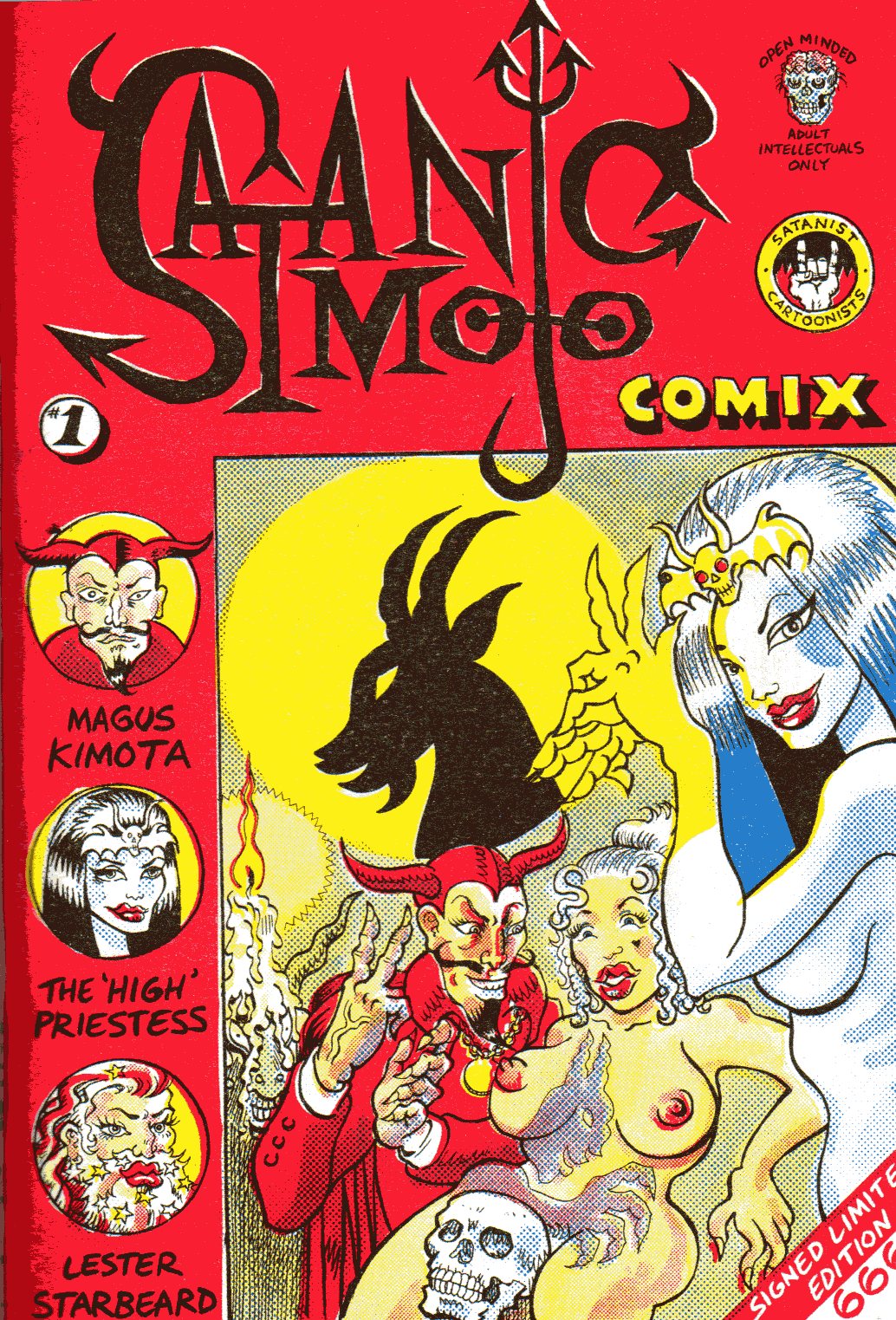

I spoke to London artist Jason Atomic some time back about matters devilish (to read our discussion click here). In particular, we talked about his upcoming art project, which had its genesis in Jason’s discovery that his name was an anagram of ‘Satanic Mojo’. The phrase conjured up images of demonic sin from the swinging 60s and sinful 70s, eras that witnessed a resurgence of media interest in the occult. By coincidence, or otherwise (Jason has mischievously suggested the influence of Crowley’s upcoming Aeon of Horus) his interest is mirrored by a burgeoning trend for occult rock in the metal scene, where bands like Ghost and Electric Wizard have tried to invoke the lost spirit of psychedelic Satanism as first conjured by the likes of Coven and Black Widow over 40 years ago.

While music has a role to play in Jason’s Satanic Mojo project, for obvious reasons, his focus has been primarily visual. At the core is a myth he has created involving ‘black acid’ and imaginary evil cults, which the artist has endeavoured to weave into authentic occult lore of the hippie era. Much of the art was then produced to try and act as faux artefacts from this fabricated episode, sinister evidence of a secret Satanic affair that never really happened. Now most of the events – the gallery shows, the Super Satanic Saturday parties – are over, the principle relic left in the wake of Mr Atomic’s affair is the Satanic Mojo Comix, and Jason was kind enough to send me a copy, asking if I’d be willing to cast my eye over it and give my considered opinion as a lifelong collector of Satanic ephemera…

The comic is a collaboration between Mr Atomic and a number of fellow travellers from the comicbook and underground art worlds, namely Shaky Kane, Garry Leach, Paul Lyons, Dennis Franklin, Matt Valentine and Josh McAlear. As this lengthy cast list suggests, Satanic Mojo Comix contains a patchwork of styles, the unifying factor being a focus on the dark side of the psychedelic aesthetic, or at least as far as the format allows, as only the cover is in colour. The spelling ‘Comix’ is significant, as (in addition to creating a little confusion over plurals and singulars) it links the comic with the underground scene that enjoyed a golden age in the hippie era, the mispelling indicating both an anarchic attitude and X-rated subject matter. The Satanic Mojo Comix certainly follows suit, with its chaotic style, explicit content and determination to thumb its collective nose at ‘the man’.

As a straightforward comic, perhaps inevitably, Satanic Mojo Comix is only a mitigated success. While the stories are undeniably fun, there just isn’t enough of it when, for a similar price you could pick up a hefty full-colour graphic novel with far more pagination, depth and sophistication. Yet such a comment misses the point. Satanic Mojo Comix is endeavouring to replicate something from long before graphic novels raised the medium to the levels of literature, to an era when graphic comics usually implied the healthy dose of sex, drugs or gore found in the quasi-illicit world of underground comix. Fifty years ago, the depiction of such adult material, particularly in a medium traditionally associated with children, raised eyebrows (among other things).

Today, when every feasible form of perversion is only ever a mouse click away, transgressive comics – even transgressive Satanic comix – inevitably struggle to outrage or arouse modern readers and critics. Yet again, it’s probably pertinent to observe that Satanic Mojo Comix is more an artistic faux artefact than a conventional comic. I’ll elaborate on that shortly, but first let’s take a quick look at the contents. The spirit of underground comix legend Robert Crumb – whose famous ‘Keep on truckin’’ is given a Crowleyan twist in a Satanic Mojo pastiche – looms largest over proceedings. His lasciviously grotesque style – branded sexist, racist and pornographic by liberal critics – is woven throughout the publication.

The first story, Sex Slaves of Satan, suggests that other prominent figure of the 60s-70s underground comix movement, Gilbert Shelton. Though only if Shelton’s most popular creations, the Furry Freak Brothers, had taken a hash leaf from Charles Manson’s book and added occultism and murder to their zany drug-fuelled lifestyles. Other influences range from references to EC’s infamous horror comics of the 1950s, to subversive sexy satires of the blandly saccharine titles published by Harvey Comics, best known for Casper the Friendly Ghost. Perhaps the boldest story in Satanic Mojo Comix is the finale, where Walt Disney characters are depicted as devil-worshipping rapists – a ballsy move when Disney’s lawyers are reputed to be more ruthless and bloodthirsty than the most fanatical evil cultists.

Here, curiously enough, we find some overlap between Jason Atomic (responsible for the Disneyland After Dark strip) and arch-Satanist Anton LaVey, for both share obsessions with the USA’s foremost dream manufacturer, though perhaps for rather different reasons. LaVey liked Disney because of his bombastic, no-nonsense approach to art and his creation of ‘total environments’ and ‘artificial companions’ in the shape of the rides at his theme parks and the robots inhabiting them, going as far as to quietly suggest that Walt was a de facto Satanist, even if he didn’t realise it. By way of contrast, Jason Atomic seems to enjoy subverting the perfect, sterile world created by Disney, taking an impish delight in marrying the happy iconography of talking animals and lovesick princesses with images of deviant sexuality and sadistic violence. It’s crude but effective stuff, though I don’t know whether LaVey would’ve found it amusing or not…

Jason Atomic has expressed sincere admiration for Anton LaVey and his work on more than one occasion, though some might interpret the first strip in Satanic Mojo Comix as a disrespectful parody of the late San Francisco sorcerer. Certainly, Magus Kimota – the Satanist leader who meets a humiliatingly sticky end in the story – looks a lot like LaVey. But, bearing in mind Jason’s enthusiasm for wordplay, and the fact that Mr Atomic also looks a bit like LaVey, then there’s surely a large element of playful self-deprecation in the strip. The question of how serious the artist takes his Satanism is clearly an issue, and some diabolists will inevitably take his irreverent tone as evidence that Atomic’s merely a hipster tourist, a latecomer apt to abandon the field when his attention span is exceeded. Maybe. But LaVey was insistent that humour was central to Satanism, and contemptuous of the pious attitudes adopted by most supposed sorcerers. For what it’s worth, I think Jason gets the delicate balancing act between vaudevillian humour, lurid shock tactics and underlying serious intent about right.

The most obvious overlap between Atomic’s Comix and Anton LaVey and his concept of Satanism is in the emphasis on the importance of nostalgia. As already noted, Jason’s Satanic Mojo project reflects a burgeoning broader cultural fascination with late-60s-early-70s occult revival Satanism, manifest most obviously in the psychedelic vanguard of current cult heavy metal. LaVey’s Church of Satan was, of course, a product of that era, but LaVey’s also written at length on the power of nostalgia. Not just from a cultural or commercial perspective, but also as something possessing untapped psychological or even occult power. So, for example, LaVey suggested that cocooning yourself in an environment totally dedicated to a past era you find appealing or invigorating can protect you from the ravages of age. His most complete theory on the subject relates to Erotic Crystalisation Inertia (or ECIs) the idea that our sense of aesthetics – particularly erotic aesthetics – becomes fixed during our adolescence. As a keen Freudian LaVey believed this affected not just your sexual tastes and proclivities, but profoundly influenced almost every aspect of your psychological profile thereafter.

In LaVey’s case, his ECI was the underbelly of late-40s-50s America, in particular as encapsulated by the film noir aesthetic of classic Hollywood crime flicks of the era. He surrounded himself in décor and artefacts resonant of the era, dressed accordingly, chose cars that dovetailed with it. As did many dedicated members of the Church of Satan, and a certain noir chic came close to a uniform among many members. Which, for a long time, I felt missed the point. The noir shitck was LaVey’s ECI. To simply emulate it, when you weren’t even born when that visual world was alive, hardly follows what LaVey was suggesting. You’re not finding your own ECI – you’re borrowing someone else’s – which is only marginally better than submitting to the blizzard of arbitrary conformist nonsense of the herd. Yet, while I still feel that to a certain extent, these days I can’t help feeling that I’ve also missed the point somewhat.

To return (briefly) to the subject in hand – Jason Atomic’s Satanic Mojo Comix – he too is focusing on an era for which he surely has no direct recollection. Alongside a building wave of fringe artists in all media, who are starting to focus on the whole psychedelic Satanism aesthetic – effectively mythologising it – including, inevitably, the foundation of the Church of Satan. Yet, while I’m sufficiently ancient to just about remember some of this era firsthand (I was born the year LaVey founded the Church of Satan) surely Jason, and most of the members of the bands endeavouring to evoke the occult underground of almost half-a-century back, have only experienced it vicariously, through films, and magazines and lurid paperbacks discovered in dusty flea markets or the further reaches of eBay. Curiously, while many associate Anton LaVey with the hippie era – his Church was established at the height of movement in its San Francisco epicentre – he was vocal in his denunciation of the Flower Children as ‘psychedelic vermin’.

Any serious study of 60s-70s Satanism inevitably leads to a reference, albeit often in a derogatory sense, to the concept of decadence. Decadence is term far more often employed than understood. It’s occasionally been credited as a philosophy in certain unfashionable circles. Philosophy or not, decadence certainly represents a more intriguing perspective on modern life than the tiresome blizzard of ‘ism’s that currently dominate much popular debate. And in my opinion Anton LaVey certainly fits into the profile of a leading 20th century decadent, though not for the crass reasons usually associated with decadence by most casual commentators. The San Francisco Satanist was certainly no choirboy, but neither was LaVey just some louche lotus-eater: He was a prominent member of the Sexual Freedom League, and open about his sexual fetishes decades before it became fashionable, but part of his contempt for the hippies stemmed from their sanctification of LSD and marijuana as liberating sacraments.

Rather, it was LaVey’s fascination with an oft-overlooked aspect of decadence that marks him, in my opinion, as a leading 20th Century decadent, specifically the virtues of artificiality. While the leading French decadent pioneer and poet Charles Baudelaire was referring to narcotics in the title of his 1860 book Les Paradis artificiels, in a broader sense decadent philosophy championed artifice and illusion over nature and reality. In effect, they preached that reality was overrated, that life as experienced was always a poor second to its reflection in dreams, art, or idealised memory. Here we return to the concept of the artistic, even mystical significance of nostalgia as the world perfected. As found in the Den of Iniquity, in LaVey’s basement where he recreated a sleazy 50s speakeasy, complete with mannequin ‘customers’. Or indeed, those, like Jason Atomic who are trying to use art to recreate a version of psychedelic Satanism more stimulating and aesthetically perfect than it ever actually was in reality. Something actually made easier if, like so many of those now conjuring dark noir or hippie environments, you’ve never experienced the original firsthand.

It is tempting here to go on to speculate on the role of nostalgia in mainstream religion. How millennia of history allow creeds to propagate the most absurd fantasies as truth with the aid of rose-tinted spectacles rendered so thick by the passage of time that no hint of truth or light can possibly penetrate their lenses. But I began this rambling missive meaning to talk about Satanic Mojo Comix, and have wandered far from my original course. But isn’t this, perhaps, an indication of the publication’s success as a work of art – that it inspires speculation and debate? If you’re curious to look further into Jason’s Satanic Mojo project, then there is more here, while those eager to lay their hands on a copy of the numbered, limited edition (666 copies of course!) comic, should click here. On which note, I shall do what I wilt, then split…