‘I don’t know how long these [vacuous modern horror films] can last. I guess they’ll go on as long as people are stupid. We used to say something in the old pictures. Now they just hold up the monsters or whatever they have and say, “Look how absolutely ridiculous they are”. It’s sad, because it implies ridicule of people who are different and don’t conform. There’s no more sympathy.’ Boris Karloff, 1959.

I received the 2011 Boris Karloff biography as a Yuletide gift, and was very happy when it finally reached the top of my ‘to read’ pile recently. Having completed it, I thought a few kindred souls might be interested in my opinion of the book. At well over 500 pages, it’s certainly a monster, but is it, as Stephen Jacobs’ subtitle suggests More than a Monster?… There have been several previous biographies of everybody’s favourite Frankenstein Monster, but Jacobs clearly aims to be definitive, achieving an enthusiastic endorsement from Boris’s daughter Sara Karloff. Yet is it possible to be too ‘definitive’?… By which I mean, in his determination to leave no stone unturned, the author is sometimes in danger of burying the reader in an avalanche of detail.

It is over 80 pages before we see hide or hair of the Monster, which may be an issue for those drawn to the book from the perspective of a horror fan (surely most of its potential readership). This wouldn’t be a problem if Jacobs was adept at turning dry fact into lively narrative, but that isn’t his strong suit. In the hands of a more novelistic scribe, Karloff’s early career, struggling to make a living treading the boards in Canadian backwaters in the early-20th Century might have made for a fascinating window into a world most of us have never even thought about. Jacobs’ strengths lie more in uncovering copious secondary sources on Karloff’s life and career, and while you do occasionally wish the author would offer a little more of his own analysis, it’s difficult to fault the thoroughness of his research, even if he might have done well to prune the detail down just a little for his subject’s early years.

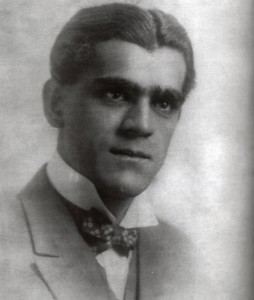

Having said which, when dealing with a subject like Boris – who was famously protective of his private life – thoroughness is a commendable quality in a biographer. So, does our author uncover any skeletons in the Karloff closet? I remember my surprise at discovering that Boris Karloff wasn’t the actor’s real name when I read Peter Underwood’s 1972 biography Karloff as a child. He was known to his family –the Pratts – as Billy, a name he concluded was not conducive to success as an actor. The former Billy Pratt further maintained that he chose his Slavic-sounding stage-name in deference to some Russian connections on his mother’s side, something Stephen Jacobs comprehensively debunks. Rather, the Pratt family had some Indian blood, which some suggest Billy was keen to conceal. Certainly, one thing that really struck me about the photographs of the young Karloff in the impressively illustrated More Than a Monster is how Indian Boris looks, something that I’d never noticed before.

It’s difficult to believe that a man as famously self-effacing and generous of spirit as Boris was racist or embarrassed about his own roots. Though it is likely that he thought that fictional roots that hinted at a past as a White Russian émigré would be more romantic in the era of the Russian Revolution than hailing from a well-to-do civil service background in the twilight years of the British Raj. If anything, it seems like Boris was embarrassed about indulging his passion for acting over following the family tradition in the civil service. Ever the Englishman, even after he became a Hollywood star, Boris remained rather apologetic about his occupation in the company of his older brothers, who had forged distinguished careers in the diplomatic corps. Indeed, the possibility presents itself that Billy Pratt changed his name not to protect his Hollywood career from his family origins, but to protect his family from the disgrace of his successful Hollywood career…

Though Karloff’s original name wasn’t a revelation, and I was aware of his Indian ancestry, the big reveal for me in More than a Monster was Boris as a young Casanova. Perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising that a humble London lad with the vim and vigour to shrug off heavy family tradition and board a boat across the Atlantic to join the theatre, should also have the romantic talents to sweep a fair few damsels off their feet. However, somehow I’d never seen Boris as a ladies man, yet even Stephen Jacobs has trouble identifying just how many official ‘Mrs Karloffs’ there were, with six as a conservative estimate. It is here, if anywhere, you might find a crack in Karloff’s halo – the slight suggestion that he might on occasion have been less than a perfect gentleman – but it is a slim and speculative chink, in a career characterised by exemplary professionalism, immense talent and truly monolithic levels of human decency.

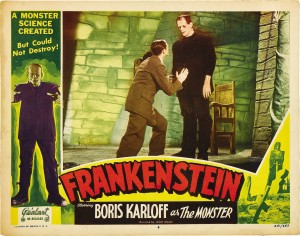

The meat of the book, inevitably, is taken up with Karloff’s career as a Hollywood star in the wake of the success of Frankenstein in 1931, though Jacobs emphasises the importance of his other endeavours. Establishing an English colony in California was a priority for Boris – he was a cricket fiend – and theatrical work, particularly in the hit play Arsenic and Old Lace and the pantomime Peter Pan, were at least as important as his film roles in the actor’s eyes. Karloff was also an influential figure in unionising Hollywood – something which, as a performer who went through some punishing ordeals in pictures like Frankenstein, was close to his heart. But, typically for Boris, it was done with grace and restraint, though the McCarthyist panics of the 50s made any such political activity risky. Karloff poured scorn on those fashionable ‘intellectuals’ who, having once been avowed Communists, upon reforming presumed to lecture others upon revising their position. At the same time, he was mystified and saddened by the way in which many Americans treated every initiative with socialist overtones as the first step on the slippery slope to Stalinist totalitarianism.

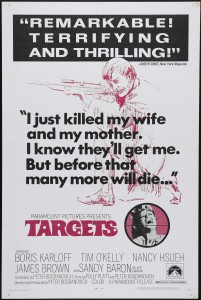

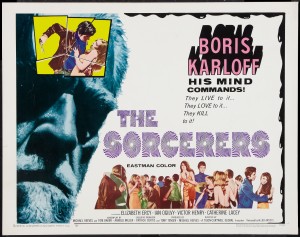

Most readers of More Than a Monster, however, will likely be most interested in Boris’s career as a horror icon. He never resented being typecast as ‘Karloff the Uncanny’ – preferring to defend the genre as being Hollywood’s version of ‘Grimm’s Fairytales’ – in contrast to his more irascible contemporary Bela Lugosi, the ill-starred Hungarian actor who fought in vain against the popular perception of him as a Gothic villain. As a consequence, Karloff worked alongside almost every significant directorial legend in the horror genre: From his career-defining performances at Universal in the 30s under directors like James Whale, to a trio of movies for RKO producer and master of sinister suggestion Val Lewton in the 40s, via appearances in Poe pictures by AIP’s king of Gothic drive-in flicks Roger Corman, to a role in The Sorcerers, a 1966 film by the troubled British director Michael Reeves. It is perhaps a shame that his performance in Targets wasn’t his swansong (Karloff made a quartet of bargain basement Mexican shockers afterwards) as it would have been a fine note to go out on.

The 1968 film, directed by Peter Bogdanovich, stars Karloff as Byron Orlok, a disillusioned horror star in his twilight years, and clearly a role with autobiographical overtones. In Targets, Orlok faces off against a young Vietnam vet (inspired by the spree killer Charles Whitman) who begins shooting innocent passersby, representative of a new, nihilistic form of terror in contrast to the gentle Gothic horror embodied by the old man. While Bogdanovich insisted that Boris was far from embittered, Karloff had expressed some reservations about the direction of the horror genre some years before. In 1959, he dismissed contemporary horror pictures as ‘cheap, tawdry and disgusting’. The timing is interesting, as he was likely referring to the success of Hammer studios, then enjoying international success, shocking the horror market back into life with The Curse of Frankenstein just two years earlier. Boris worked with Christopher Lee – who like Karloff achieved success playing the Frankenstein Monster – on Corridors of Blood in 1958. Lee recalls that, despite Boris being his usual generous and genial self on-set, discussion of their obvious connection was conspicuous by its absence…

Stephen Jacobs makes nothing of this in More than a Monster, and again, you do occasionally wish he was a little more analytical – passed the occasional comment on the material he evidently knows so well – rather than relying so heavily on quotes from other sources. But the quotes are often pure gold, as Jacobs unearths a rich seam of often amusing, occasionally poignant anecdotes featuring an irresistible cast, ranging from Lugosi and Lee, to the likes of Peter Lorre, Basil Rathbone and Vincent Price. Karloff offers little material for the biographical muckraker, but is a joy for the sympathetic biographer, and casual readers may even find the endless repetition of what a true gentleman Boris was in contrast to the roles he played slightly wearing. Yet for devotees of this inimitable performer and inspirational individual, Stephen Jacobs’ book represents an essential purchase. While falling just a whisker short of a masterpiece, it’s still a highly impressive achievement that belongs on the shelf of every aficionado of golden age Hollywood Gothic.